BRUCE TRAIL: A walk in the wilderness

The dream for the Bruce Trail along the Niagara Escarpment was born in Hamilton and almost 60 years after it was officially formed, the Dundas-based Bruce Trail Conservancy is ramping up its ambition to own the entire 900-kilometre route and a corridor of nature around it.

“Nature is not a place to visit. It is home,” said American poet and essayist Gary Snyder.

That defines the Bruce Trail and its relationship to Hamilton.

The Bruce Trail is the oldest and longest marked hiking trail in Canada, and the dream for a footpath following the Niagara Escarpment was born with a Stelco metallurgist named Ray Lowes.

The trail stretches about 900 kilometres from Queenston at the Niagara River to Tobermory on Georgian Bay. The Iroquoia section of the trail weaves its way from Grimsby to Milton, passing through Hamilton, where highlights include abundant waterfalls, Iroquoia Heights, the Dundas Valley Conservation Area, Cootes Paradise, the Radial Trail, and the Royal Botanical Gardens.

.With about 16,000 acres (roughly 6,500 hectares) of land in public ownership, the Bruce Trail Conservancy (BTC), the stewards of the trail and a natural corridor around it, is one of Canada's largest land trusts. It is headquartered in Dundas.

The BTC has a simple mission: Preserving a ribbon of wilderness, for everyone, forever.

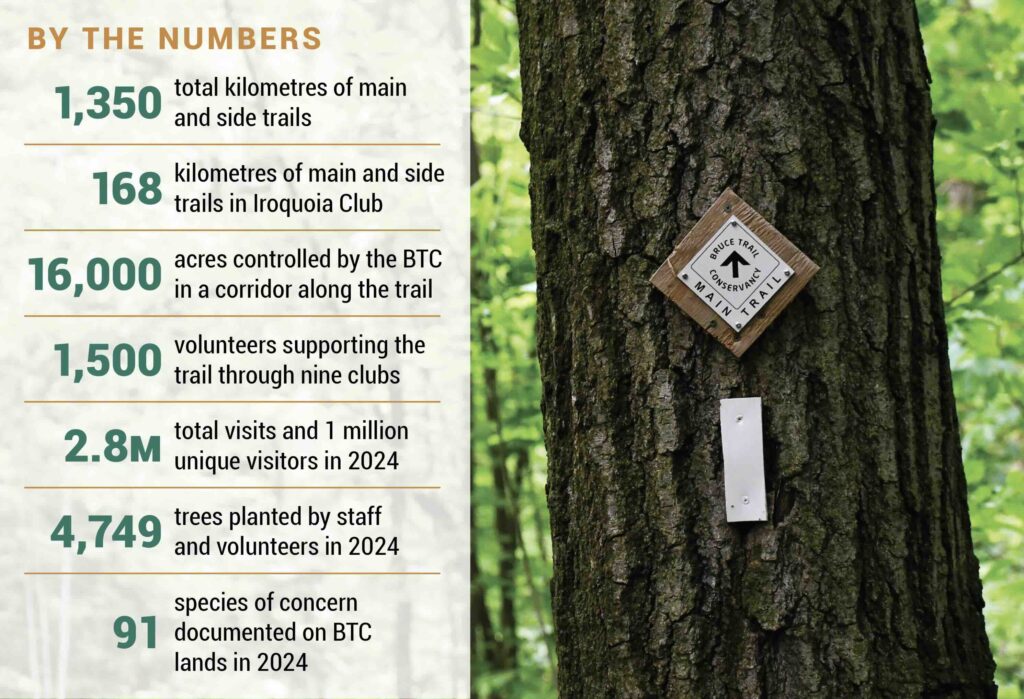

Simple does not mean easy. The Bruce Trail is more than 1,350 kilometres, including more than 450 kilometres of side trails and about 28 per cent of that is in private hands. Through a series of handshake agreements, about 623 private landowners allow the trail to run through their properties.

The BTC’s mandate to bring the entire route into public hands, for the public, is gaining momentum.

“We're incredibly unique in that we're one of the only land trusts that also facilitates public free public access to nature,” says CEO Michael McDonald. “A lot of land trusts, when they protect land it's with the intention of keeping people away. But we believe that when people are connected to places, we can get better conservation outcomes. And so our model really is unique in the land trust world.”

But securing land for the Bruce Trail is becoming more difficult due to the ever-accelerating pace of development of the Niagara Escarpment and the resulting upward pressure on land prices.

“And the truth is that we're one of the only conservation organizations in Canada that's protecting near urban nature,” says McDonald. “That's a fascinating piece of this story. We're trying to protect land in one of the most populous places in the entire country. And the Bruce Trail itself is within an hour's driving distance of over 8 million people. But this is also where all of the biodiversity is, which is why we settled here in the first place. So it's at the most risk of development but it’s also the most biodiverse. That’s why we’re working hard to protect it.”

