Embracing the water

The CN rail yard on the west harbour has to move in order to realize Hamilton’s full potential as a true waterfront city.

Hamilton is a city on water. The harbour has been a source of commerce and recreation for the entire life of the community, and it’s what gave all inhabitants, over centuries, reason to live here. Along with the Niagara Escarpment, it is the major defining geographic and geological feature of the area.

So how come we don’t think of ourselves as a waterfront city in the same way, for example, as Halifax or Vancouver? What is the difference? Sure, the size of the body of water we sit upon is significantly smaller than the two oceans, but it has more to do with the connection between the city and the water’s edge that makes a difference.

In other waterfront cities in Canada and around the world, the link is both immediately physical as well as visual. In Hamilton, we have made great progress on waterfront development in parts, but the link to the city remains as something that happens for particular neighbourhoods in the city, rather than symbolically for the city as a whole.

This is all about proximity between the downtown core and the shoreline. Simply put, they need to be linked closer together. This wasn’t always this case as early city-building was nearer to the water and settlers moved the city centre away from the water’s edge to the area around Gore Park. In the intervening years, industry set up shop, creating a barrier between the city and water. It’s only been relatively recently, since the 1990s and the establishment of Bayfront Park, that residents have had the opportunity to reclaim some of that land from industry. Since then, development of Pier 8 has expanded this link to water further. This is all fantastic progress. However, this current epicentre of waterfront renewal is still some distance from downtown.

The area we really need to focus on, the missing link that would make Hamilton a waterfront city, is further to the west. It’s the area which is currently occupied by an expansive 13-hectare CN train shunting yard. At that location, the distance is only about a 1 kilometre to the edge of downtown. Combine this with the fact that several city blocks to the south of the CN yard are currently publicly owned, and this translates into an unparalleled opportunity to transform the identity and feel of Hamilton, reconnecting us to our roots as a waterfront city.

