Precision is turning the tables

Burlington’s Precision Record Pressing is one of North America’s leading vinyl manufacturers, producing 16.5 million albums a year.

There is little doubt vinyl is having a moment.

Well, more like a 17-year moment. Record sales have been on the upswing since 2006 and last year overtook CD sales for the first time since 1987.

In a world dominated by streaming, vinyl is still a force.

Why is that? Nostalgia? Probably.

Better sound? There are many audiophiles who say the audio of records runs circles around digital. So check that one, too.

Is it a yearning in a digital age to have something to hold in one’s hands? Likely.

“Even for young people, it’s something tangible. There’s lyric notes and posters and album art. And you have to get off your ass to flip it over,” says Ernie Addezi, senior vice president at Precision Record Pressing in Burlington.

Then there is ritual to it all: searching for the record you want to hear, sliding it out of its cover, choosing which side to listen to, placing it on the turntable, setting down the needle and hearing that unmistakable crackle.

The listener hears the songs in the order in which the artist intended. And there is a multisensory experience to records – sound, sight, touch, even smell. They have to be handled carefully, and that fragility makes them precious. You can watch the record spin and see the diamond in the stylus travel over the grooves, seeming to coax the music through your speakers.

In comparison, listening to streamed music feels like something that happens to you, rather than by you.

It’s also apparent that many people buy vinyl as collector items, perhaps even as art pieces. According to music data company Luminate, only 50 per cent of vinyl buyers actually have a record player.

And then there is this retro-tech resurgence among Generation Z (and some of Generation Alpha) that is making digital point-and-shoot cameras popular again, along with old PCs, game consoles and even typewriters.

When CDs swept in 40 years ago, lots of manufacturers got out of the vinyl game. But rumours of the death of records were wildly exaggerated it turns out.

Last year, vinyl album sales in the United States grew for the 16th consecutive year, according to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). The 41.3 million EPs/LPs sold was up more than 45-fold compared to 2006 when the vinyl comeback began.

So in 2022, vinyl albums earned $1.2 billion, compared to $483 million for CDs, says the RIAA.

In Canada, sales tracker MRC Data reported 1.1 million vinyl records were sold in 2021, an increase of 21.7 per cent over 2020 when sales dipped amid COVID-19 and supply issues. The 2021 numbers topped the previous record of 1.03 million units sold in 2019.

Precision Records has been pressing vinyl since 2016. It formed as a partnership between Czech Republic-based GZ Media, the largest vinyl record manufacturer in the world, and Canadian music distributor Isotope Music.

Precision puts out 1.4 million albums a month from its 20,000-square-foot manufacturing facility in a business park in the Guelph Line and Harvester Road area. A little over two years ago, Precision had to add a second location 10 minutes away, a 100,000-square-foot packaging plant and warehouse just off Hwy. 403 at Burloak.

Precision is now among North America’s largest pressing plants and employs 300 people who pump out records 24 hours a day, five days a week.

Watch a behind-the-scenes video of record manufacturing

Precision produces for independent labels, bands and solo artists but also the biggest titles of the major labels – Universal, Sony, Warner and Disney. It ships all over North America, with 80 per cent of its albums going to the United States.

During the pandemic, booming record sales led to a backlog of six to eight months to get a record pressed. Precision invested in new presses and now its lead time is down to about 10 weeks. GZ North America has record plants in Memphis and Nashville, too.

Addezi is fascinated by vinyl technology – basically a plastic platter of grooves that produces sound when a needle passes over them – and how digital MP3 audio files are converted into a record. It’s a technical process called direct metal mastering that involves using a diamond stylus to cut grooves into a steel disc coated in high purity copper that correspond to a master recording (lower frequencies mean deeper grooves). Once the master is formed, it is plated in a pure nickel solution that ends with a “stamper” that serves as a negative of the metal master (it has peaks instead of grooves) and, will in turn, press out negatives of itself on vinyl.

One stamper is generally good for around 1,000 records, before it splits in the press or is worn out.

“The science blows my mind,” says Addezi.

Precision uses the DMM method over a more traditional lacquer process because it allows for closer grooves, enabling more music to bit fit on a side while also reducing the risk of surface noise.

The range of vinyl possibilities are endless in terms of colours (Precision has a catalogue of 48 base colours, including translucent, opaque, neon, and glow-in-the-dark options) and effects (splatter, colour-in-colour, stripes, marble, galaxy, clear), and using art and images directly on the vinyl.

Even the round shape can be changed.

“If an artist can conceive of it, we can do it,” says Addezi.

Precision is also constantly developing recipes for new designs and effects. That means scooping compound out of the washing machine-sized boxes it’s shipped in from a GZ plant in Tennessee and mixing new formulations in buckets. The mixes are then tested in automated presses.

The PVC pucks – soft blobs of plastic that will become records – are produced by GZ Media in Europe, as are the metal stampers and the compound, the rice-sized pieces of plastic that are melted into the vinyl to form colours and patterns.

GZ also produces all the print material, album sleeves, liner notes and posters that are packaged with the vinyl.