Hamilton is the most urban place that the trail cuts through. In fact, part of the trail comes across the Jolley Cut, the heavily travelled Mountain access.

“It’s this great juxtaposition of how important the nature that we have around Hamilton really is, but also how precious it is because there's so little of it. And so when you emerge from a forest onto the Jolley Cut and then descend and walk back into the forest, I think those moments are really special for people, and sort of help translate the importance of protecting nature.”

McDonald has been in his role for six years but the Bruce Trail has been a part of his life since he was a kid growing up in Hamilton. His family would hike the local trail, especially to take in the scenic spots and waterfalls, and to look for wildlife.

“And I always remember my dad telling me, you know this trail goes all the way from Queenston to Tobermory. And I had no reference for how long that was or where those places even were, but the trail sparked an appreciation for nature and a love for wildlife and a great joy in being outside, and so that was sort of my early introduction to the Bruce Trail.”

As an adult, he was working as a manager for a marketing company and volunteering with the Bruce Trail as a hike leader and serving as president of the Iroquoia Bruce Trail Club, a volunteer position leading the Grimsby to Milton section, one of nine clubs managing the trail.

Then the CEO post came up. It is his dream job.

“I really, truthfully love this work. I feel like it's my right place in the universe. And if I'm not working or talking about the Bruce Trail, I'm out there hiking on it, and it just brings so much joy in so many ways,” says McDonald.

“It was just fascinating for me to watch people fall in love with nature. And I don't think people realize how much wildlife, how much biodiversity and how much beauty is all around us in Hamilton, but right along the length of the whole Bruce Trail.”

QUEENSTON TO TOBERMORY

Though a colonial artifact, the name of the trail comes from the beautiful Bruce (now Saugeen) Peninsula, named after a British earl. A famous book published in 1952 called the Bruce Beckons is built around the thought that the peninsula is so beautiful it calls to you. And so the Bruce Trail leads to the Bruce Peninsula.

Of course, the trail leads in two directions, with Queenston being a scenic and historic destination in its own right.

In 2024, the Bruce Trail hosted 2.8 million visits and 1 million unique visitors, says McDonald.

There are as many reasons and ways to be out on the trail as the kilometres it covers..

“The beauty of the Bruce Trail is that it can be what you want to be. For some people, it's adventure,” says McDonald. “For some people, it's spiritual. For some people, it's access to nature. But you can go for a short hike after work and walk your dog, or to walk to and from work. Or you can hike the entire Bruce Trail end-to-end as a really epic journey. And so it's beautiful in all those ways.”

‘MAGICAL AND TRANSFORMATIVE’

Some people are out there to reconnect to a childhood memory. Others are processing grief or healing from sickness or injury. Others find comfort, inspiration or spirituality in nature. Some are challenging themselves physically. Others do it for mental health.

Some are out to forage for edible plants and mushrooms, others to birdwatch or take photos.

Some do it alone and others share the experience with loved ones. For some, it’s about proving something to themselves, for others, it’s about raising money for causes like cancer research, Ronald McDonald House, ending domestic violence, and supporting veterans.

For some, it’s been a lifetime goal. Others start walking and just don’t stop. Some have completed the end-to-end dozens of times and others make it a one-and-done accomplishment.

One mother and daughter, looking for bonding time, took 20 years to travel the whole trail, breaking the span into 60 separate hikes. Two friends started hiking in their teens and finished the whole trail in their 50s.

It can also be a race against the clock.

Cornwall native Cody Taylor set the record for the fastest known time of running the 900-kilometre Bruce Trail unsupported, in just 14 days and 30 minutes in August 2024.

In 2021, Karen Holland of Kimberley, Ont., completed the trek with a support team in eight days, 22 hours and 51 minutes. For context, that’s the equivalent of completing two and a half marathons every day for almost nine days straight.

A blind runner from Barrie finished the trail in 2014, finishing the trek alongside guides in 20 days.

Through the course of the trek, hikers see caves, marshes, karsts, moraines, and waterfalls, walk through old-growth forests, and tall-grass meadows, and cross pebble beaches. They travel flat tracks, undulating hills and, of course, steep limestone cliffs.

“There is a timelessness to it,” saya Antoin Diamond, the BTC’s vice-president of land securement. “When you’re on a trail in the middle of the woods, it could be 50 years ago or it could be 100 years ago. It would have looked very much as it does now.”

Keen-eyed hikers will find rusted farm equipment, kilns, broken-down cars, dilapidated outhouses, and old stone walls that point to the history contained among the trees.

