New Faces of Leadership

Three accomplished Indigenous women, Jaimie Lickers, Santee Smith and Savage Bear, are forging new paths by taking on key roles in business, academia, law and the arts in Hamilton. HAMILTON CITY Magazine learns about their journey, what drives them and the future they dream about.

The tides of leadership in Hamilton are shifting.

Indigenous women are taking charge and moving into high-profile positions across the city. In this issue, we look at three intersectional trailblazers who have been appointed to crucial roles in banking, law, business, academia and the arts.

This wave of new Indigenous female leaders should come as no surprise. Just 25 kilometres southwest of the city sits Six Nations of the Grand River Territory. Its band membership of 25,660 makes it the largest population of First Nations people in Canada.

As they forge new paths in fields traditionally dominated by white males, these women are working to dismantle old power structures and improve the visibility of Indigenous communities, their culture and their history throughout Hamilton.

They are also encouraging the next generation of Indigenous peoples in Canada to imagine themselves in prominent positions of influence and dream big about their future.

JAIMIE LICKERS | Vice president, Indigenous Markets at CIBC;

Chair, Hamilton Chamber of Commerce

Jaimie Lickers has nothing left to prove. The 40-year-old member of the Onondaga Nation from the Haudenosaunee community of Six Nations of the Grand River has a laundry list of awards, accolades and achievements to her name.

But her illustrious legal career was born from a desire to defy expectations placed on her as an Indigenous woman practising law.

“When I went to law school, a lot of people assumed I would practise Indigenous law because of my racial identity,” she says. “But I’m stubborn. And if you imply that I should do something, or you tell me I can't do something, then I'll do it just to prove you wrong.”

After graduating from law school at Queens University, Lickers took a job at the prestigious Bay Street law firm Blakes and became a corporate commercial litigator.

“I wanted to prove that any Indigenous law student can excel and succeed and contribute to the legal profession in every practice area, not just Indigenous law.”

But after two years of working on high-profile cases, Lickers lost interest in big law. “I wasn’t passionate about the issues that were being litigated. I wasn’t personally invested in the outcome. I thought, ‘Dammit, they were right. I should be practising Indigenous law!”

After moving to Gowlings WLG, the first national Canadian law firm to locate in the Hamilton region, she has specialized her practice in Indigenous trust and tax law for almost a decade. Lickers has worked on several precedent-setting cases for First Nations clients. She became the first Indigenous woman in the firm's history to make partner and the first Indigenous person to hold a management position in the firm when she became the national leader of the Indigenous Law Group.

But perhaps what’s even more impressive is that Lickers achieved all of this while being a single parent to a two-year-old daughter.

“Single parenting, while trying to build a successful law practice and make partner at a firm, was not easy. But it was important to me,” says Lickers. “I'm a better mother when I am fulfilled both personally and professionally. So we figured it out.”

And figuring it out sometimes looked like Lickers getting up at 3:30 a.m. and working for three or four hours before she got her daughter off to daycare and then went to the office.

“If my daughter was sick or there was a snow day at school, she would come to my office and camp out under my desk. She became a fixture at the firm. The assistants would print off colouring pages for her.”

One of Lickers' other impressive achievements, for which she was awarded the 2017 Lexpert Zenith Award, was her role in securing legislative change to end discrimination against Indigenous naming traditions in Ontario. Her work helped pave the way for recognition of Indigenous naming practices, allowing for the registration of the birth of a child using a single name in accordance with the child’s traditional culture. Under previous law, children had to register both first and last names.

“I don't know that there is a more powerful career to have than one that allows you to shape the rules of the game that we as a society operate by,” says Lickers. “People often mistake the law for what is moral. And those two things don't always go together.”

Today, Lickers is vice president of Indigenous Markets at CIBC, where she leads a national team of trust and lending experts who provide financial services dedicated to Indigenous Nations, businesses and individuals.

