Coming to life at McMaster University

A dynamic network of startups coming out of academic research – along with an eye-popping takeover of a homegrown success story – is fuelling Hamilton’s rise as a national biotech capital.

A $2.4-billion takeover of local startup Fusion Pharmaceuticals is showing how McMaster University and Hamilton are challenging Canada’s large cities for dominance in the fast-growing business of life sciences.

“I think we’re at a tipping point where there’s so much potential and so much incredible research,” says Fusion CEO John Valliant, the McMaster biochemistry professor who founded the company in 2017. “It’s just a matter of people taking hold of the opportunity and driving it forward.”

Earlier this year, Hamilton’s pioneering cancer drug startup announced the whopping number offered by British pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca, a company that has become a household name for its COVID vaccine.

Fusion is one of 150 startups that have spun out of McMaster’s science and engineering faculty, medical school, research institutes and research hospitals. More than 600 jobs and $550 million in investment (not including the Fusion takeover) have been generated by McMaster’s top 24 startups.

Brian Bloom, a 1998 McMaster biochemistry grad who is now CEO of biotech financing firm Bloom Burton, says the Fusion takeover could become critically important in further accelerating the local life sciences ecosystem in Hamilton.

“Instead of acquiring the company, and taking the assets and laying everyone off, which is the usual playbook, AstraZeneca publicly committed to building the infrastructure that Fusion started,” he says. “The centre of excellence that is Fusion Pharmaceuticals is going to be expanded, and that creates an enormous opportunity for Hamilton and the region.”

The life sciences include treatments and medicines, biomanufacturing, medical devices, digital health and other biotech innovations. Rapid scientific advances are creating huge opportunities in the sector for startups and later-stage companies.

“Life sciences is right up there as one of the burgeoning sectors within the city,” said Hamilton economic development director Norm Schleehahn shortly after Hamilton released a life sciences strategy in 2021. The plan aims to scale up the sector by increasing awareness and attracting investment.

McMaster Innovation Park, located on former industrial and Hamilton Spectator lands east and south of the main university campus, plays a central role in this ecosystem. By encouraging life science companies to lease space and become established at McMaster, MIP has become a crucial training ground for future biotech executives, says Bloom.

“What’s important is that those companies become anchor tenants – even if they don’t become multinationals themselves – that will staff up and grow and teach people who will become confident executives five or 10 years from now.”

Fusion has a lease from MIP for offices and manufacturing facilities, now expected to expand under AstraZeneca management. Cancer therapy company Triumvira Immunologics also has facilities at MIP. The park also includes The Forge, a shared workspace for startups; the Innovation Factory, a small business incubator; and Synapse, a consortium of the major players in Hamilton’s life science sector.

Development of MIP has not gone smoothly for McMaster. Last year, the park’s CEO, Ty Shattuck, left MIP and later filed a wrongful dismissal lawsuit, saying he was fired and accusing the university of financial mismanagement. McMaster disputes Shattuck’s allegations and says it is prepared to vigorously defend itself in court.

The MIP controversy notwithstanding, a large addition to the park is coming this year with OmniaBio Inc., a contract development and manufacturing organization established by the Centre for Commercialization of Regenerative Medicine (CCRM). CCRM is affiliated with the University of Toronto and launched with funding from the Government of Canada.

OmniaBio plans to open a $580-million biomanufacturing plant at MIP this fall for leading-edge cell and gene therapies, which will employ at least 250 people in coming years.

Hamilton is challenging the top three Canadian cities – Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver – as the leading life science hubs through McMaster’s reputation as an industry-friendly and research-intensive university.

Last year, the prestigious Times Higher Education ranking rated McMaster as the top university in the world in industry impact and first in Canada for research quality.

The university’s reputation is bolstered by its world-class research centres like the Population Health Research Institute, which carries out regular health studies with 1.5 million participants in more than 100 countries.

McMaster is “a circular ecosystem,” says Leyla Soleymani, an engineering professor who co-founded FendX Technologies, a startup developing coatings to repel bacteria and viruses. “You have a place that will support not just the companies and the research, but also the people who are educated here, have roots here and want to stay in Hamilton.”

The pandemic helped to accelerate biotech research and manufacturing at McMaster and across the country, says Soleymani, appointed last year as the university’s inaugural associate vice president for commercialization and entrepreneurship.

