McMaster University will un-pave a parking lot and return it to paradise

Campus will undergo a profound transformation over the next decade as it renaturalizes west side, adds more housing and creates entry gateways.

A vision to transform the McMaster University campus over the next decade includes the renaturalization of what are large parking lots on the west side of Cootes Drive, more housing in the core campus in mixed-use buildings, and creating gateways features at the campus entrances.

Overriding principles of a campus master plan that will guide Mac’s development until 2033 are sustainability, climate change action and greening of the campus.

“McMaster is a beautiful, well-kept campus, and we are privileged to be beside, I would say, one of the world's wonders in Cootes Paradise. So we owe a responsibility to our surroundings,” says Saher Fazilat, VP of operations and finance at McMaster.

“I think there's been very thoughtful development of McMaster,” she says, “and we want to further enhance that. So, as opportunities arise, we take them.”

That includes creating more attachment of the campus to Main Street, including a transit hub and ground-floor retail for students and the neighbourhood, continuing the pedestrianization of the central campus, replacing asphalt with water-permeable pavers, linking green spaces in the core campus, and building green features into new buildings, including geothermal heating, solar roof production and, potentially adding to McMaster’s nuclear generation capacity.

Europe is far ahead of North America when it comes to mitigating climate change and reducing single-occupant car use, so McMaster was intentional in seeking out proposals for its campus master plan from consultants from around the world.

International design firm BDP, which has a division in Toronto, was the successful bidder. The project is the firm's first for a post-secondary campus in North America, after working on several in Europe.

“They won the RFP (request for proposals) through a competitive process because they've done some things that were bold elsewhere, and we were going bold with our climate and sustainability agenda,” Fazilat said in an interview with HAMILTON CITY Magazine.

The boldest move is a future renaturalization or rewilding of the acres of asphalt home to more than 1,300 parking spots to the west of Cootes Drive, which are surrounded by trees, creeks and trails.

The vision is to see this area become a part of Cootes Paradise, with a pond expected to eventually form over the lots when asphalt is removed.

Though the western end of the McMaster lands had once been earmarked for expansion, the area is a natural floodplain and unsuitable for buildings, says Yves Bonnardeaux, senior architect with BDP Quadrangle in Toronto.

“It’s really prone to flooding at any time.”

The idea is that as fewer cars come to campus, thanks to the future LRT, increased use of car-sharing, more on-campus housing, and more remote work and learning, the west land can return to its natural state.

There is no set timeline for that to happen but the university has committed to not further developing the area. The rewilding will help McMaster achieve its goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Recently, McMaster launched a program to allow drivers to share a parking permit if they don’t need to drive on the same days or times. That has resulted in fuller parking lots and the elimination of a 700-person waiting list.

A committee blending researchers and operations employees is developing a plan to naturalize the expansive western parking lots through increasing biodiversity with planting native flora and enhancing existing habitats so that they become part of the natural Cootes Paradise ecosystem once again.

The committee is considering feedback from adjacent landowners and the community, as well as Indigenous leaders as it formulates a plan for a long-term natural reclamation project. The renaturalization process will be used as a living lab for McMaster students and researchers and will be an Indigenous gathering space, too.

Rewilding projects are happening around the world, including the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) protected corridor, the restoration of the Fresh Kills landfill in Staten Island, N.Y., into a naturalized park, and the European Green Belt, along with major initiatives in Mexico, Costa Rica, Australia, and Britain.

Formally established in 1927, Cootes Paradise sanctuary is significant as a migratory bird flyover zone and is home to a wide variety of flora and fauna. Featuring over 320 hectares of marshland, 16 creeks and 25 km of shoreline, Cootes Paradise is under the protection of the Royal Botanical Garden. Cootes is home to a thriving population of trumpeter swans, red knots, double-crested cormorants, great blue herons, and in recent years bald eagles, who have made their home in Cootes Paradise.

McMaster’s last campus master plan was completed in 2002, with some updates in the intervening years. The new version will be reviewed yearly and any development or infrastructure projects on campus will pass through a design review committee to ensure they adhere to the plan.

McMaster has aspects of both being an urban university and as well as a standalone campus in a more rural setting, says Bonnardeaux. “It has the meandering valley, which is really quite stunning, and an amazing place to be. But on its urban edge, it has largely gone on without much visioning.”

When McMaster outgrew its Toronto home, the campus in what is now the Westdale neighbourhood was founded on lands gifted by the Royal Botanical Gardens in 1930.

While McMaster went through a massive expansion in the 1960s and 1970s, driven by the baby boom, some of it was done in a “haphazard way,” says Bonnardeaux. Though the central mall green space was retained, the construction of the McMaster University Medical Centre shifted the street grid and cut off the university from Main Street.

