Life in the slow lane

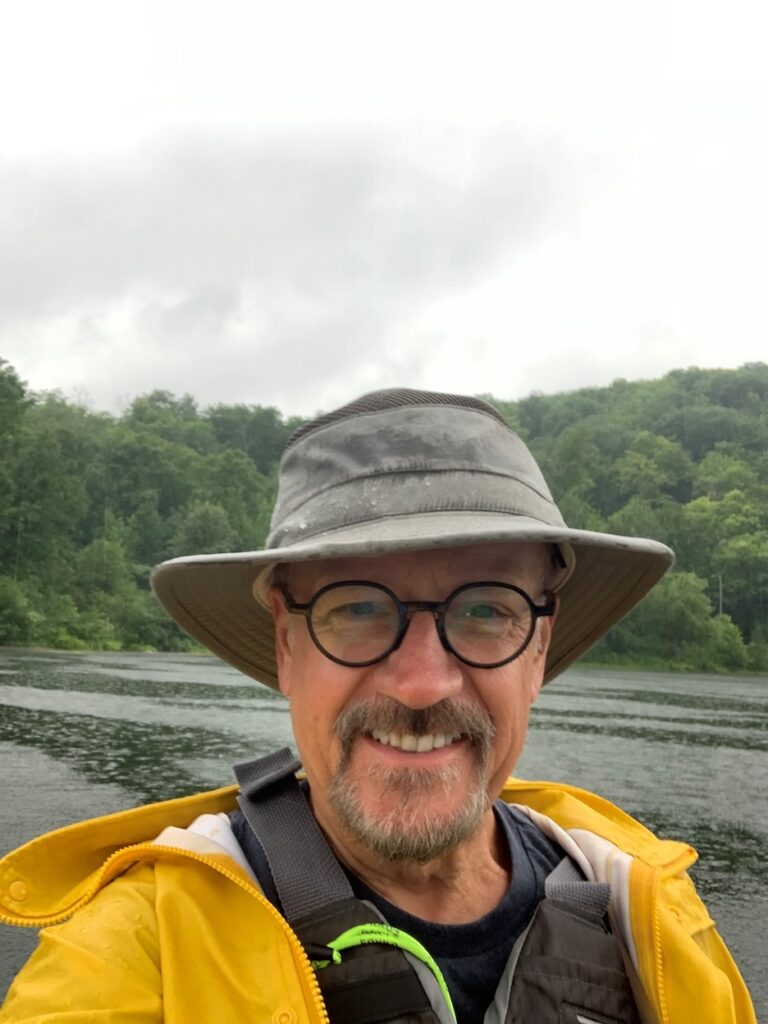

Dana Robbins’ time in the career fast lane has now shifted into a retirement of roughly 1,217 (and counting) days of walking nearly 10,000 kilometres, plus more than 1,800 kilometres travelled by kayak. His Type A personality has documented every step and paddle stroke. Here he shares his reflections on (mostly) solitary, slow-moving pursuits.

No matter what you make of what you read here, one fact is indisputable: I was not built for speed.

This will come as a surprise to no one who has spotted me on a hot summer day and wondered: “Why is there a giant pear on the beach? Is it a parade?”

But if I was not built for speed, it appears I may have been built for distance.

On Nov. 8, 2020, I slowly started moving … slowly.

I went for a walk.

It wasn’t a particularly long walk. Nor was it a particularly memorable walk; I can’t even recall my route.

But there was obviously something about that walk because when I got home I logged the distance on an Excel spreadsheet (Type A Personality Alert). And I have repeated some variation of that stroll on each of the roughly 1,217 days (at the time of this writing) since.

And, in the midst of all that walking, I fell in love with another slow-moving past-time – paddling. So as a pre-retirement gift to myself, I bought a 14-foot touring kayak and took to the water.

Occasionally, I enjoy these slow-moving activities with friends and family, most frequently with my wife Catherine. But about 80 per cent of the time I walk and kayak alone, by choice.

