FOR THE LOVE OF HAMILTON

This regular feature highlights people from all walks of life who have embraced Hamilton as their new home.

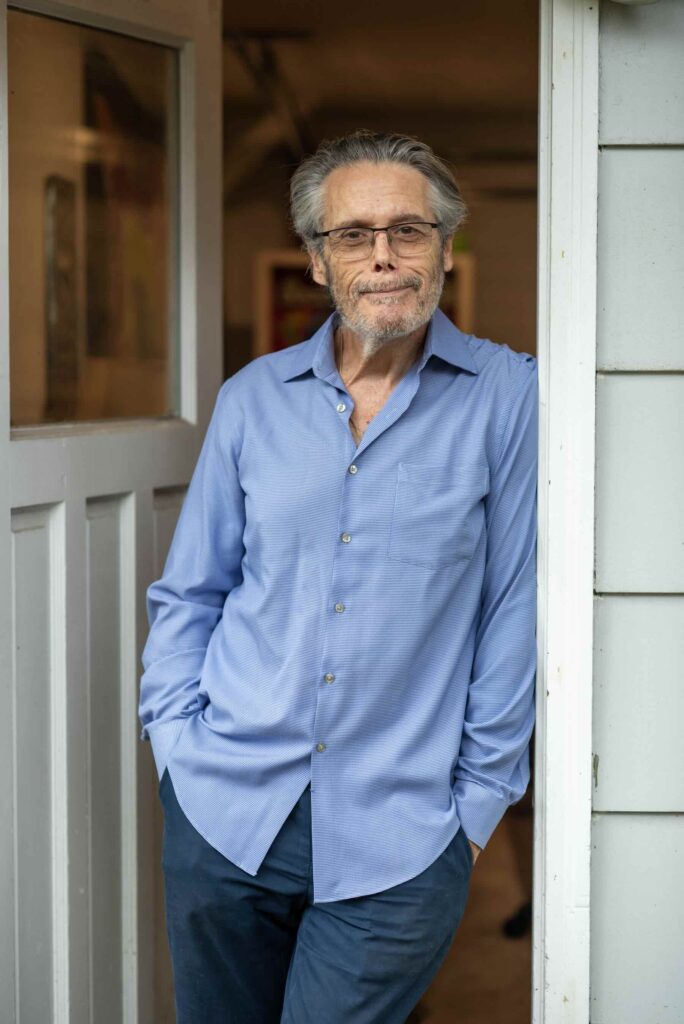

RALPH BENMERGUI was born in Morocco and came to Toronto as a child. His life has been constant reinvention. He has interviewed thousands of people on TV and radio, from celebrities to politicians to regular people, during a long career at CBC and later at JazzFM91. He has also hosted, written and co-produced critically acclaimed documentaries like My Israel, God Bless America and 5 Seekers and hosts two podcasts. He has served as executive advisor to political and academic leaders, while becoming an ordained spiritual director. In 2020, he released his biography. I Thought He Was Dead: A Spiritual Memoir. He is married and has four sons.

What prompted you to move from Toronto to Hamilton?

I'm fundamentally a Torontonian. I wasn't born in Canada. I was born in Morocco. But I was quite young when we got here to Toronto, and I'd say I spent over 50 years living there, and it got to a point for me where I felt like I didn't really recognize my city anymore. It seemed too full without the proper infrastructure for that to be OK. So everything was about urgency, making sure you didn't get a parking ticket. You have to pay to park on your own street. getting around. I have two older children and two younger children, and the number three child at the time was already going to school in Toronto, and he was anxious, sitting in the car, that we weren’t going to get there. Also, it had become very expensive. It's a much more expensive city than Hamilton. I need to live in a city, not a bedroom city, and Hamilton was a city, with its own character, so my wife and I started coming out here.

What kind of reaction did you get when you said you were moving to Hamilton?