“It’s been a catalyst. When a pandemic hits, it’s no longer feasible to rely on imports because every country is just looking out for themselves.”

In response, last year McMaster established the Global Nexus School for Pandemic Prevention and Response, an innovation accelerator tackling pandemics and other health challenges. McMaster and Global Nexus also agreed to co-host the federally funded Canadian Pandemic Preparedness Hub in cooperation with the University of Ottawa and the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

The next phase, says Soleymani, is to bolster entrepreneurship training through a new program, the McMaster Entrepreneurship Academy, which will support fellowships for entrepreneurial professors, and provide industry mentors, innovation advisors and shared lab space for startups.

“Relying on research alone is not sufficient,” says Soleymani. “We need a robust technology translation pipeline.”

READ ABOUT SUCCESS STORIES

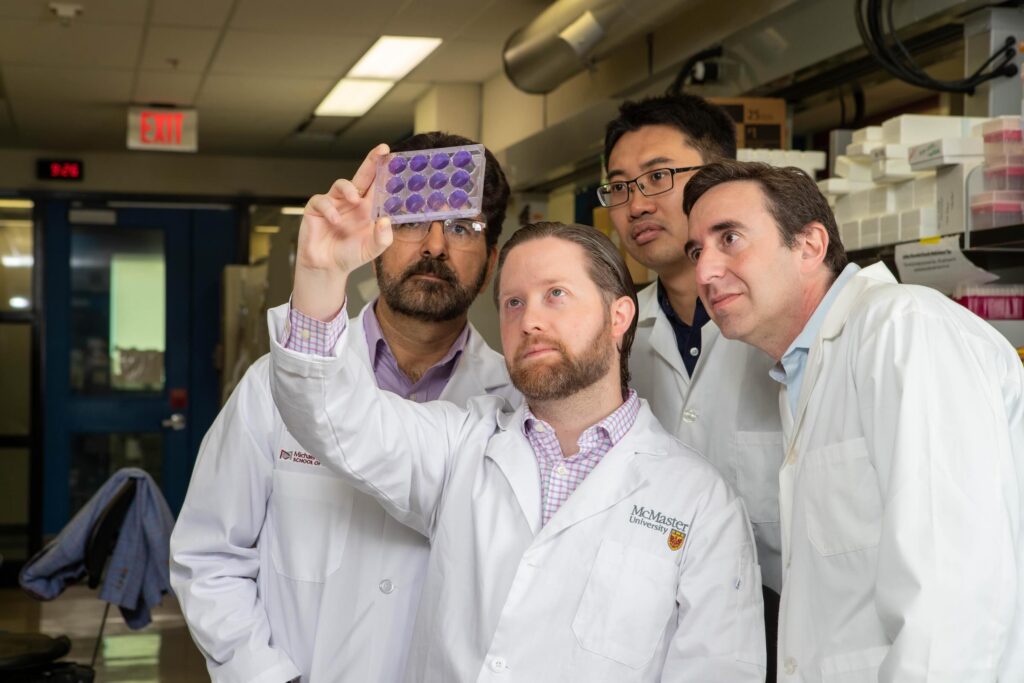

$2.4-billion takeover caps off two decades of work

John Valliant’s dream to create a “smart bomb for cancer” is becoming reality with a $2.4-billion investment by British-based drug giant AstraZeneca.

In the early 2000s, Valliant, a biochemistry professor hired a few years earlier, studied medical radioisotopes, an area of McMaster expertise since 1959 when it opened a nuclear research reactor.

He started developing the idea that radiopharmaceuticals could be “a smart bomb for cancer.” The concept was to use antibodies to carry radioactive-emitting isotopes through the bloodstream directly to cancer cells, minimizing harm to healthy cells.

The science looked promising. The tough part was moving the concept out of the lab and into hospitals and doctors’ offices.

In 2008, Valliant founded McMaster’s Centre for Probe Development and Commercialization, with the express mandate to translate radiopharmaceutical probes into commercial success. Nine years later, he founded a company, Fusion Pharmaceuticals, to bring the concept to reality.

In March, AstraZeneca and Fusion announced a takeover deal of $2.4 billion for Fusion, its patents and staff and its manufacturing facilities at the McMaster Innovation Park.