In February of this year, she was named chair of the Hamilton Chamber of Commerce, the first Indigenous person to both sit on the board and become chair. One of her key priorities for her first term is to deepen the chamber’s engagement efforts with the Indigenous community and Indigenous young people.

The goal is to help local businesses become more engaged with the urban Indigenous community in Hamilton and surrounding communities, like Six Nations and Mississaugas of the Credit, to create programs such as apprenticeships or internships, scholarships and summer positions for young people.

“That’s how you're going to integrate and increase the representation of [the Indigenous] community within your business. I love Hamilton. I love living in Hamilton, and I love working in Hamilton. It’s part of the traditional territory for my people. Lots of Indigenous people live in this community, too. And we have to think about what we want the city to look like in five or 10 years.”

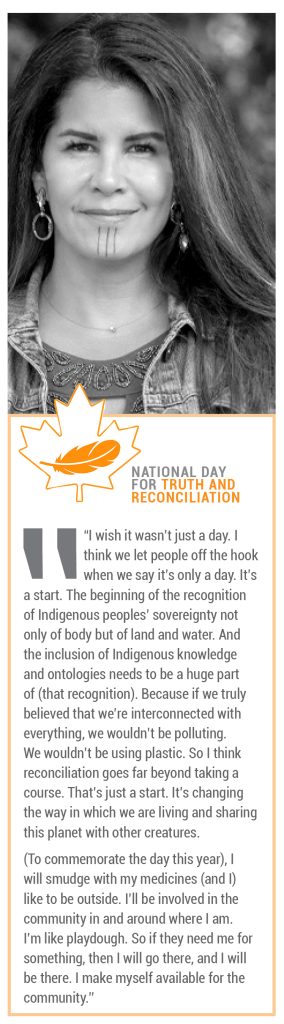

SANTEE SMITH | Founder and managing artistic director, Kaha:wi Dance Theatre;

Chancellor, McMaster University

Everyone has a purpose in life, according to Indigenous philosophy. Something they’re put on this earth to do.

For Tekaronhiáhkhwa/Santee Smith, that something was art.

Smith is a multi-award-winning Kahnyen’kehàka (Mohawk) dancer, potter, designer, producer, choreographer and multidisciplinary artist of the Turtle Clan from Six Nations of the Grand River.

“I come from a long line of creatives; people and ancestors who have made their livelihood out of their creativity,” says Smith. “That’s pottery, that's beadwork, that's corn husk doll making. My great uncle, Jay Silverheels, was the actor who played Tonto [in the Lone Ranger].”

A world-renowned Indigenous performer, Smith has built an impressive body of work elevating Indigenous knowledge, creativity and artistry, as well as sharing powerful and often overlooked stories about Indigenous communities.

At 11, Smith was accepted into Canada’s National Ballet School, where she trained for six years. While she excelled in the program, she left before graduation. Her time away from home left her feeling disconnected from her Mohawk identity and yearning to hear stories that reflected her First Nations background.

“I was a little bit disillusioned with the colonial aspects of the ballet world and telling European stories. Nothing reflected who I was as an Indigenous person. I wasn’t learning anything in terms of Indigenous artistic practices and processes. I wasn’t seeing a different perspective. I knew this wasn't going to be fulfilling enough for me, so I decided to stop.”

Smith returned to Six Nations, graduated high school and then went to McMaster, where she received degrees in both physical education and psychology. Years later, she also earned a master's degree in dance from York University in Toronto.

While considering a career in clinical psychology, Smith was pulled back into the world of dance by a group of artist friends keen to see her return to her craft.

“I was asked to choreograph a dance for a documentary by the National Film Board of Canada called The Gift, directed by First Nations actor and musician Gary Farmer. He set me up with a little studio in Toronto with some music and said, ‘Tell the story of Sky Woman. Tell the stories through movement [about] corn, beans and squash, the three sustenance foods that are very much intertwined,” says Smith. “And I was sitting in the studio just a little bit amazed at the possibility that I could create movement and dance that reflected who I was and some of the stories that came from my community.”