Approaching 5,000 people have certified their completion of the entire trail with the BTC. That requires submitting logs of their journey. Once verified, they receive a special badge and an official end-to-end number, and their logs are professionally archived by the Hamilton Public Library.

“So you could go and find out about your mom's or your dad's or your grandmother's hike along the Bruce Trail,” says McDonald. “And it's a really beautiful part of the story. When you think about Canada's population and the fact that this trail has been around for almost 60 years, it's a select group of people.”

The logs are fascinating, says McDonald. For some hikers, it’s a simple spreadsheet of dates, kilometres hiked, start and stop points. Others produce beautiful journals that include prose, poetry, sketches or even music.

“But the truth is, you know, tackling a Bruce Trail end-to-end is a major life adventure, and it's something that people will never forget or regret,” says McDonald, who has about 300 kilometres left in his own end-to-end. He hopes to be finished by the end of 2025.

“We're not talking about an easy walk. You're traversing up and down the escarpment, over rocks and roots and lots of climbs, and so it's, it's daunting. But again, like all adventures, you're better off at the end. It’s magical and transformative for people.”

THE BTC: REALIZING A MISSION

The Bruce Trail Conservancy, headquartered in an airy office in an industrial area of Dundas, is one of Canada’s top 100 charities, according to Charity Intelligence. The office space inspires and is inspired by the work of the BTC, featuring beautiful art, maps and photography of the trail, historical signage and artifacts, and a large boardroom with a gorgeous and massive table.

The BTC employs 26 staff and oversees the work of 1,500 volunteers who are charged with creating, protecting and maintaining this conservation corridor of roughly 16,000 acres. The trail itself represents only one per cent of that.

The expanse of the trail is approaching 72 per cent permanently protected, meaning it is owned by the BTC or a conservation authority or provincial or national park. But there are puzzle pieces missing all along the route. Over the years, private owners have donated or willed trail lands to the BTC. In other cases, the organization purchases properties as they become available.

The roughly 28 per cent of the trail that remains in private hands amounts to about 623 properties. In some areas of the Iroquoia section, where Escarpment plots are long and narrow, a landowner might own only a few metres along the trail. In rural portions, a property owner might own a few kilometres. The BTC has calculated that if all that land came up for sale today, it would cost about $109 million to buy, says McDonald.

Last December, the BTC announced that an anonymous couple has pledged to donate $15 million if the organization raises $15 million each year for the next three years for land securement. If the challenge is successful, it will raise $60 million by June 2027.

‘BOLD AND AMBITIOUS’

Land acquisitions have come in waves and have definitely ramped up again over the last decade, says Diamond. “There is a huge focus for us on trying to get this done, recognizing we've got a climate change crisis and we've got habitat destruction. It's so front and centre in people's minds. So a lot of people have jumped on board and are now carrying this vision forward.”

A realistic timeline for public control of 100 per cent of the trail corridor is 20 years, she says.

BTC board chair Leah Myers, who took on the role in January 2020, says the pandemic created a new momentum around the mission of the BTC, as people flocked to the Bruce Trail to safely exercise and get outdoors, gaining a new appreciation for the province’s green spaces. But the ability to capitalize on that was rooted in work completed several years earlier, she says.

In 2017, the board approved a new strategic plan that was about “being more bold and ambitious around realizing that vision of a fully secured trail within this conservation corridor,” says Myers. That meant boosting its land securement and fundraising activities and being more visible and vocal about its work.

“I think when I first joined the board in 2016, realization of that vision, that 100 per cent secured, felt really far off,” says Myers, whose term on the 19-member board is coming to an end.

“And we’ve got a ton of work still to do, but it feels within reach in a way that it didn’t six or seven or eight years ago. And that’s, I’m getting shivers a little bit as I say this, that’s what’s really so exciting about the time that we’re in … It feels within reach, and you feel it around the board table, and you feel it wherever you go.”

Marsha Russell, vice president of fund development, has worked for the BTC for 20 years and has also seen the scope of its ambition grow, along with the development and environmental pressures that make the work necessary.

“The people who understand that this is important and want to give their volunteer hours, their dollars, their brain power, that's also grown exponentially.”

Russell and her team of four manage the fundraising, grant proposals, land donations and bequests that will allow the BTC to protect the trail corridor.

“Forever is a really interesting, ambitious framework,” she says. “Governments are incredibly powerful, but they are the standard of the day, and they can think in cycles, whereas we, as good stewards, need to think generationally.”

Fundraising is critical, not only for land acquisitions, but for trail maintenance and conservation activities, and equipment and training for volunteers.

“One of the things that is most exceptional about our work is that public accessibility component. So there are other organizations that have a sanctuary model, where they preserve a piece of land, but either by design or geography, no one will visit. And that's not our model. We run through the most densely populated part of our province and our country, and it's also free and accessible 365 days a year. So there's this huge communal good.”