“There are a lot of people who helped us along this journey,” Valliant says. “McMaster is one, and the Faculty of Science. But there were a lot of funding agencies who supported us, and investors who stuck with us through thick and thin. This was a huge team effort.”

McMaster has also benefited from this team effort, says engineering dean John Preston.

“In the early ’90s, McMaster made a bold bet to rejuvenate its research reactor instead of shutting it down,” he tweeted on X. “A few years later, they committed to hiring a young John Valliant. Both bets have paid off nicely.”

Fighting against cancer, fighting for Hamilton

For McMaster researcher Jonathan Bramson, the struggle against cancer is waged not just in the lab, but in the university and in the wider community.

Bramson, vice dean of research in health sciences, is co-founder of Triumvira Immunologics, a cancer therapy company developing a new treatment that programs the body’s own T cells to safely attack cancer cells.

The therapy is called T cell antigen coupler, or TAC, and Bramson believes it will turn out to be a safer alternative to similar therapies that have toxic side effects.

Whether it works will be known in coming months as the company receives results from clinical trials currently underway. But getting to this stage has been a struggle.

Europe and the United States have well-developed funding systems for clinical stage companies, but Canadian drug companies have to rely on investors to support drug trials, which are very costly.

Bramson credits investment banking firm Bloom Burton – led by McMaster grad Brian Bloom – for helping Triumvira to raise more than $100 million in investment.

Startups are part of an ecosystem in which the community supports the university, and the university contributes back to the community through education and jobs, he says.

“A virtuous cycle is being created where the community has helped McMaster to thrive and McMaster is supporting the creation of these new technologies and educating the students who are needed to fill the jobs that these spinouts require.”

Bramson says he and other researchers working at McMaster are struggling to keep their technological innovations here. “Most of us who have done this in Hamilton fight to keep it in Hamilton.”

Researchers invent endometriosis test

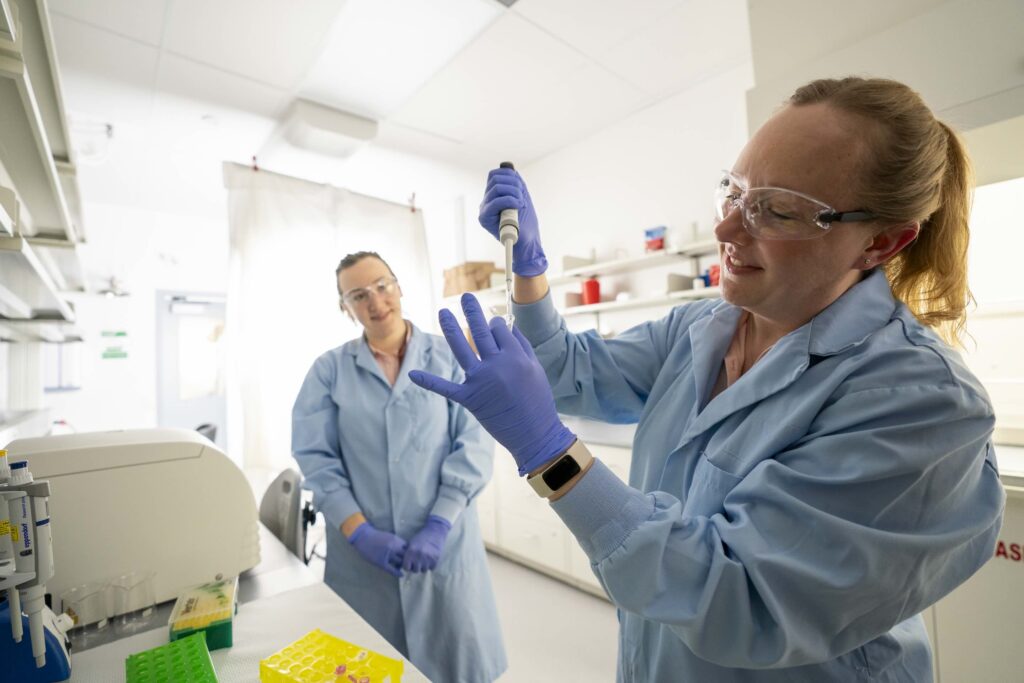

Two McMaster researchers have developed a blood test for endometriosis, a condition that often defies diagnosis and creates years of agonizing pain for millions of women.