Smith went on to found her own dance company, Kaha:wi Dance Theatre, where she is also managing artistic director. With locations in both Six Nations and Toronto, the company has won a slew of awards for various performances, including, most recently, The Mush Hole, a theatrical dance performance about Canada's first Indian residential schools.

“My great grandmother attended the Mohawk Institute Residential School at the age of two or three until she was 15. She grew up in the Mush Hole. And my grandfather went to the Mush Hole, too. I grew up not knowing anything about their stories; it was hidden, silent, and shameful. ‘Don't talk about it’. Through my artistic work, I'm processing my personal family story and my own relationship with intergenerational trauma.”

Smith’s artistic talent goes well beyond dance. A skilled multidisciplinary artist, she is also a celebrated potter. Ceramic traditions have deep roots in her family: her grandmother Elda "Bun" Smith is credited with reviving the Indigenous artform that almost disappeared during the colonial period. Her parents also own a pottery studio, Talking Earth Pottery in Six Nations.

Earlier this year, Smith unveiled her new public sculpture, Talking Earth, a nod to her parents’ studio, as part of the permanent collection at The Gardner Museum in Toronto. A massive 330-pound ceramic earthen vessel, the piece has been cracked and reassembled into its classic shape with etched fragments held together on a metal frame, signifying trauma and healing in balance together.

Since 2019, Smith has also been the Chancellor of McMaster University. She is just the second woman and the first Indigenous person to hold the position.

“[When taking on the role of Chancellor] representation and what it would mean for up-and-coming Indigenous students was important to me. I wanted to be a positive role model and to be able to talk in a different way in that type of leadership role.”

She has implemented “subtle but impactful” changes while acting as the honorary head of the university, including recognizing Indigenous veterans at the Remembrance Day ceremony and making The Mush Hole part of McMaster’s alumni events.

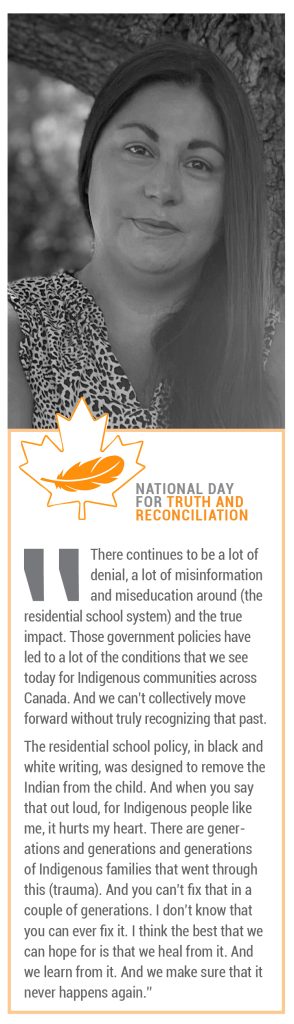

SAVAGE BEAR | Director, McMaster Indigenous Research Institute (MIRI); Assistant Professor, McMaster University

Savage. It’s a derogatory term that’s historically been used to shame and dehumanize Indigenous people.

But Savage Bear won’t be shamed. Formerly Tracy Bear, the award-winning Canadian scholar and director of the McMaster Indigenous Research Institute (MIRI), reclaimed the word Savage by legally making it her first name earlier this year.

“I haven’t felt connected to the name ‘Tracy’ for a while. I’ve been thinking about a new name for a long time, and nothing ever felt right,” the 55-year-old mother of three says. “Then I accidentally called my granddaughter ‘a little savage’ and remembered that my mom used that as a term of endearment for her grandchildren. The name appealed to me and matches my last name remarkably well. It fits my unconventional, often challenging nature. Plus, ‘Uncivilized’ was too long.”

Bear is a Nehiyaw’iskwew (Cree woman) and member of the Montreal Lake Cree Nation in Saskatchewan. She credits her success in life to being raised by strong Indigenous women, her mother and grandmother, who always believed in her and fundamentally shaped the person she is today.

