Finding a way forward after homelessness

Wayside House offers residential addiction treatment and supportive housing programs to men and male youth who are seeking sobriety. One of many success stories, Matt is finding new purpose after drug dependency and life on the streets.

In this story, we follow up with Matt, whom we met in a previous HCM article, Focusing on Humanity, published a year ago. Matt left the streets to start his recovery process and that journey included Wayside House of Hamilton, a not-for-profit organization providing residential addiction treatment to men, an area of rapidly growing need.

It looks like one of many homes in the downtown Hamilton area: old brick darkened by age, tall and solid. With four bay windows surrounding four white columns, its entrance is wide and welcoming.

Wayside House of Hamilton (Wayside) is much more than its structure. What's inside makes it unique in all of Ontario. It offers ongoing, continual support for those who are recovering from addiction. In its way, it also offers a family.

Men from all walks of life come together under one roof for their common purpose of overcoming their addictions.

“At Wayside, we have guys who are homeless, we have lawyers, we have professional people, we have dads, and they come in from across the province,” says Regan Anderson, CEO of Wayside. “Once they come here, everybody is the same.”

Since 1967, Wayside has been offering hope to men struggling with addiction. A farm boy from Norfolk County, Anderson began working in addiction services in the 1980s. He obtained his master of clinical psychology in the U.S. but, upon returning to Canada, settled in Hamilton when he joined Wayside 25 years ago.

The program at Wayside focuses on the individual, tailoring a recovery plan that has the best chance of success. The recovery process requires taking a multitude of steps, assistance from community agencies and readiness to change.

“Our goal in the program is to pick up a client where he’s at, stabilize him, give him all the information he needs, and trust – (they) respect us because we respect them,” he says. “When it comes to identifying the barriers, if it’s psychiatric, we may want to work with St. Joe’s.”

If there are physical health needs or housing needs, those are addressed, too.

“Everything we do is from a trauma-informed lens. We’re making sure this is a safe environment for people to land, catch their breath, with the skills to maintain their goal. We see some folks who may be struggling on the streets or encampments who need an opportunity to be assessed properly.”

Matt’s story

Matt lived on the streets for 25 years. He struggled with his health as a child, but it was when he was a teenager that he became addicted to opiates.

“My appendix ruptured in my teens, and they gave me tons of painkillers then abruptly cut me off,” he says. “That’s basically when I went into my high school library and researched why I felt so shitty and found out it was dope sickness. From then it was on and off finding bits of painkillers here or there. Eventually your tolerance gets strong, so you move to heroin and then when heroin was replaced with fentanyl, I went to fentanyl.”

He called himself a functional addict. When he was in his 20s, he got a high-paying executive job in Toronto. But, when he lost his job due to company closures, his addiction eventually left him on the streets in Toronto before he returned home to the streets of Hamilton. It’s harder than one may think to get off the streets, he says.

“Dehydration and regulating your body temperature is extremely hard,” explains Matt about living on the streets. “You’re either always hot or always cold and frequently dehydrated so you don’t feel very good pretty much all the time. The other thing that’s incredibly hard is you’re constantly being robbed of your belongings. If there’s anything to help the homeless epidemic, it would be getting people a place where they can store some of their belongings, even as a temporary stop-gap measure. When you’re constantly losing your belongings, even if you have the courage and opportunity to get your act together, it’s impossible because you’re constantly in a vicious cycle of not being able to get enough clothing to apply for a job or apartment or to hang onto a cell phone so you can make and receive calls,” he says.

“Then mental health issues get exacerbated because you don’t sleep. People don’t generally rob you when you’re awake. Fentanyl and crystal meth are still abundant on the street and eventually those are the two drugs just about everybody gets led to at some point because crystal meth keeps you awake and fentanyl (helps you) to forget the situation you’re in and to not feel the pain and stress of it.”

Matt was portrayed in a Human Beings of Hamilton (HBOH) post in May 2023, accepting a tent and sleeping bags for himself and his spouse at the time. HBOH shares portrait photographs and stories of the backstories of those living on the streets on Facebook, while collecting and distributing items to make that life easier.

It was around that time that Matt decided he needed to change.