That means that for a goodly chunk of every day for coming up to four years, I have spent by myself … moving. Not quickly, sometimes glacially, but moving, on land and water. In total, I’ve covered 11,431 kilometres (9,557 walking, 1,874 paddling) at the time of this writing.

If you were to chart all that walking and paddling on a map, and a Type A personality definitely would, it would show that, virtually, I criss-crossed Canada, and then trekked south to the tip of the Florida Keys, before paddling to Havana, Cuba.

It appears I have evolved into an urban shark with thinning hair. If I stop moving, I fear I may die. Or at least go bald.

I have chatted with friends and colleagues about my slow-moving marathon, I’ve even posted about it online, and there is, invariably, one of two reactions: Surprise and/or quiet, but pointed, concern about my mental health.

These are perfectly reasonable reactions, given I’ve experienced both myself.

Surprise, for sure.

How is it that someone who has lived such a violently sedentary life has become so obsessed with moving? It is truly inexplicable to me. It’s as if I woke up one morning and discovered I could speak Mandarin!

And concern about my mental health?

It’s not lost on me that I became increasingly obsessed with walking and paddling during a particularly difficult time in my life. And even a casual review of my Excel sheet would reveal there is a definite relationship between the number of kilometres I log on any given day and how much stress I’m feeling.

It probably doesn’t take a psychiatrist’s couch to conjure metaphors of me moving away from, or towards, something.

Possibly.

Or, perhaps I’m just doing the clichéd thing that people my age do: exercising obsessively in hopes of delaying the invariably lethal punchline that always brings down the final curtain.

I don’t know.

I don’t really much care.

I just know that I have become deeply addicted to walking and paddling, to moving slowly through a life that has mostly been characterized by moving too quickly.

Of the 9,500 kilometres I’ve walked since starting this trek, some – too few – have been in glorious, oftentimes sun-drenched or otherwise romantic, locales like Madrid, Granada, Cordoba, Tangiers, London and Willemstad.

But all of those only came after my retirement last spring (and I’m really only including them here to establish my bona fides as a sophisticated cosmopolitan, a veritable bon vivant with a tail fin.)

The brutal truth is that most of the kilometres I’ve slogged have been in The Hammer, and because I still had a day job for much of the time I’ve been doing this marathon, a majority of my walks have been at night.

There are only so many times you can walk around your own block before your neighbours start pulling the drapes when they see you coming. So, to mix it up, four or five times a week I drive to a different neighbourhood in Hamilton, and walk there. I have covered the whole city, multiple times.

I’ve learned two profound life lessons during those hours alone on the pavement.

First, even if you move through life with purpose and intentionality, even if you are truly centred in the moment and connected to creation, you will still develop chafing and painful rashes in strange places.

Second, Penaten isn’t just for babies. (See Life Lesson #1)

So all that slow moving has clearly not gifted me with great wisdom, but I have learned, or been reminded, of some things about my adopted home as I’ve navigated Hamilton’s streets.

My two biggest takeaways:

- I love this city.

Truly.

I love the quirkiness of its neighbourhoods, the elegance of its historic streets, its still-human scale, the open-face friendliness of so many of its inhabitants, its giant trees and the ridiculous abundance of green space, the harbour and lakefront (what a gift to be a “maritime” city), the small-town distinctiveness of the “suburbs,” the bracing honesty of the industrial sector, the escarpment and, darest I mention them, our magnificent waterfalls.

- I hate this city.

Truly.

The degradation of so many of our public spaces, our oh-so-progressive shoulder-shrugging acceptance of the menace that settles over too many neighbourhoods when the sun goes down, the trash and filth that blights so many of our streets, the corrosive urban decay that gnaws at some neighbourhoods like a cancer.

I have a complicated relationship with the city. So best that we leave it at that.

PHOTO: Jon Evans for HCM

Walking or paddling, which do I love more?

When it comes to moving slowly, my favourite child is paddling.

For starters, I can do it topless without running the risk of someone barking at me, “Excuse me, ma’am, you can’t come in here like that.”