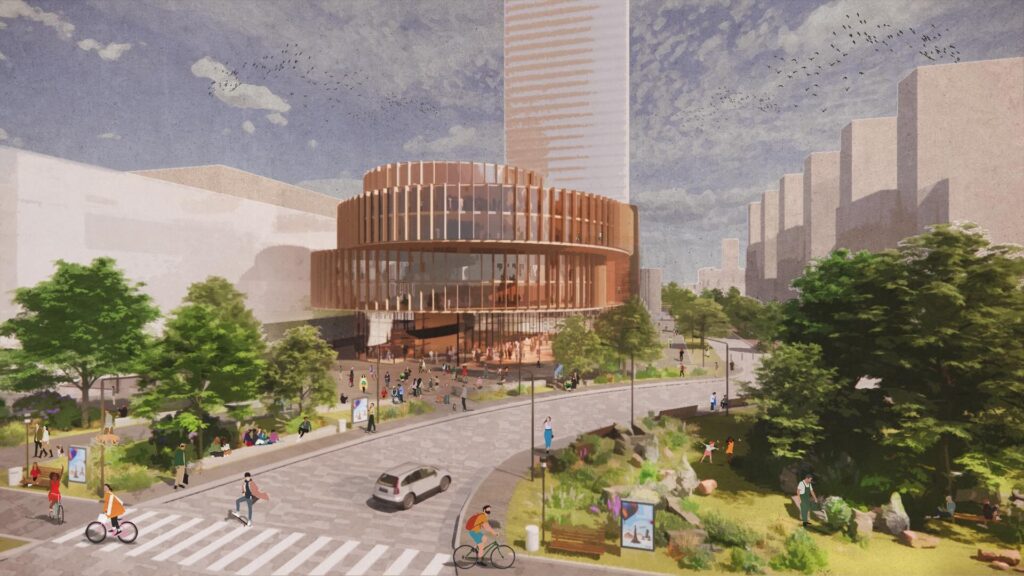

“So the approach to the university right now is kind of unsatisfying, both from Main Street and from Sterling because you enter from parking lots, and so part of our vision was to create these two big entry points,” he says.

“From an urban design standpoint, we thought the university was really lacking a sense of arrival, like a sense of entry, which is why we created a Main Street West gateway with a large plaza and a signature building, to make sure that you feel like you've arrived.”

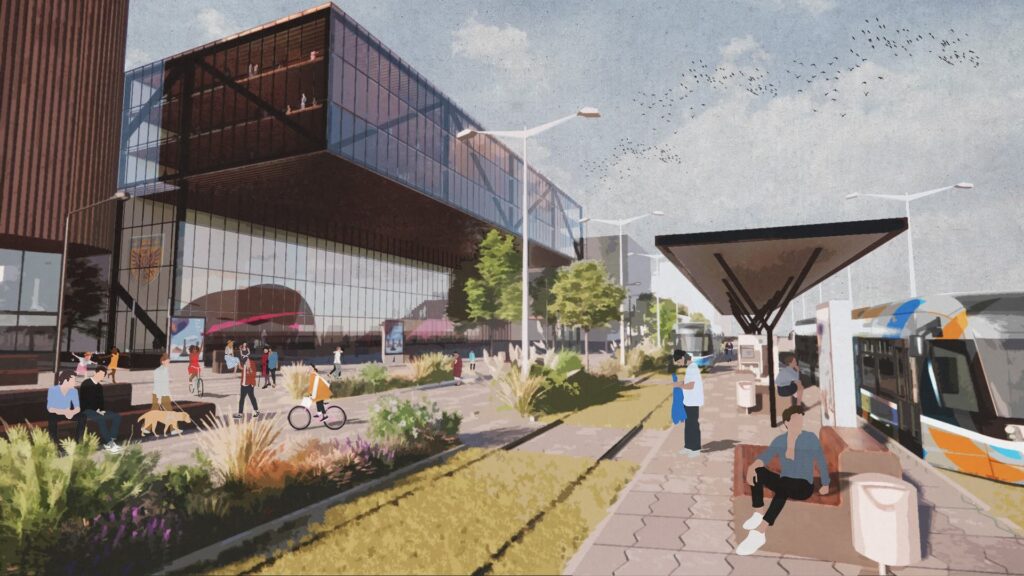

“If you start walking in from Sterling, you’ve got to cross two lanes, then a parking lot and another two lanes, and then you get to the pedestrian zone. So that's definitely something we wanted to fix. And we also wanted to leverage the LRT project that's going on Main Street. So we've proposed a multimodal transportation station that would include the LRT stop and GO buses, along with bicycle storage, as well as providing places for parking of cars in a multi-level structure.”

The vision is for a gateway to the campus from there featuring a signature entry pavilion building, perhaps combining academics and housing, along with a plaza around the LRT.

And when an expected drop in car traffic arrives, the parking structure’s design allows for transformation into an academic building.

“It's new thinking, but it’s more common in Europe, about how to plan ahead for the demise of the car. And I'm not saying that we're not going to have cars in the future, but there will be a kind of Uber-fication of the world, where people will be sharing cars.”

The plan is a 10-year strategy for a campus that is home to more than 47,000 students, faculty and staff, says Fazilat, who previously worked on campus master plans for Western University and for Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson University). She said the chance to guide McMaster’s campus master plan creation and implementation was a big factor in her decision to leave her job as chief administrative officer for University of Toronto, Mississauga.

“The education sector is a changing landscape of diverging trends, driven by a significant shift in the flexible ways that students learn, work and think,” Sue Emms, principal and head of education at BDP, said at the time of the plan’s release.

“This is a design rooted in sustainable connectivity that will provide a physical transformation across the campus. It is also an expression of a clear vision to create more civic space and build an effective ecosystem that is engaged with Indigenous, local, national and global communities. It is a new civic face for the institution.

“This plan imagines places and spaces that can create impact, foster ambition and inspire transformation. We must develop in a way that reflects and supports the quality of the education and research taking place here,” said David Farrar, president of McMaster University about the plan.