THE OPTIMUM ROUTE

The Bruce Trail’s optimum route is a line that follows as closely as possible to the edge of the Escarpment and guides all trail routing, says Adam Brylowski, manager of conservation and trail. “So every property that we acquire, the idea is that the optimum route goes through it, and so there's a good chunk of land that we want to acquire to put the trail on that doesn't have a trail on it, but it has this line.”

Each time properties are acquired, Brylowski’s team does a full ecological inventory in spring, summer and fall in order to create a land stewardship plan. That ensures a trail avoids any sensitive ecological areas and guides tree plantings, invasive species removal and wetland revitalization. From there, the plan is handed off to the volunteer land steward for that property.

Trail maintenance standards are in place that call for corridors that are five feet wide and eight feet tall. But those standards have to account for endangered or rare species. For example, butternut trees are endangered by a fungal disease and require a permit in order to be cut down. American ginseng is also highly endangered, so trails must be routed around that.

As well, there are sections of the trail that require scrambling over rocks and roots and ascending and descending steep embankments. For that reason, the Bruce Trail is categorized as a wilderness hiking trail.

“Being as close as possible to the escarpment face edge as we can (means) there are some very challenging portions of the trail, and I think that's sort of intentional, because we're just trying to follow this natural feature.”

The optimum route is revised when new development gets in the way.

“As we go forward, there are more and more problems with urban expansion and development that encroach into the natural world and impact species, whether they be animals or plants,” says Brylowski, an ecologist who has worked at the BTC for 15 years. “So the work we're doing to protect habitats and whole communities is incredibly important. In southern Ontario, the Escarpment is one of the only naturally humbling things we have to ground us and give us some perspective about the majesty of nature and where we sit in it.”

In 2024, the BTC acquired 17 properties, protected more than 942 acres, and secured over 10 kilometres of the optimum route. That included three properties in the Iroquoia section (Kilbride Pass, Birdie’s Path, and Elderberry Ridge) and preserving the last remaining vulnerable section of the Bruce Trail along Georgian Bay with the creation of the 560-acre Sunrise Shores Nature Reserve on the Saugeen (Bruce) Peninsula. Since 2021, the BTC has protected close to 2,500 acres of its wilderness corridor, removed 13.6 kilometres of trail from roads, and created or rerouted 93.5 kilometres of trail.

To combat a biodiversity crisis, the BTC undertakes ecological restoration through plantings, especially critical in wetland environments and meadows and tall grass prairie sections, which has become almost non-existent in Ontario. The organization is also commissioning a study through the Niagara Research Centre to look at the effects of climate change on species migration.

And to tackle the spread of invasive species, the BTC has partnered with gear company Baffin in Stoney Creek to build and install 100 boot brush stations to encourage hikers to clear off their boots.

THE VOLUNTEERS

The Bruce Trail has long loomed large in Peter Rumble’s life. He used to walk it to get to his classes at Mohawk College from his Durand neighbourhood apartment in the 1970s. Then he established a career in environment management, first for conservation authorities and then for the Ministry of Natural Resources.

He can now see the Bruce Trail from the veranda of his home just east of Gage Park.

Since retiring about 15 years ago, Rumble, who completed an end-to-end in 2015, has volunteered in numerous ways with the BTC. He is a trail captain, responsible for a 3.5 kilometre section of the trail through Hamilton. He’s out walking it regularly, picking up garbage, painting blazes, clearly branches and debris. Rumble is also a zone coordinator, overseeing five sections of the trail. He produces budgets, schedules major work, and coordinates volunteers for work parties to tackle projects such as bridge or broadwalk repairs.

He also serves as a trail development and maintenance director, overseeing risk management, tracking volunteer hours for 140 volunteers, and helping with grants and fundraising.

With all the hats he wears, Rumble puts in about 2.5 hours a day volunteering.

“I used to get paid for this kind of work but now I do it for free,” he says. “There is great personal satisfaction in this for me. I love to be on the trail and surrounded by trees. I think about the Indigenous folk who walked these trails before me.”

There are many volunteer roles with the BTC. They pull invasive species, help improve habitat for wildlife, and plant native species that are grown in BTC seed orchards.

About 140 trail maintenance volunteers in Iroquoia dig ditches for drainage, rebuild trail rails, staircases and bridges, stabilize slopes, paint blazes, and are trained to cut down hazardous trees.

Then there are hike leaders who plan general hikes, hiking 101 sessions, or specialized journeys for families or people looking for wildflowers or birds.

Each club has its own board of directors that all report to the BTC and every couple of years, the boards gather for a conference to talk about best practices, new ideas and common issues. Also at the club level, various committees communicate with one another every couple of months.