Well, a lot of my friends are from the arts and culture community, so they weren't surprised at all. A lot of them know other people who had moved here. At the time, nine years ago, the affordability was really there. Unfortunately, today, the neighbourhood I live in now is too expensive for a lot of people, especially if they're raising their own children and they're in the arts.

How would you describe this city as a place to work as an author and overall creative person?

You know, in Toronto, I could go out for lunches with people, different people, networking all the time, and the next job would come from that. In Hamilton, I have spent almost the entire time working from home. like right now I'm in my office, which is our garage as well. It's insulated, it's nice. But I miss that kind of connectivity I had. When I got here, there was a lot of talk about music city and culture. I still don't find it's really come together that way. You know, I think there's a lot of creative people here but I don't think there's an infrastructure that supports being here.

You’ve been a broadcaster, a documentarian, a host, author, podcaster, an advisor to a range of leaders and you’re now a Jewish spiritual director. You’ve even been a standup comic and lead singer in a band. What ties together all of those points of your career?

Two things. One is storytelling. You know, any journalist will tell you they're telling stories. I've worked in communications as well, and it's really, how do you tell a story. So there's that, I think every one of them, from stand up to a spiritual director, it's about story. You know, my wife was a journalist for 15 years, and now she's a psychotherapist. And you know, we were talking about that a few days ago, and she said, “I listen to people tell me their story. I try to help them with their story.” The second is thing is loneliness. Right now, in the U.K., in their health ministry, they have a sub-ministry of loneliness.. And the World Health Organization just described loneliness as an epidemic. And so for me, that's a really important thing to try to help with, because I really find we're just all alone, privatized. We've privatized almost everything about our lives. And you raise your children alone, you try to find your work alone, and you go to the checkout counter and there’s no one there anymore. We just don't have that sense of public space and community that I think is really missing, and you can see it on people, and the pandemic just put an exclamation mark on it. It didn't come out of the pandemic. The pandemic forced us to look at it.

What does a spiritual director do?

We live in either a fundamentalist or a post-religious life, so there's a lot of talking about bigger questions that come up particularly as you get older. It’s like the Peggy Lee song, Is That All There Is, you just pay bills until some oncologist calls you one day and says you're dead. So my work is to talk to people. I use meditation techniques, guided meditations, breath meditation, just to get people centred. I don't care if my client is Jewish or something else, it's irrelevant, but I'm trying to help them with becoming a spiritual being and not a commodity. I want people to be able to examine what is my purpose? Do I have one? Where is the awe in my life? We are arrogant in our belief that we have dominion over the earth. We're not stewards. We're trying to conquer it.

There are half a billion galaxies in the known universe. I don't know how you could not think something bigger than us is going on out there, but we've become the biggest thing in the picture … And I think people are not going to church and synagogue and mosque and temple because the answers given are not adequate for him. They don't know what to believe in. So I try to help people to just navigate that and marry it to their troubles in life.

What would you say to someone looking to reinvent themselves or take on a new challenge later in life?

The only thing that's constant is change. So if you're available and understand that you're not in control of the narrative, it allows you to think differently and think, I guess, bigger, about what you can do. The other thing is to decide not to put limits on yourself. I constantly find myself in a position where I have no idea what's going on. But I always know asking a stupid question is a smart idea. And I also know that it's up to me. I have to fake it till I make it, but I get better at making it. So I just want people to go for it, because I've always been frightfully aware that life is really short. It's much shorter than we think it is. My grandmother came from Morocco when she was 83. She lived to 100 and when she was 97 or something, she said to my mother, ‘I was 14 (years old) 10 minutes ago.’ Life is a short-term gift.

In your book, you explore how North American society doesn’t value its seniors or the wisdom that comes with aging. What do we need to change?