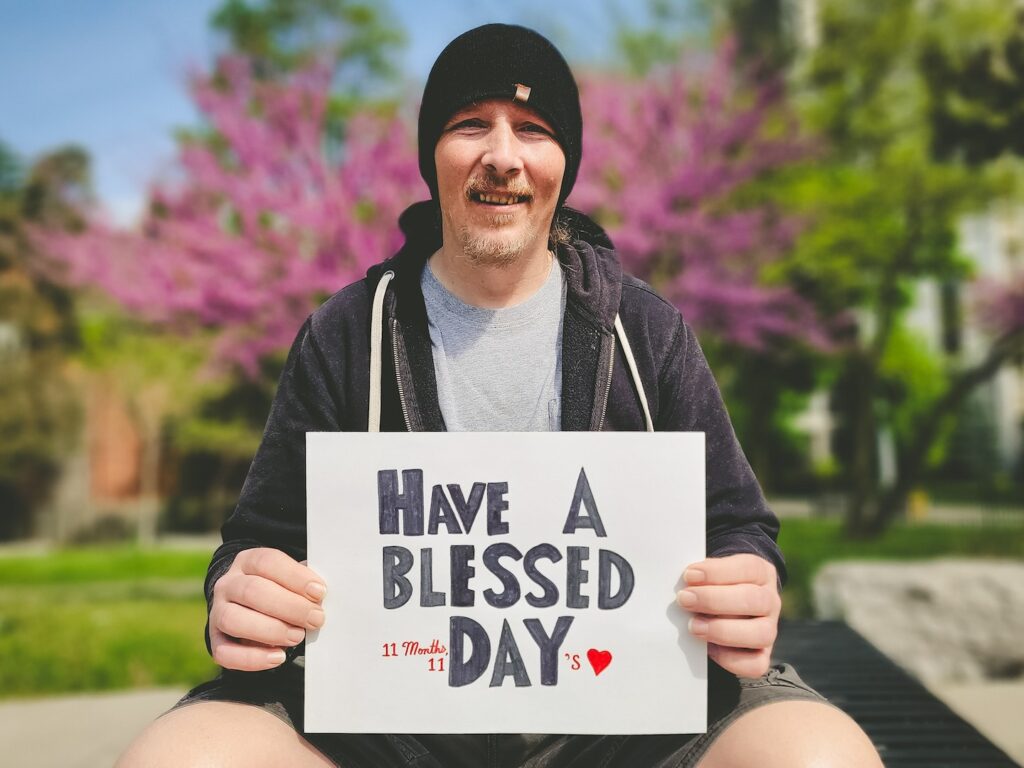

“It was shortly after Jack (Soule of HBOH) gave the tent to me and my spouse, I started to get sick of repetitively feeling like crap and having to panhandle to make money. I never committed crimes to support my habit. I just had a big sign that said have a blessed day or I had another sign that said have the best day ever but eventually I got sick of being sick all the time.”

He decided to withdraw from drug use on his own and immediately fell ill. He made his way to a hospital then stayed in detox for longer than usual.

“They actually made a special exception for me because they saw I really wanted to get sober and it takes longer than a few days to get into a rehab facility. Sometimes it can take months or even a year, so I stayed at the detox for about six weeks. I'm not exaggerating when I say fentanyl is such a strong opiate that it's not like a few days (to recover).”

A counsellor at the detox centre used to work at Wayside and put in a good word as Matt’s determination to get sober was obvious to many.

“One of the biggest things about Wayside is the sense of community,” says Matt. “It’s the community that will help you to get sober and stay sober. You have the sense of community with the staff as well, so it makes you feel needed and wanted to be part of that community. What separates Wayside from other facilities is they prove to you that they're serious with their lifetime aftercare. At anytime I can go to Wayside and have a bed for the night because I graduated from the program. It would simply take me making a call. They even pay for a cab for me to go there if I said I was worried about relapsing. So they really do focus on community as a solution.”

Currently, Matt is living in sober housing provided by Wayside. He is stronger in every way. Now, he gives back to his community, on the streets and off, while mending family relationships. He is even planning to return to school to become a social worker. Matt rightly credits himself for the fortitude to get sober, but he also credits his mother, as well as the counsellor at detox.

“If I had to pinpoint somebody besides myself, I would say it's my mom who gave support when I needed it. When you’re ready, you have to jump on it right away. When somebody has the willpower to go through that painful process, it has to happen immediately, not like the next day or the next week, it has to happen when somebody is actually willing and ready to do it because it's a really hard thing to psych yourself up to do.”

Wayside: A place of hope

For 57 years, Wayside has been helping men through their addictions. Often, men return the favour by volunteering their time to help with programs or cook in the kitchen. Matt goes regularly to Wayside to cook meals.