One of the first things Kathrin Konig learned about her new home of Burlington when she moved from Whistler, B.C. almost 21 years ago was the beauty of the Bruce Trail. Konig would take her daughter, from the time she was a toddler, on organized hikes put on by the Iroquoia club.

Konig now volunteers with the BTC, handling outreach for events and information booths. She loves talking to people about the Bruce Trail, introducing it to those who are unfamiliar with it, and sharing stories with dedicated hikers and conservationists.

“It’s been my playground for 21 years. The first picture of me on the Bruce Trail, I was eight-and-a-half months pregnant. My daughter has grown up on it.”

Konig, who is a marketing analyst at Ford Credit in Oakville, has completed the Niagara to Hamilton portion and has set a goal to hike the whole thing by December 2028 when she turns 50.

“The Bruce Trail is really a community of its own, of hikers, people who like to be outside, people who are passionate about conservation. It’s a community I’m proud to be a part of. It really fills my cup and gives me hope.”

The BTC is particularly interested in seeing newcomers, young families, and marginalized groups feel welcome to the trail, says Konig.

“We are focused on conveying the message that everyone is welcome. The trail is there for everybody to enjoy.”

THE HIKERS

Since she was a kid, Hamilton resident Amanda Rankin dreamed of one day hiking the Bruce Trail. She grew up off Locke Street and spent a lot of time at Reservoir Park alongside the trail, imagining where it led.

That first pandemic summer seemed like a perfect time to start the trek. So she set out from Niagara on July 6, 2020 with friend Tamara Cummings, who says now that she didn’t realize then she was in for all 900 kilometres.

But she carried on, the pair sharing deep conversations and occasional periods of silent reflection as they moved towards Hamilton. There, friend Shannon Kotecki, joined them. All three are elementary school teachers in Hamilton.

(To catch up, Kotecki hiked the Niagara to Hamilton portion with her daughter Cate when Cummings and Rankin took a break from hiking that first winter.)

The three reflect on their journey, which concluded on Aug. 22, 2024 after 58 days of hiking, as a cherished and special time.

“There were many times when the trail led us and showed us where we needed to learn or grow or work through something or celebrate,” says Cummings.

“You don’t get the chance to just walk and think very often. You aren’t on your phone, bells aren’t ringing all around, kids aren’t asking questions. You are 20 kilometres from the car and you just have to walk and be in the moment.”

Though Rankin carefully planned each day’s hike, the three allowed themselves to explore side trails where they led to scenic lookouts, waterfalls, caves and the highest point on the trail, as long as the trek didn’t take them more than 100 metres off the main trail. The trio relied on the BTC’s trail book and the phone app that launched in late 2021.

There were bumps, bruises and blisters. They mistakenly got off the main trail one hot day, hiking about 10 kilometres further than they needed to and running out of water. The only winter day the three hiked together saw them trudging through flooded farmers fields in high winds in McGregor Park near Owen Sound. Rankin’s feet were immediately soaked, Kotecki fell in a puddle, and Cummings was narrowly missed when a huge tree branch crashed to the ground just feet from her.

They didn’t hike in the winter again.

As they got further from home, they planned weekends of hiking to make the drive worthwhile. That became challenging to fit in around their lives as wives and mothers, family vacations, and caring for aging parents.

As they got to the Bruce Peninsula, the scenery was spectacular but the hiking was hard and slow, up and down rocky ledges on a narrow path. But there was a celebration with family and friends when they reached the Tobermory end-point cairn.

They spent five summers on the Bruce Trail.

“I miss it so much,” says Kotecki. “I feel like it’s a loss in a way. I miss the time we had together.”

Cummings says while she tagged along on Rankin’s dream, she now has the Bruce Trail in her blood. She will run two trail races this summer.

The three friends have started dreaming about the next trail, maybe the Cabot or the Camino.

Rankin says finishing the trail gave her more than she could have imagined.

“I got to do this with two amazing people and I am a better person because of the stuff we shared, the laughs we shared and what we learned.”

HISTORY: BLAZING A TRAIL

The story of the Bruce Trail really begins with a metallurgist at Stelco named Ray Lowes in 1959.