“I'm here to break a new trail for other amazing Indigenous scholars, leaders, and activists that come along. If there's a trail to be broken, I'll break it,” says Bear. “But I know I stand on the shoulders of giants: amazing Indigenous women, scholars, grandmothers, pushers, doers and activists. I wouldn't be here if not for them.”

Last year, Bear became director of the MIRI, holding joint academic appointments in the faculties of Social Sciences and Health Sciences. At MIRI, she’s built a team of Indigenous female scholars to help her run the program based on shared values of community and reciprocity.

“This isn't our territory. As much as [I’m] in a leadership position, it doesn't matter who you are, you need to know where you tread,” says Bear. “You need to know the land and the people of the land. This past year has been getting to know my colleagues, the students, and external and internal stakeholders here and in and around Hamilton.”

As the program's director, one of her primary goals for MIRI is to build a Prison Education Project at McMaster. This project is an arm of a larger initiative called Walls to Bridges, an educational program based in Waterloo that brings incarcerated and non-incarcerated students together to study post-secondary courses in jails and prisons across Canada. Earlier this year, Bear was named the new national director for the Walls to Bridges program.

“Part of my platform when I was considering McMaster was, “Is there space for this [program]? It's a huge part of my work. Being as privileged as I am, [it’s important for me to uplift] my sisters and brothers. Because [these incarcerated individuals] are some of the most critical thinkers and amazing students I've ever come across.”

Before her role at McMaster, Bear worked at the University of Alberta, making significant contributions to Indigenous scholarship. She was the director of the Indigenous Women & Youth Resilience Project, the academic lead on Indigenous Canada, and assistant professor of Native Studies and Women’s and Gender Studies. Her PhD thesis, Power In My Blood: Corporeal Sovereignty Through a Praxis of Indigenous Eroticanalysis, won the Governor General's Gold Medal Award in 2016.

And while she’s proud of all her accolades, the positive feedback from the Indigenous community in Alberta during her time at the university left the most lasting impression.

In 2014, the remains of 28 First Nations people, dug up nearly 50 years at the former Sharphead reservation, were found stored in the basement of the University of Alberta’s anthropology department. Bear was instrumental in having those remains returned to the earth and given a permanent gravesite at Maskwacis.

“We had a quiet ceremony, and it was one of the most beautiful, poignant moments in my life. Because for years, I had been raged at, and I understood where that frustration was coming from. There was one elder who I thought hated me. Every time I saw her at a meeting, my heart would sink. And at the end of it all, she came up to me, and she was a big woman, and she just put her arms around me and hugged me for a long time. And then she whispered in my ear, ‘You did a good job, my girl.’ And that’s great validation. That's what makes my heart sing.”

Bear is also the academic lead for Indigenous Canada, a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) designed to help Canadians understand the history of Indigenous peoples. Though the program was hugely successful when it first launched in 2017 – with more than 35,000 learners

(overtaking Dinosaurs as U of A’s most-watched course) – its popularity exploded when Canadian actor Dan Levy promoted it on his social media channels in December last year. Current registrations for the program are close to half a million.

Though she has lived all over Canada, Bear now calls Hamilton home. Living near Bayfront Park, she says she has fallen in love with the city.

“Hamilton feels like home already. I love the grittiness, and I love the realness. The authenticity is there. I’m an avid hiker and biker, so I love the trails. And I love to eat, and Hamilton has some amazing restaurants. This city was made for me.”

And she wants to put Hamilton on the map when it comes to Indigenous scholarship.

“I want McMaster to be the go-to when people think of Indigenous research and Indigenous studies. In five years [when her stint as Director at MIRI is over], I see myself with a boatload of Indigenous scholars, who might not have otherwise been there, graduating, walking across the stage with a fulsome Indigenous community on campus, where we are attracting not only students but faculty and staff from all over Canada.”