Ryan Kitchen is program manager at Wayside. Growing up in Brantford, Kitchen said his panic attacks as a teenager led him to develop an addiction to alcohol. It eventually affected his physical health, forcing him into recovery.

“(I have an) intense understanding of how to deal with things not going your way,” says Kitchen. “My approach to recovery is one of mental, emotional, physical, spiritual health, and developing and living a life where you’re whole. Obviously, it'll never be perfect but you're confident in your ability and feel like you have all the tools and all the skills necessary within you to be able to cope with the inevitable reality.”

Kitchen has been with Wayside for 13 years and has watched countless men recover.

“You learn things as a man, such as don't talk about your feelings, don't ask for help. All of those ideas are completely contradictory to what you need to do in order to be well,” he says. “We try to help these guys understand he may have added disadvantage purely (due to) certain man rules that he's grown up with.”

Wayside’s philosophy of a continuum of care takes into account all types of human behaviour, including relapse.

“If he feels that he’s unsuccessful, such as he relapses later, I’m not to judge him,” says Anderson. “Same way I’m not going to judge my mother who had breast cancer. She went for treatment, then the growth is back, so she had a relapse. With her, we don’t blame the person because the cancer has come back. Why would you do that with addiction? Addiction and mental health are the same as any other form of health. We just label them differently. We’ll say the guy who’s using fentanyl in an encampment is doing so because he lacks so-and-so and he’s a loser and doesn’t care. That’s the furthest thing from the truth.”

Anderson says ongoing care is now more important than ever before.

“There is an increased number of people who are becoming opioid dependent and there’s an increase in people who are dying from overdose,” Anderson says. “There are more people who are using opioids than ever before. The need for success on a continuum has increased significantly. I stress the word continuum – we have to be there to support the client when the client goes to make a change. We have to curry the culture where change is possible and realistic and positive. That it gives you back everything you had lost. It gives you freedom, amazing freedom that addiction takes away from people.”

Photo: Jack Soule/Human Beings of Hamilton

While community has proven beneficial for people living with addiction, even more so is the concept of promoting the possibility of change.

“The majority of people who are living in encampments don’t really want to be there but there are reasons that will keep them there,” says Anderson. “Addiction is one of them. I would never be grandiose to say stop using drugs and you won’t be in an encampment. That’s just foolish. But what we need to do and what we want to do is create a culture where change is possible.”

With decades of proof, men who thought their futures were bleak now have positive outlooks, successful families and work lives, and a new appreciation for support.

“It's just rewarding to be there for someone,” adds Kitchen. “To create space for someone, connect with someone, give them the opportunity to really believe in themselves. You can physically see the light and life come on in someone's eyes and it's an incredible experience.”

Wayside offers several programs, such as a family program where loved ones are brought in to help understand addiction and help ensure success once the men leave Wayside. They also offer subsidized housing for those who want to live in sober-living housing. A few men share a house, albeit with respective bedroom doors locked for privacy, living together like a family.

And it is a family – it’s been proven in court. Ron Tomblin is a realtor who procured six homes for Wayside House, which could then offer graduates subsidized and sober housing. He was cited by multiple officials for many bylaw infractions due to the living arrangements. They said it was a lodging house, Tomblin said it was a family situation. He even went to court to fight the infractions and won. All infractions were rescinded due to the recognition that these men live together as a family.

“What keeps me involved is that it really works for Wayside and, the best part of it all, it works for the guys,” says Tomblin. “These guys who follow the program, benefit from the houses and are very appreciative. There’s a personal satisfaction knowing I’m making a difference in the lives of these men.”

In the end, it all comes down to humanity and kindness to each other.

“When you are on the streets, the thing that gives you hope, and that for addicts will lead to sobriety eventually, is simple acts of kindness by people who you don't know,” says Matt.

“Somebody giving you a few dollars or a blanket or whatever, it makes you feel like you're worth it. While I was on the street, I saw a woman who was crying, and I had my sign up that said have a blessed day and I smiled at her. A couple of days later she came to me to say that day she was on the way to the hospital as her daughter had just passed away and she was going to pick up her belongings. She was thinking about killing herself, but she said she saw me smiling there and she changed her mind. She wanted me to meet her son who she said she wouldn't have seen again if it wasn't for me. You never know what somebody is capable of doing and it’s simple acts of kindness between each other that helps.”

A major fundraiser for Wayside is its annual walk, Step Up for Wayside, which also provides a community for those who have loved ones struggling with addiction or have lost loved ones to addiction. This year’s walk takes place at Bayfront Park on Oct. 19.