Musical collaboration offers healing on the road to reconciliation

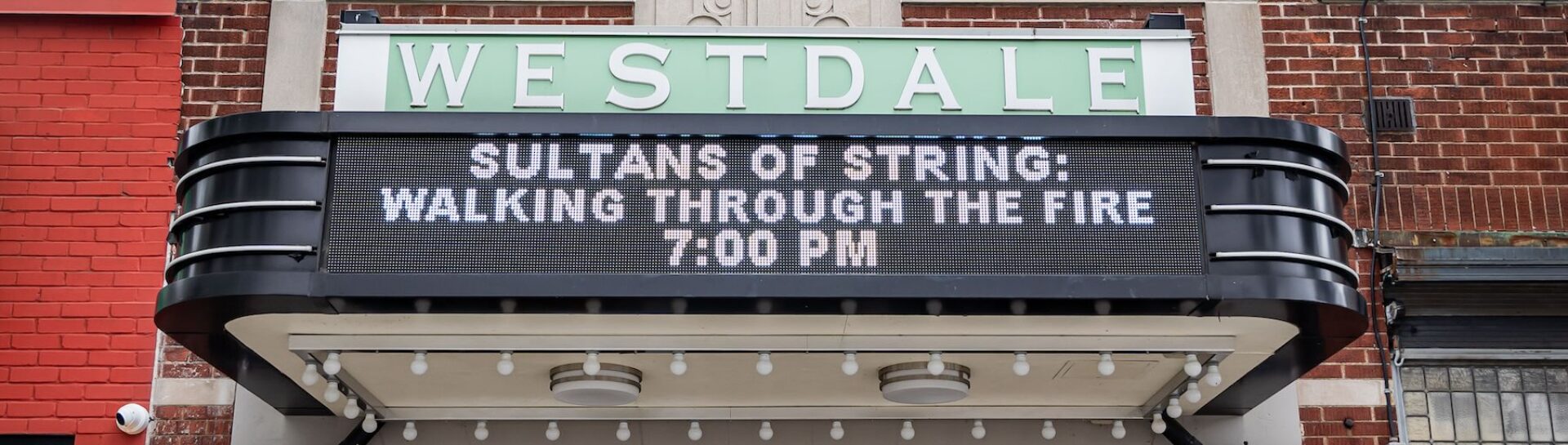

'Visual album' Walking Through the Fire brings together Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists to explore joy, along with the pain of genocide, residential schools, culture loss and displacement. It screens at The Westdale Nov. 17.

When violinist and Sultans of String founder Chris McKhool heard from an Indigenous elder that he should be shining a light on the history, culture and stories of Canada’s original inhabitants, he didn’t hesitate.

The instrumental quartet with a global fusion sound had just finished its eighth album The Refuge Project when an artist on the tour, Ojibwe scholar, elder and poet Dr. Duke Redbird challenged McKhool to tackle Indigenous awareness as he had with the issues surrounding refugees and new immigrants.

“It was a very direct call to action and definitely propelled the idea forward,” says McKhool. “So I started reaching out to Indigenous artists that I already had known or worked with, like Coast Tsm’syen singer Shannon Thunderbird, and Ojibwe artist Marc Meriläinen, and started having conversations with them about who would make for interesting collaborators on the project. And at one point I had a map of Canada stretched across my desk, and I thought to myself, let’s make this project span from coast to coast to coast.”

That search resulted in bringing on board the Métis Fiddler Quartet, The North Sound from the Prairies, blues singer and JUNO winner Crystal Shawanda, guitarist Don Ross, the Northern Cree powwow group, guitarist and singer-songwriter Ravan Kanatakta, Dene singer-songwriter Leela Gilday, and Inuit throat singers.

Photo: Sultans of String

The resulting album, Walking Through the Fire, came out in fall 2023 and features songs in English and Indigenous languages that celebrate nature, pay tribute to children lost to the horrors of residential schools, and explore the ongoing effects of separation of families and loss of culture and place.