I didn’t even learn to swim until I was in my 30s, so this late-in-life affinity for being on water is almost as surprising as the Mandarin.

Hamilton is a perfect city for a paddler. There is, of course, the harbour and Lake Ontario. But also Cootes Paradise, Valens, Christie, Grindstone Creek and Lake Niapenco. (Dollars to doughnuts most readers don’t know where in Hamilton to find Lake Niapenco. Dollars to doughnuts that expression immediately reveals me as a really old guy.)

All those spots in our backyard served me well when I was still learning to stay upright in my kayak. And I still love them for a leisurely afternoon paddle when I don’t have a lot of time.

But Hamilton is also the epicentre of an incredible paddling eco-system. Within an hour’s drive, you can find no end of flat water delights – Big Creek in Norfolk (Ontario’s Amazon), Black Creek in Niagara, Grand River, Jordan Harbour, Big Otter Creek in Elgin, Rockwood Conservation Area, the Welland Canal and Lyons Creek.

You could spend a summer or two exploring just these, which I did.

But eventually I started to launch further afield, onto water where the likelihood of encountering any other humans is considerably slimmer. And, so, I made my way to Big Salmon Lake in Frontenac Provincial Park, the Saugeen River, Lac La Peche and Meech Lake in Gatineau, Source, Smoke and Tea lakes in Algonquin and, of course, the Barron River snaking through its spectacular granite canyon, the Nottawasaga River, Cold, Beaver and Gold lakes in Kawartha, the Gloucester Pool, Blackstone Harbour and …. too many more to count.

I struggle to describe how I feel when I’m on the water by myself, but “calm” would come closest.

I loved my professional life but it was a noisy one, and it demanded that an extreme introvert behave like an extreme extrovert. It also came with an expectation that I have an opinion on most everything.

Paddling has freed me of that obligation, and allowed me to be quiet.

PHOTOS: Courtesy of Dana Robbins

Although I mostly paddle alone, I occasionally paddle with my adult son Jacob. Last year, I gave him a photobook of rivers and lakes we’ve paddled together, and places I’ve paddled on my own that I hope he will someday visit, maybe after I’ve stopped moving altogether.

I cleverly titled it Paddling with Pa. (A shark with a flair for alliteration?)

In the flap of Jacob’s book, I listed 10 lessons kayaking teaches; they are a father’s clumsy, poorly disguised metaphors for life.

1. One stroke after another. That's the only way to move forward.

2. Paddle against the current when you are rested.

3. Pay attention.

4. Sometimes the stuff that scares us isn't really that big a deal.

5. Have fun, but don’t be stupid.

6. Paddle in silence. There is too much noise in life.

7. Be humble. (Kayaking has a way of reminding us that we don't know as much as we think we do.)

8. Be in the moment.

9. Plan ahead.

10. Allow yourself to feel awe. ("Look where you are.")

About the time this magazine hits store shelves, I expect to again be feeling awe.

God willing, I will be in Spain. A buddy and I are tackling a portion of the Camino de Santiago de Compostela. The plan is that we’ll walk from Sarria to the cathedral in Santiago, then onto the Atlantic at Fisterra, just under 200 kilometres.

We plan to walk long days, up to 35 kilometres on a few. We’ll walk with intentionality and purpose, but slowly. And likely oftentimes in silence.

So don’t be surprised if, at some point in early June, there are reported sightings of a slow-moving shark with thinning hair off the coast of Spain.

(Until then, pull your drapes.)

Note from editor Meredith MacLeod: Dana Robbins is the former editor-in-chief and publisher of The Hamilton Spectator who went on to executive jobs at Metroland Media. He had a 41-year career in newspapers before retiring in May 2023. I was lucky enough to be a reporter in Dana's newsroom at The Spec, and our creative director Will Vipond Tait worked as a graphic designer under his leadership, too. We both extend our thanks to Dana for writing this brilliant piece (after some hounding from me).