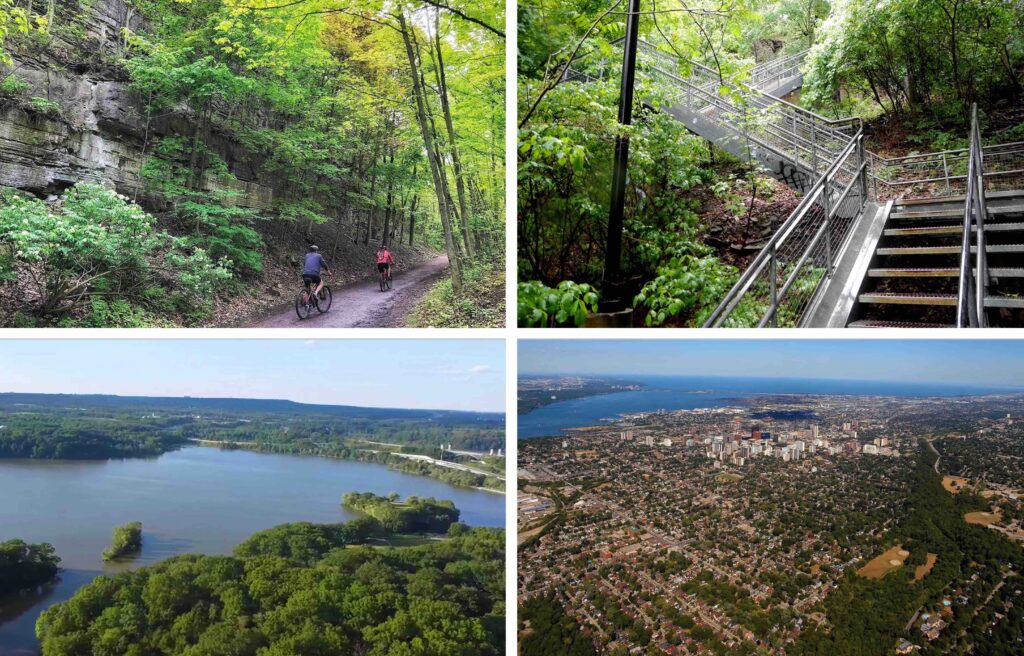

Embracing our own natural wonder

The Niagara Escarpment is a World Biosphere running right through the centre of our city. It’s a critical part of the civic identity and recreational and cultural life of Hamilton. We should be protecting and celebrating it much better than we have.

It is probably our biggest asset, yet it’s a virtual afterthought when it comes to thinking about the city’s present and future. From the Dundas Valley, to Red Hill, to Cootes Paradise, other cities would be lucky to have Hamilton’s “natural architecture,” its geological features or natural setting, but where does it register on a list of the city’s strategic assets or priorities?

Central to this architecture, both literally and figuratively, is the Niagara Escarpment. It’s so embedded in civic life that we take it for granted. The view of the lower city and the expansive vista from east to west is a common experience for Hamiltonians, whether driving or walking. Thousands move across it every day. Residents orient themselves with it – “the Mountain” to the south, harbour to the north. We have a whole series of roads with the prefix “upper” because of it. It’s so fundamental to daily life, perhaps we don’t fully realize the treasure we have.

However, it is well past time that we fully embrace the potential of the escarpment, especially in decisions that will impact the quality of life of our community over the coming years. The escarpment is connected to issues of urban sustainability, climate change, air quality, tourism, and economic development.

First, why is this landmark so significant? The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has designated the Niagara Escarpment a World Biosphere Reserve. Biosphere reserves are internationally designated protected areas that are meant to demonstrate a balanced relationship between people and nature. They are learning areas for sustainable development under diverse ecological, social and economic contexts.

There are a limited number of reserves around the globe that belong to the World Network of Biosphere Reserves. In Canada, there are 19 of these reserves, including Clayoquot Sound on the West Coast and Fundy on the East Coast. While the Niagara Escarpment runs from Niagara to Tobermory, what is unique about this biosphere reserve is that it is one of the few that travels directly through the centre of a major Canadian city: Hamilton.