The blessing and curse of our economic system for a lot of people, certainly not all people, is that you can live alone. So there's that idea that, why do I need to share my house with my parents? You know, they're kind of annoying. I don't want to live with them. And if your kids are still home after university, then they failed to launch. So anything except independent living, either be it individually or in a family, is considered unnecessary and not worth bothering. So in other cultures, because they don't have that, it's perfectly normal to have your parents live with you and your children live with you because you all need each other. Because we don't need each other, we can ignore each other. But the other part of it is, if you're 70 years old, you might buy one more car. If you're 27 years old, you're going to buy six or seven more cars, right? Your value is much higher as a commodity than mine, because I've kind of stopped buying stuff. So in a consumer society, older people have very little value. They're more of a burden, right? We don’t look for the wisdom. We need things like wisdom councils. You know, if you're in a craft or a trade, there should be a wisdom council. If you're in a business grouping, thereshould be a wisdom council. They should be localized in communities, too. In Hamilton, wisdom councils could give depositions at city hall. If it’s the conservation of aquifers, you get a retired engineer, and you get a retired hydrologist, and you get an urban planner, and they all have something to give but no one wants to hear it.

In public gatherings of people, everyone is mortified to tell you their age. They’re apologetic, because we don't value the journey. You're supposed to be forever young.

What prompted you to write a memoir?

I had stents put in my heart and then a cancer diagnosis, and I didn't tell anybody. I didn't tell anybody for several reasons. One is, I'm a private person. I've been public in my life and that makes you want to be more private in your personal life. And the other one was, if we're all just commodities, I would have then appeared to be damaged goods to people, and they would go, ‘Well, we can't hire him. He’s had cancer.’ So I sort of overcame that, because I felt like there were some things I wanted to talk about with people, and I didn't have a daily platform, which I'd had for years. And so I just decided to write the book. And the title, I Thought He Was Dead, my wife hated it. But I think that's a good title, because when you've been a public figure, and then you're not on every day … I'd go to a party and somebody would look at me, and I realized they were thinking I was dead.

What is your hope for Hamilton?

The aspiration isn't high enough in this city. I think Hamilton could become, and this would really turn things on its head, the greenest city in Canada. Imagine steel city, with fire coming out of a chimney, could become the greenest steel production, the greenest community, the greenest sustainable energy, the green everything. The people who aren't from Hamilton don't know about the green part of Hamilton. You know, my wife and I are on the rail trail for 20 kilometre rides, Chedoke, the Bruce Trail, Princess Point, Burlington Beach, waterfalls … When people come here and see these things, they can’t believe it. I don't think the leadership that I've witnessed since I've been here really dares to dream. We should be bold.

Why did you choose to live in Kirkendall and what do you love about it?

We spent a year visiting different neighbourhoods including Dundas and Westdale. Our real estate agent introduced us to the Kirkendall neighbourhood. We loved the house, Locke Street and proximity to the 403. We were sold.

Was there something that surprised you about Hamilton after moving here?

Yes, it was how much green space and great trails and waterfalls there were to explore just minutes away from our house.

What Hamilton arts or cultural events do you most look forward to attending?

Plays at Theatre Aquarius, The Playhouse cinema on any night, art crawls and Supercrawl. I wish there were some more live venues, especially for jazz.

Is there a book written by a local author that sticks with you?

John Terpstra's The Boys, Nothing the Same, Everything Haunted by Gary Barwin.

What is your favourite meal in a local restaurant?

Pizza and martinis at Cima on Locke.

What's Hamilton's best-kept secret that you've discovered?

Trails, from Princess Point, Bayfront on bikes, the trails at Winston Churchill Park, to the RBG Arboretum and the hike from Tiffany to Sherman Falls.

What does Hamilton need more of?

Two-way traffic and street life, parking and retail on Main. Beautiful modern architecture to complement heritage buildings in the downtown. Oh, and way more cycling infrastructure.

What does Hamilton need less of?

Poor air quality, and turf wars between downtown, Mountain, Ancaster, Stoney Creek, etc.

What is the one thing you brag about Hamilton to outsiders?

The calm that comes with a medium-sized city and the fact that you can say hello to people wherever you go. OK, that's two.

IF YOU’D LIKE TO BE FEATURED IN FOR THE LOVE OF HAMILTON, PLEASE CONTACT meredith@hamiltoncitymagazine.ca