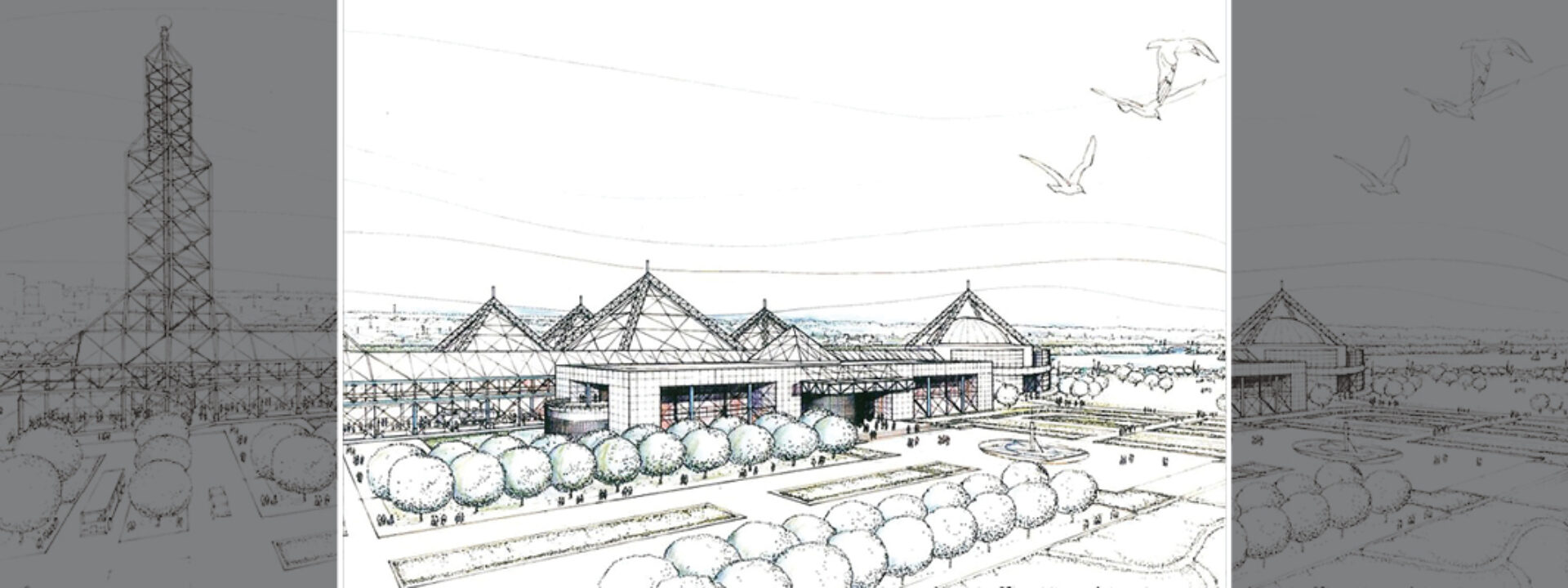

Efforts to achieve this link are not new and there have been ambitious attempts to redevelop the west harbour over the decades to make a major statement about the city. This includes the original plans by John Lyle for the High-Level Bridge over the Desjardins Canal in 1928, linking Cootes Paradise to Hamilton Harbour. Inspired by the City Beautiful movement, the original design was grand and breathtaking, creating a major water entranceway to the city. While the Great Depression downsized the plans to what we see today, ambition on the waterfront persisted.