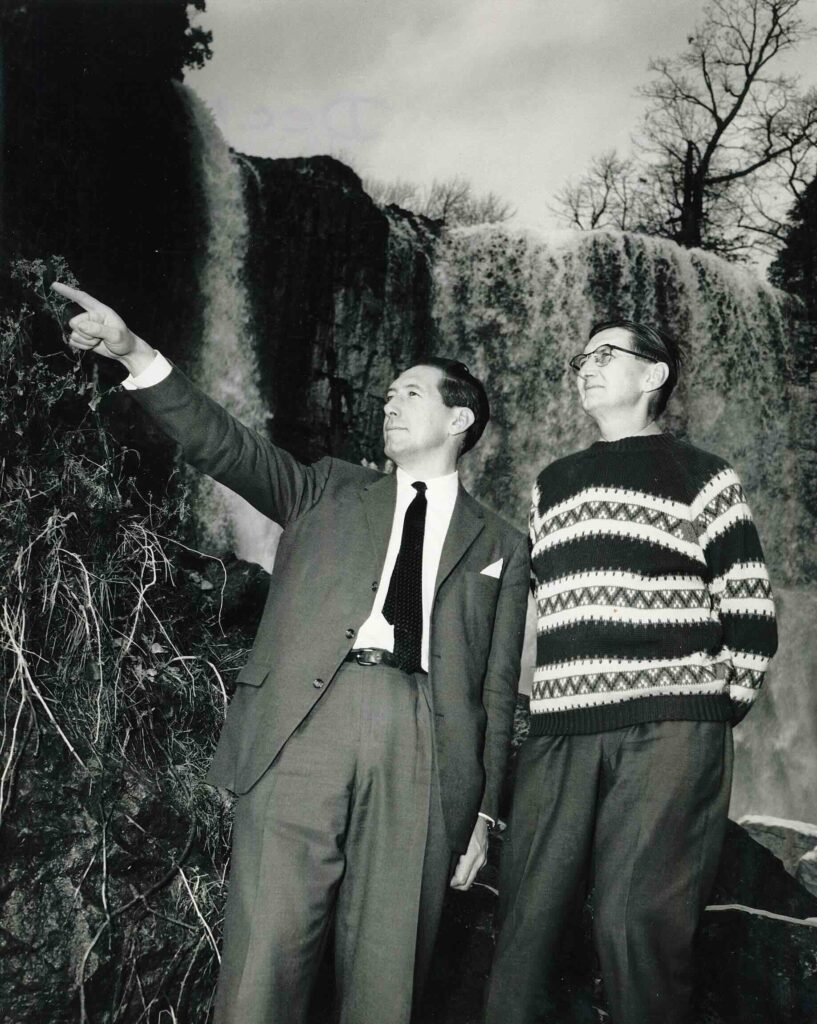

Lowes was the visionary who imagined that the Niagara Escarpment – a vital ecosystem and one of 19 UNESCO World Biosphere Reserves in Canada – could be preserved and protected from unchecked development only if people could experience its beauty and wonder first-hand through a hiking trail. He shared his idea at a meeting of the Federation of Ontario Naturalists in Hamilton and members rallied around the idea. An early ally was famed painter Robert Bateman.

In its early days, the effort was supported by Stelco and the fledgling organization operated out of the Stelco Tower in downtown Hamilton.

On Sept. 23, 1960, the first meeting of the Bruce Trail Committee took place, which in addition to Lowes, included Philip Gosling, Norman Pearson, and Dr. Robert McLaren. Gosling, who is now the sole surviving member of that founding group, was made trail director and charged with making the trail a reality.

Gosling, a former real estate and land developer in Guelph who is now in his mid-90s, took a year away from work and racked up 37,000 kilometres on his car, convincing landowners to allow access to their land and rallying volunteers to map and build the trail.

“We always say that Ray was the dreamer and Philip was the doer and Philip really helped to ignite the imagination of the public and get the Bruce Trail built,” says BTC CEO Michael McDonald.