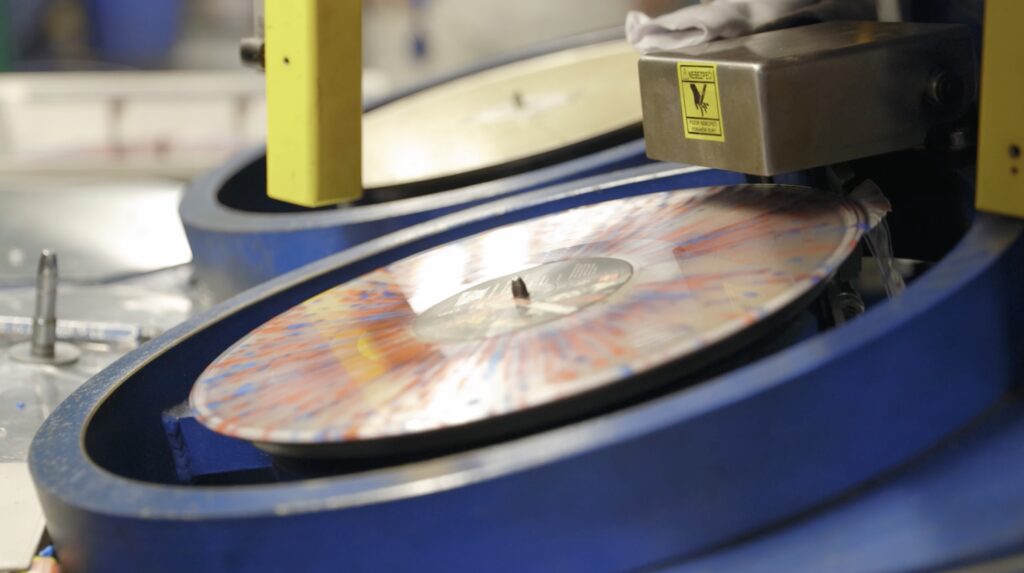

Precision has 25 automated presses that produce an LP every 23 seconds and five double-sided manually-operated machines for specialized pressings.

Stampers (one for each side of the record) are fixed to moulds inside the presses, where high-temperature steam and a literal tonne of hydraulic pressure squeezes the raw PVC into a grooved flat disc.

After a few seconds, the steam is replaced with cold water, which allows the record to become firm enough to be removed from the press.

The company takes quality control seriously. A bank of fully automated turntables and sophisticated audio software tests the production records against the masters, note by note.

“We can test eight albums at a time. No other pressing plant has this level of quality control.”

If an anomaly is found, records pressed before and after are tested. The search keeps expanding and affected vinyl is quarantined, until the issue no longer appears.

Sometimes it means cleaning the stamper or that there is a problem with the vinyl pucks or the compound.

It’s mesmerizing to watch an operator on a manual press take a puck of clear PVC and roll it in blue and red pellets, like an ice cream sandwich rolled in sprinkles. This is going to create a galaxy effect.

She takes a label for A side and B side (they’ve been pre-baked to remove moisture so they don’t split when pressed) and inserts the puck in between. She pushes a button and the press squeezes. She retrieves the record and places it on the “trimming turntable,” where excess vinyl is cut away to leave a smooth edge. Once cooled, it’s ready to play.

That excess material goes right back into the hopper to be reused and the vinyl goes into a tray that stacks into rolling towers. Those towers are shipped to Precision’s packaging and warehouse facility.

It’s a bright, sprawling place with rows of elevated shelves packed with boxes ready for shipment. Name a band and it’s likely you’ll find their albums stacked here somewhere. On any given day, about 80,000 records arrive from the pressing plant and about 35 shipments leave the warehouse.

Nearby, employees manage high-speed packaging lines. On this day, it’s Taylor Swift’s Folklore album being manually slipped into sleeves. It’s here that posters, stickers, liner notes, inserts with download codes and any other goodies are added before the sleeves run through a high-speed cellophane wrapping machine.

Precision’s operations earned it a Burlington Economic Development Corporation award for innovation and technology in 2019.

Addezi had spent a 31-year career with an automotive supplier when Isotope Music Canada founder Gerry McGhee asked him if he might want to head up a new record plant.

When he came to visit the location, Addezi couldn’t envision how producing records could ever fill the space.

“I remember thinking, ‘What have I done?’ There was a lot of anxiety about leaving a secure job.”

McGhee, who died of cancer in 2020, was the lead singer of rock band Brighton Rock. He founded Isotope in Burlington, and it is now Canada’s largest vinyl CD, and music DVD wholesaler with over 60,000 titles in stock. It specializes in both bulk and direct-to-consumer fulfillment for acts such as Elton John, Mark Knopfler, Blue Rodeo, Great Big Sea and Santana.

Addezi was born in Italy and came to Hamilton as a toddler. He grew up in the Barton and Sherman area before moving to the Mountain. He now lives near Mount Hope. He hoped to make a living as a musician as a young man during his time in all-Hamilton band The Rockers – before grown-up responsibilities beckoned – and he still has a recording studio in his house.

When the Precision opportunity came up, his kids urged him to jump in, even if it was a risk.

“This has been a great job for me. It’s a fun business to be in. Who doesn’t want to talk about music all day?”