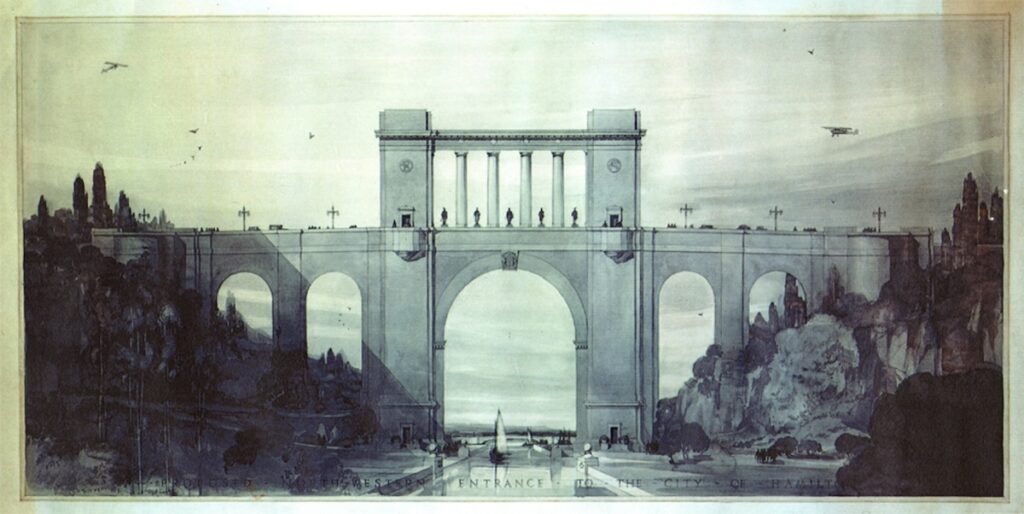

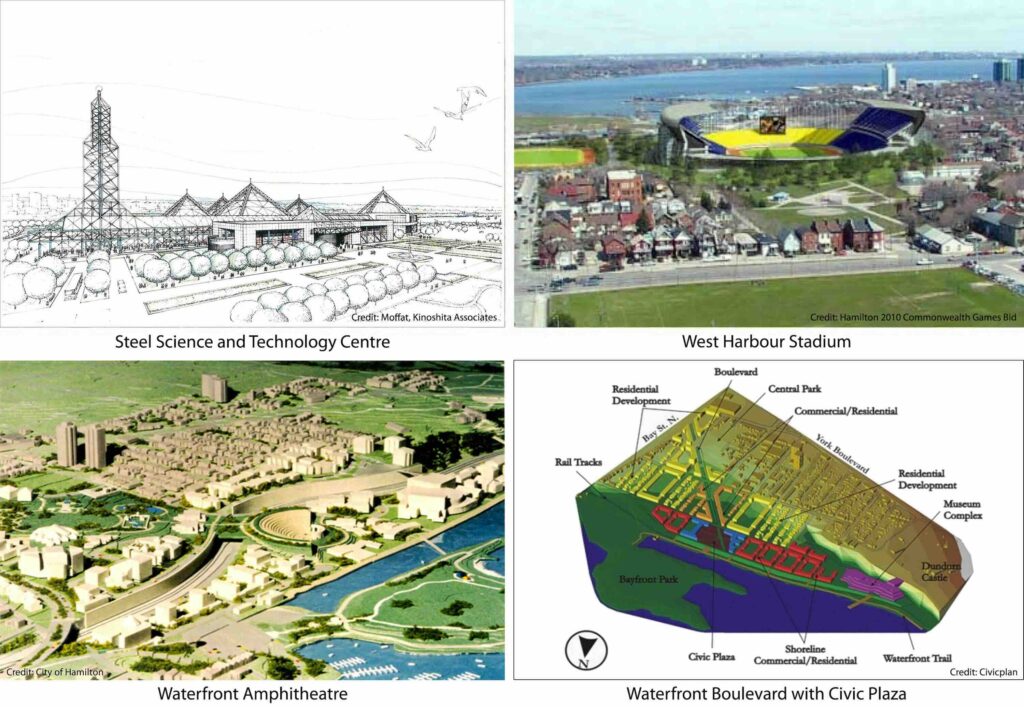

In 1985, a waterfront master plan looked to create a waterfront trail as well as establish a “Hamilton Island” with a mixture of commercial and recreational uses. In 1989, there were plans for a major waterfront museum, the Steel Science and Technology Centre, celebrating Hamilton’s industrial history, which included a Crystal Palace-style structure and IMAX theatre.

In 1995, a west harbourfront study proposed a major mixed-use development for this area, that would have seen residential and commercial zones mixed with a major tourist attraction and a large waterfront amphitheatre. One can imagine the view as residents attended a concert with the waterfront as a backdrop. Part of this plan involved the relocation of the CN rail yard and a feasibility study was produced where this was costed out. Regrettably, negotiations to implement the relocation did not progress.

Fast forward a decade and plans for a waterfront sports zone featuring a stadium were proposed, first for the 2010 Commonwealth games, and then for the 2015 Pan Am games. Once again, this could have created a link between downtown, James Street North, the new West Harbour GO Station, and the water’s edge. There was a very popular and robust citizen-led campaign, called Our City Our Future, that sought to see this vision realized. Unfortunately, that opportunity stalled due to a number of factors, but looking at all the waterfront stadia around the world, you can only wonder what might have been in Hamilton. One positive outcome from that episode is the legacy of those city blocks in public ownership.

More recently, plans developed for this area included a movie studio district, residential development and a mixed-use zone. Studies have been produced from a variety of sources including public, private and third-party groups. All these different plans present ideas of how to better connect downtown to the waterfront. For example, through the use of parks and boulevards, some plans shortened the distance between downtown and the waterfront and forged a stronger visual connection. Certain plans tried to coexist with the CN yard, while others understood the need to move it to connect the urban fabric to the water’s edge.

Currently, in the midst of an affordable housing crisis, the City is building a 40-unit temporary tiny shelter community on the site that was assembled for the stadium. This is proposed as a three-year project and perhaps a permanent affordable housing solution can be part of the redevelopment of this area.

Moving forward, now that we are in 2025 with the urgent need for urban redevelopment and intensification to grow more sustainably, it is well past time that this CN yard move. Scan waterfront cities around the world and these sorts of facilities are moved to more appropriate locations, usually to the financial benefit of the rail operators themselves who see the real estate potential of the land. This is no different for Hamilton and it’s time to dust off that relocation plan from the past. There just happens to be a large amount of industrial waterfront land to the east that might be a perfect location for such a facility.

With that barrier moved, we can then focus on completing the missing link between the city and the harbour and finally realize Hamilton’s transformation to a waterfront city.

Paul Shaker is a Hamilton-based urban planner and principal with Civicplan.