Hamilton’s expensive fiction

False narratives that have guided planning decisions for decades have resulted in costly urban sprawl. It’s time to plan for the city that really exists.

Understanding the type of city you are helps communities plan for the future. If you are a tourist town, you gear infrastructure and communications to attract visitors and boost local business. If you are a tech centre, you focus on an innovation ecosystem and quality of life to attract talent to live and work in your city. However, if you are a bedroom community, you tend to facilitate development that gets people out in the morning, and back home in the evening. Approving new housing near highways is accelerated and the construction of supportive commercial clusters, like big-box malls, is prioritized.

So what type of city is Hamilton? There are competing answers to that question – some based in fact, others based in fiction. Let’s start with the fiction.

For decades, there has been a pervasive idea that Hamilton is a commuter suburb. The conventional wisdom, starting in the early 1990s, was that with industrial decline, Hamiltonians had to look elsewhere for work and thus the workforce had shifted to an “out-commuting” culture. More recently, Hamilton’s housing prices ushered in a new narrative that says waves upon waves of Torontonians are moving to Hamilton and thus Hamilton is full of commuters that make the trek to Hogtown daily. There are many problems with these assumptions, but two major ones stand out.

First, the actual data on where Hamiltonians work doesn’t back this up. Second, while operating under this false idea of the city, certain planning and investment decisions were made that were not properly focused on building the city that actually exists.

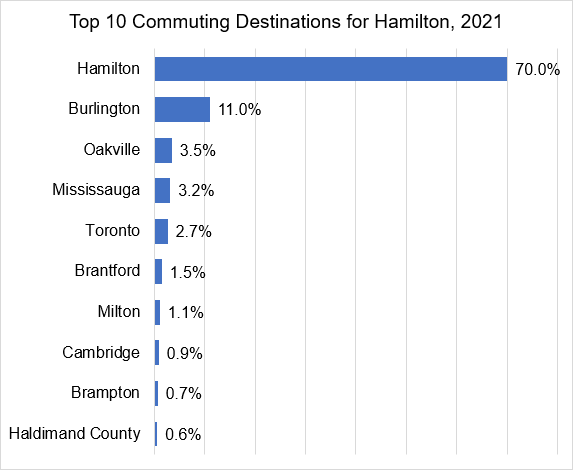

Let’s start with the data. Statistics Canada keeps track of commuting destinations each census. From the most recent 2021 census, here are the top 10 commuting destinations for Hamiltonians:

What this shows is that the overwhelming majority of Hamiltonians, 70 per cent, live and work in Hamilton. When they do commute out, the major destinations are Burlington (11 per cent), Oakville (3.5 per cent), Mississauga (3.2 per cent), while Toronto comes in at (2.7 per cent). Additionally, these percentages have remained roughly the same since 2006.

This means that most out-commuters are not even leaving Hamilton’s census metropolitan area, and they are working in neighbouring Burlington. Meanwhile, less than 3 per cent work in Toronto, which is completely counter to the narrative of Hamilton as a bedroom community for Toronto.

So, if the vast majority of Hamiltonians live and work in the city, where do they work within Hamilton? While employment is spread around the city, according to the City’s planning and economic development department, downtown Hamilton is the city’s largest employment node, with an estimated 26,305 jobs.

In terms of the types of jobs, a survey of downtown businesses revealed that there is a mix that includes government, professional and scientific, retail and entertainment, FIRE (finance, insurance and real estate), healthcare, social services, creative industries, education, and non-profits.

So what we have is a city where the vast majority of people live and work locally and where the single largest employment hub is the downtown, which contains a healthy mix of good-paying jobs from a variety of sectors.

Given these realities, how has Hamilton planned and invested in itself over the last number of decades? From an economic development perspective, the goals have been mixed. On the one hand, strategies such as downtown and waterfront renewal were developed to create a vibrant city with enhanced local quality of life in order to attract business and talent. On the other hand, new development has moved things in the opposite direction. In the last 20 years, growth has occurred on the outskirts in the form of urban sprawl. Specifically, while the population grew by about 14 per cent between 2001-2021, the urban area grew by 28 per cent.

This sprawl wasn’t by accident. It was facilitated by deliberate decisions. Hundreds of millions of dollars were spent to build highways that make it easy to get out of Hamilton. Some of these roads were connected to new business parks, but most resulted in adjacent subdivisions built on farmland advertising an easy commute out of town. Under this model, Hamilton is reduced to a peripheral community on the outskirts of the Toronto region, instead of a diverse city itself that invests in its own economic and social sustainability.

This is a familiar playbook used for GTA cities like Markham, Mississauga and Oakville, but did it make sense for Hamilton? Was there an equivalent investment that looked to build the future of the city that actually exists? For example, we are only now, in the 2020s, developing light-rail transit that will help people get in and out of the downtown, the single largest employment node, more easily. While other Canadian cities, including Ottawa, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver were developing rapid transit in the 1980s and ’90s, Hamilton decided to focus its money and efforts elsewhere. Even when regional GO transit was finally brought to Hamilton, it was initially set up as an out-commuting service.

Likewise, since the 1990s, Hamilton approved the tripling of the number of massive large-format big-box malls that were located beside these commuter neighbourhoods. Did the local market suddenly become three times as wealthy in order to justify this expansion, or did existing local commercial districts get cannibalized in the process, leading to the decline of older retail areas?

This debate is not unique to Hamilton, but it has real consequences for residents, not the least of which is in the impact on City services, infrastructure and property taxes. Simply put, sprawl is expensive. The City of Ottawa put a cost on sprawl and revealed that it costs $465 per person each year to serve new low-density homes built on undeveloped land, over and above what it receives from property taxes and water bills. That's up $56 from eight years ago. On the other hand, high-density infill development, such as apartment buildings, pays for itself and leaves the city with an extra $606 per capita each year, a financial benefit that has grown by $151 in those eight years.

It is not unreasonable to assume these numbers are similar for Hamilton. The cost of this sprawl is why existing streets in the city are not maintained properly, services are not what they should be, and why we are looking at big property tax increases year after year for the foreseeable future.

Needless to say, the status quo is not sustainable. Fortunately, as the city continues to grow, there is a chance to get things right. While the provincial government is forcing more sprawl on the city with its decision to open the Greenbelt, Hamilton still has the power to make game-changing investments that will focus growth for decades to come. That is what projects like LRT are all about. However, sustainable change will only happen by shedding the fictions that have guided past planning decisions and refocusing efforts on building the success of the Hamilton that actually exists.

Paul Shaker is a Hamilton-based urban planner and principal with Civicplan.