The escarpment isn’t a place that we travel to, it is part of the natural architecture of the city itself. To some extent, we have embraced its value as an amenity with City parks on the brow and a network of trails along the escarpment itself. In any provincial or national park, this is common, but in Hamilton, this exists in the centre of a city, within a few steps of vibrant neighbourhoods and thousands of residents.

However, we have only begun to scratch the surface of what we could do if we fully embraced this natural asset. As a starting point, as we plan for future growth within our current urban boundary, we need to ensure our World Biosphere Reserve is front and centre. This includes elements like enhancing sustainable access as a place for urban greenspace as well as the protection of waterways that flow over the escarpment to the lake below, such as Chedoke Creek. Everyone loves the waterfalls, so let’s protect the landscape that creates them.

Similar to outstanding historic building architecture, new development should seek to be complementary with the old, without simply destroying existing landscapes in the name of progress. Part of this is protecting some views to and from the escarpment and ensuring that vertical sprawl doesn’t crowd out this treasure. This is not dissimilar to other progressive global cities, such as Montreal, that find ways to be compatible with local geological features and aim to protect their presence.

From an air quality perspective, the escarpment is home to an extensive tree canopy, which acts as a giant air filter for the city, so canopy preservation, maintenance, replanting, and expansion should be a priority. Again, this natural asset is mere steps away from thousands of Hamiltonians in several neighbourhoods so the impacts to health, both physical and mental, are significant.

Additionally, the consequences of not protecting the escarpment go way beyond recreational greenspace and beautiful views. The same elevation difference that gives us expansive vistas is also the reason why we have flooding in the lower city. In fact, mitigating the impacts of climate change is another reason we should learn to grow sustainably within our boundaries, with our biosphere reserve at the heart of our city.

From a tourism perspective, the potential of the escarpment as a destination is massive. While there are some parks with vistas of the lower city, we can do so much more while still ensuring that preservation of the natural environment is protected from increased tourist activity. First of all, how many people even know that a World Biosphere Reserve runs through the centre of Hamilton? This could be the basis for an entire tourism campaign that directly challenges outdated notions of the city.

Secondly, how can the escarpment become more of a destination? Already, thousands of Hamiltonians use the network of stairs that traverse the Mountain each day, but a look to our past as well as the example of other cities, offer additional ideas.

Some cities have embraced their elevation difference as a means to offer a unique transportation experience. Hamilton’s American steel city cousin Pittsburgh still has an incline railway similar to what was found in Hamilton a century ago. Portland, Ore. has a cable tram that offers unique views of the city while connecting upper and lower neighbourhoods.

These ideas are not as far-fetched as you might think. In fact, the 2007 Hamilton Transportation Master Plan suggested that “An inclined railway or similar facility for pedestrians and cyclists in the vicinity of Wentworth Street and Concession Street, has the potential to generate the most excitement. If carefully planned, this inclined railway could encourage cross-escarpment walking and cycling, stimulate tourism, and recapture part of Hamilton’s past.”

Just imagine a ride to the top of the escarpment to a restaurant offering a patio with views of the entire lower city. How many major cities in Canada could offer this experience? The entire view from the brow is something uniquely Hamilton: The sight of downtown, the harbour, the Skyway bridge, Lake Ontario in the distance, not to mention the panoramic view from Dundas to Stoney Creek.

The potential to create a destination experience on the escarpment brow is not new. Over 100 years ago, the Summers Stock Theatre Company was located at the top of the Wentworth Street incline railway. The 700-seat theatre officially opened in May 1902 and crowds of 73,000 patrons ascended the incline railway each summer to attend the theatre. For 11 seasons, this one-of-a-kind attraction turned the Mountain brow into a “theatre district,” until the theatre burned down in 1914. With the success of events like Supercrawl or Festival of Friends, it’s not too hard to imagine a modern-day music or theatre festival on the brow reviving this unique experience.

Balancing environmental protection with any development that makes the escarpment more of a destination will be key. However, it’s a challenge worth embracing. For too long, our World Biosphere Reserve has been an afterthought in terms of maintenance, investment, and overall recognition. It’s time to make our natural architecture a more fundamental part of how we plan our city moving forward. n

Paul Shaker is a Hamilton-based urban planner and principal with Civicplan.