The album, a 50-date live concert series and now a film were all created in the spirit of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action that asks for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to work together to find a path forward, says McKhool, an Ottawa native, who moved to Aldershot eight years ago.

“We know that as a society we can’t move ahead without acknowledging and reflecting on the past, and before reconciliation can occur, the full truth of the Indigenous experience in this country needs to be told, so this film calls on Indigenous artists to share with us their personal stories, their experience, and their lives, so we can continue our learning about the history of genocide, residential schools, and of inter-generational impacts of colonization.”

As the tour moved across Canada, including appearances at the Edmonton Folk Festival, opening up for Robert Plant, performing with symphony orchestras in Toronto and Winnipeg, and a stop at Hamilton’s Westdale theatre in June, concert videos, behind-the-scenes B-roll, and interviews with the artists were captured.

All that material has now been woven into what Sultans of String call a visual album. The Walking Through the Fire film will be screened at The Westdale on Nov. 17. The film will be followed by a Q&A session with the artists.

“It is an exceptional place to play, being a beautiful, classic theatre, as well as having a gigantic screen, and a wonderful sound system. They are also very warm and community-minded people, and really care about showcasing original art, and creating community and understanding through their programming. I am in love with the place,” said McKhool.

McKhool, who co-founded Sultans of String 20 years ago, says the film shines a light on Indigenous music, its profound storytelling role, and the diversity and complexity of the cultures across Indigenous communities.

“One of our goals is to bring Indigenous music more into the mainstream to be shared more broadly across our country. In addition to these very compelling stories, the music is also mixed in 7.1 surround sound, so when you are sitting there in the audience, you can hear the orchestra playing all around you. It’s an absolutely fantastic immersive experience.”

All lyrics come from the Indigenous artists, while Sultans of String, who are four-time Juno nominees and seven-time winners at the Canadian Folk Music Awards, contributed musical parts and arrangements. Much of the album was recorded at Jukasa Studios, an Indigenous-owned studio in Ohsweken.

Before any music was written, Sultans of Stringbrought on Indigenous musicians, designers and filmmakers as advisors and assured the artists that they would maintain ownership of their original and collaborative musical elements and lyrics. The project abides by the Statement on Indigenous Musical Sovereignty.

“So that went a long way to developing trust in the project and our intentions. It was also important to be very clear that we did not want to take up space in the Indigenous world, but only add to the opportunities available for these artists. For instance, Sultans of String received some arts council funding from the non-Indigenous streams of Canada Council and Ontario Arts Council for this project, and then used this money to pay Indigenous artists, never touching any Indigenous funding streams.”

Walking Through the Fire was performed with a number of orchestras and those orchestral charts were provided to the Indigenous creators, with the hope that will lead to more performances of the works, says McKhool.

The music and the film explores difficult topics but it also showcases “the joy of Indigenous culture, a culture that survived despite attempts to eradicate it, that includes gorgeous melodies and a great sense of humour and community.”

The screening will be twinged with sadness, following the Nov. 4 death of Indigenous lawyer and senator Murray Sinclair, who led the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. McKhool met Sinclair two years ago and his support helped to fuel the Walking Through the Fire project.

“I was taken aback by his gentleness, his generosity, his sharp wit, and his incredible intellect,” recalls McKhool. “He impressed upon us the importance of music in cultural revitalization, and the critical nature of our work, cooperating and collaborating with Indigenous artists, and using our platform to share the Indigenous art we have made contact with, including using Indigenous languages in our project so they don’t become lost.”

Audiences will be both inspired by the work of Indigenous people to recapture and preserve their culture and leave hopeful about the possibility of reconciliation when “Indigenous artists welcome allies into the circle who want to learn more, want to be present, and want to do better as humans,” says McKhool.

“This country has a history that has been ignored, distorted, twisted to suit colonialist goals of destroying a people. We are so fortunate for the opportunity to work with these Indigenous artists, sharing their stories, their experiences, and their lives with us, so we can continue our work of learning about the history of residential schools, genocide, and intergenerational impacts of colonization. Music has a special capacity for healing, connecting, and expressing truth.”