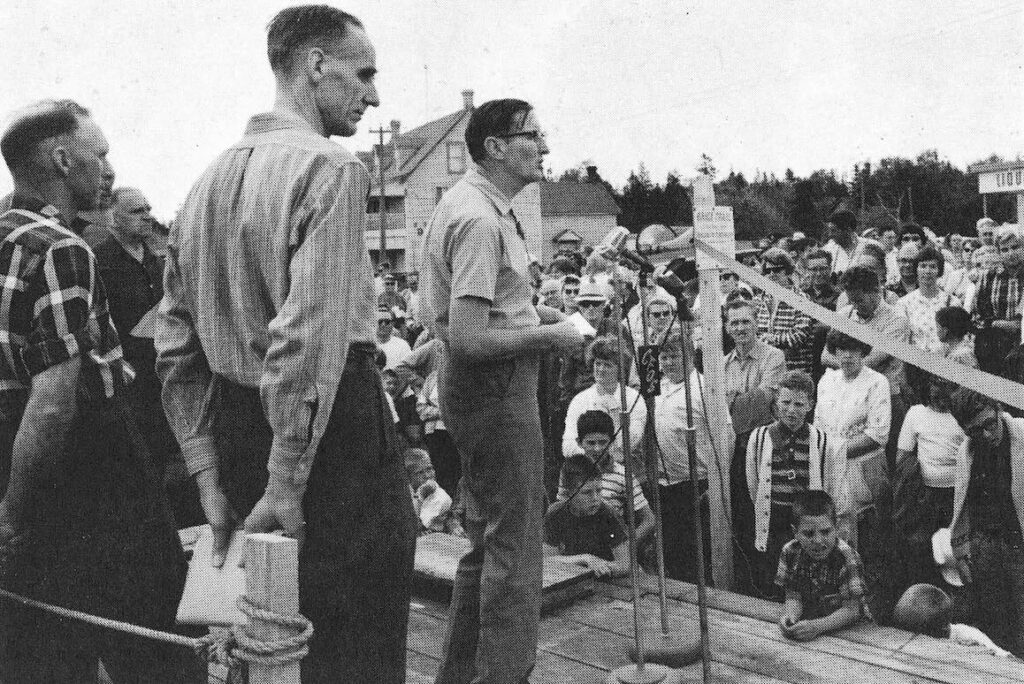

The effort got a big boost in 1962 when the Toronto Telegram newspaper sent a reporter on a pioneering hike with trail supporters from Waterdown to Craigleith.

“So in 1962 we see that's really when the Bruce Trail sort of set the imagination of the public on fire, because it was being reported on every single day about, you know the location, what they saw, what they found along the way.”

In one year, 250 kilometres of trail were marked or built. In July 1962, the first blaze was painted near Kelso, and in 1963, the Bruce Trail Association was incorporated. The Bruce Trail Conservancy was formed in 1967 and the trail was officially opened on June 10, 1967, Canada’s centennial year.

The Niagara Planning and Development Act, which established the Niagara Escarpment Plan and the Niagara Escarpment Commission to manage development and protect the area's unique ecological and scenic features, was enacted in 1973.

The Bruce Trail’s optimum route was identified in the 1980s.

In 2006, contractor Patrick McNally's donation of 27 acres of land and his home marked the largest gift in the Bruce Trail Conservancy's history. The McNally Nature Reserve near Waterdown is credited with kickstarting a new era of land acquisition for the BTC.

In 2016, the BTC moved from its 32-year home at the Royal Botanical Garden’s historic Rasberry House at the Arboretum in Dundas to a modern office building in the Head Street industrial park.

Gosling, who went on to found the Wellington Brewery, the Gosling Foundation, and the Gosling Research Institute for Plant Preservation at the University of Guelph, was named to the Order of Canada in 2013.

“The Bruce Trail was a dream that came true and is a miracle of volunteerism. I never imagined the huge response and support from the public would translate into one of the biggest conservation success stories in Canada,” Gosling wrote in his book Bruce Trail Stories: 1962-1967 Memoirs.

For this story, Gosling wrote: “I was amazed how soon Hamilton residents, excited by the prospect of building a public trail, came together to help weave a trail through parks, subdivisions and public spaces … It was a momentous time and a revelation to see how different groups came together as one community to celebrate the building of the Bruce Trail, destined to be open and free to the public for future generations to enjoy forever.”

THE WONDER OF THE NIAGARA ESCARPMENT

The Niagara Escarpment is one of the most prominent natural features in southern Ontario and widely seen as one of Canada’s natural wonders. This ridge extends 725 kilometres through southern Ontario from the Bruce Peninsula to the New York border, where the Niagara River plunges over the Escarpment at Niagara Falls. The Escarpment area includes the largest stretch of continuous forest in southern Ontario and some trees along its cliff face are over 1,500 years old. It is also a source of agricultural land.

But the Escarpment’s natural environment is under threat. It is located beside the most densely populated part of Ontario, with 31 upper, lower and single-tier municipalities along the Escarpment including the cities of Hamilton and Owen Sound. Many First Nations and Métis communities, including the Saugeen Ojibway Nation and the Six Nations of the Grand River, also have traditional and ancestral territories along the Escarpment. Population pressures are mounting, with the number of people living in the Greater Golden Horseshoe expected to grow more than 50 per cent to over 14 million by 2051.

The Escarpment’s diverse habitats are home to 300 bird species, 53 mammal species, 36 reptile and amphibian species, 90 fish species and 98 butterfly species. There are at least 70 different species at risk— plants and animals whose survival is in jeopardy—that live on the Escarpment. It also has several globally rare types of habitats, as well as eastern North America’s oldest forests.

BTC: ACHIEVEMENTS AND AMBITIONS

The BTC made its largest single acquisition of land with the purchase of more than 500 acres of the MapleCross Nature Reserve at Cape Chin in 2021. That secured 1.8 kilometres of Bruce Trail in the Bruce Peninsula.