“A woman bounces from doctor to doctor trying to get every test that can rule out other conditions,” says Jocelyn Wessels, co-founder of Afynia Laboratories, which has developed the Endomir blood test.

Wessels, who studied endometriosis as a PhD student, founded the company with Lauren Foster, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology.

It’s estimated that one in 10 women have the condition, which can create debilitating pain and infertility. The only definitive way of diagnosing it is through surgery, an option that doctors are reluctant to recommend given overcrowded conditions in hospitals. This means a typical five-to-10-year delay in treatment.

The test is part of the burgeoning field of femtech – treatments and technologies serving the needs of women and girls, which has traditionally been a niche field of medicine.

PHOTO: McMaster University

“Fifty per cent of the population is not and should not be considered ‘niche,’” says Ella Seitz, a board member of Femtech Canada, a non-profit network. Earlier this year, Afynia was one of two companies to receive a $35,000 Femtech Canada award. That’s on top of an earlier investment of $468,500 from the McMaster Seed Fund and $150,000 from the federal/provincial BioCreate fund.

Wessels started Afynia after a search for partners determined she and Foster were the best people to commercialize the test since they understand it best.

“That was almost two and half years ago and it’s been an amazing ride. I have not looked back.”

Gates Foundation backs McMaster medical startup

With the help of a $1.2-million grant from the Gates Foundation, McMaster startup Elarex Inc. is developing vaccine delivery systems that avoid the need for handling at super-cold temperatures.

While the company is still in its early stages, Elarex is aiming to develop delivery mechanisms for vaccines that are similar to breath strips or nicotine patches. Technology that could avoid the need for super-cold transportation (sometimes as low as 80ºC below zero) could have a huge impact in developing countries, says company co-founder Carlos Filipe.

“Any solution that overcomes that is going to increase vaccination campaigns around the world, making them easier and cheaper,” he says. Filipe is a chemical engineering professor recently appointed associate dean to advance research, innovation and partnership activities at McMaster’s engineering faculty.

Filipe and co-founder and CEO Robert DeWitte established the company in 2019 out of research from Filipe and his students on film and powder storage solutions for vaccines. Vaccine research is on a sharp rise at McMaster after it launched the Global Nexus School for Pandemic Prevention and Response last year.

The Gates Foundation, established by Microsoft billionaire Bill Gates, awarded the grant to Elarex in 2021 after the company received seed funding from federal research agencies and private investors.

Filipe says Elarex has benefited from a growing collaboration between McMaster’s medical school, teaching and research hospitals, and its engineering professors.

“The interaction between health sciences and engineering is becoming much tighter and people are competing for grants together. I think the stars are aligned to really have an impact.”

Assistive device becomes a passion project

In five short years, 24-year-old biomedical engineering student Lianna Genovese has used her MacGyver-like skills to transform a unique medical assistive device built in her basement into a company valued at more than $6 million.

Genovese’s accomplishment has earned her a place in last year’s Forbes Magazine Toronto 30 Under 30 list, a collection of 30 young entrepreneurial leaders in the Toronto region.

Genovese’s Guided Hands apparatus is an assistive device that enables people with limited fine motor skills to write, paint, draw and access technology like touchscreen devices and keyboards.

PHOTO: McMaster University

She was inspired to create the device after she and her classmates were introduced to Elissa, a woman who was losing hand function because of a rare form of cerebral palsy. Genovese worked with Elissa on an initial version, and built additional prototypes using 3D printers in her home basement while completing her studies.

“I built our first 25 on my ping pong table, and I shipped them across Canada to people with spinal cord injuries,” she says. “With each iteration, I tested with a person with a disability to make sure I was designing for them.”

Her company ImaginAble now ships Guided Hands to clients across Canada, the U.S. and 15 other countries. The next step is to raise investment for additional sales and new applications, including reducing the effects of hand tremors for people with Parkinson’s disease.

She says she still remembers Elissa using Guided Hands for the first time to create a picture.

“As soon as I saw her paint, I knew I had to help others like her. That’s where my project ended up turning into a passion project.”

Eugene Ellmen writes on sustainable business and finance. He lives in Hamilton.