Last summer, about 830 metres of the Bruce Trail were secured thanks to an agreement with the Dundas Valley Golf & Curling Club. The BTC finalized a purchase of 2.3 acres on the north end of the club earlier this year.

A recent acquisition of 137 acres in Caledon called the Meltwater Moraine secures 640 metres of the optimum route and removes 3.3 kilometres of the main trail from high-traffic areas of Airport Road and Escarpment Side Road. The newly protected land is home to a cluster of butternut trees, an endangered species, as well as an old house that is home to nesting barn swallows, which is also at risk.

In March, the BTC launched the Bruce Trail GeoHikes Hub, interactive digital tools that offer Bruce Trail users an accessible and innovative way of learning more about the geology of the Niagara Escarpment. Each GeoHike is a one- to three-hour non-intensive self-guided tour that highlights the significance of the local geology. GeoHikes can be used as guides while walking the trail in person, or as a virtual alternative at home or in the classroom.

Most GeoHikes include virtual 3D models that show the locations of fossils and other geological features, 360-degree photos or drone videos, slide bars with overlays of important features or geologic information, and written and audio descriptions of the geology. The program was developed in collaboration with the APGO Education Foundation and the McMaster University School of Earth, Environment & Society.

The Iroquoia club has started a Trail Angels program. Hikers can arrange a shuttle with a volunteer, who will meet you at your car, drive you to a spot to hike back from. It eliminates the need for cabs or jockeying two cars and allows hikers to return to their car at their own pace, rather than perhaps rushing back for an arranged ride.

In March 2024, the BTC announced that it was working to establish campsites all along the corridor, with the goal of supporting thru-hikes by 2030.

Unlike many other long-distance trails in North America, The Niagara Escarpment Plan (NEP) doesn’t allow camping along the Bruce Trail except for a few designated spots. Those who hike the trail in one shot, from Niagara to Tobermory, have to carefully plan their nights between those sites, B&B and cabin rentals, and nearby towns.

The vision is that the campsites would allow hikers to remain on the trail for the duration of their journey.

The NEP requires that campsites be placed at least 10 kilometres apart, away from the main trail, and away from roads and scenic points to discourage abuse by non-hikers. Sewer or electrical services can’t be provided.

"Such an area would normally consist of three to six clearings for tents, a fireplace, a water source and a latrine," the plan states.

The campsites will only be created on BTC owned land.

The BTC was a founding member of the World Trails Network in 2012, and has since paired with nine twin trail organizations to raise awareness of and support for public footpaths.

There are famous trails in the world but fabulous lesser-known ones too, like the Bibbulmun Track in Australia or the Jeju Olle Trail in South Korea.

“There are people who travel the world to walk so it's a benefit for our members who love to hike and love to travel. And people around the world learn about the Bruce Trail when they are out hiking,” says the BTC’s vice-president of operations Jackie Randle, who is chair of the World Trails Network.

The BTC has also partnered with Canoo, an app that introduces new residents and new Canadians to all that Canada offers. In 2024, 1,251 new Canadians took advantage of a free one-year membership to the BTC.

How you can help

There are plenty of volunteer roles in all nine Bruce Trail clubs, including trail maintenance, conservation, leading hikes, community engagement and outreach, and administrative help in the office.

Buy a $75 membership. Fees from about 12,500 members go directly to supporting the mission of the BTC, and you get a tax receipt, plus a quarterly magazine and reduce costs for merchandise. Members also get a vote at an annual general meeting and access to organized hikes.

Make a donation. The BTC does not get regular government funding. In the past several years it has secured some federal grants, amounting to $7.4 million over five years, but that accounts for only 8 per cent of total revenue. In other years, government funding amounted to 0.3 per cent of funding.

Sign up for the BTC newsletter to see all the good work that’s happening.

Get out on the trail, on your own or on an organized hike, and leave it better than you found it by picking up any garbage you find. And if you find a fallen tree over the trail or other safety or access concerns, use the Bruce Trail app to report it.

READ ALL ABOUT IT

The Bruce Trail has inspired several books. 100 Hikes, 100 Hikers: From Tobermorey to Kilimanjaro by Hamilton’s Andrew Camani, who was the first person to take on the trail section from Grimsby to Queenston in a day’s time.

40 Days and 40 Hikes by Caledon’s Nicola Ross, which takes readers on 40 crafted day-loops that reveal stories of the trail’s flora and fauna, geology and history.

The Trail to the Bruce, which chronicles the story of the building of the Bruce Trail, written by dedicated BTC member and long-serving volunteer David E. Tyson.

There’s even a children’s book Birthday Boots, which features twins named Molly and Max, who are going on a hike with their family for the first time along the Bruce Trail. As a gift, they each receive hiking boots for their journey.