PRIDE: Building a queer archive for Hamilton

The collection began with a posthumous donation of 50 years of materials in 2018 and the hope is to see that be a foundation for the inclusion of diverse and marginalized voices from across the 2SLGBTQ+ community.

The hope is to see a donation of archive materials from a Hamilton man working on the front lines of the fight for rights for gay men and lesbians in the 1970s and 1980s grow into a robust and comprehensive trove of local queer history.

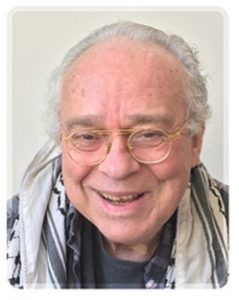

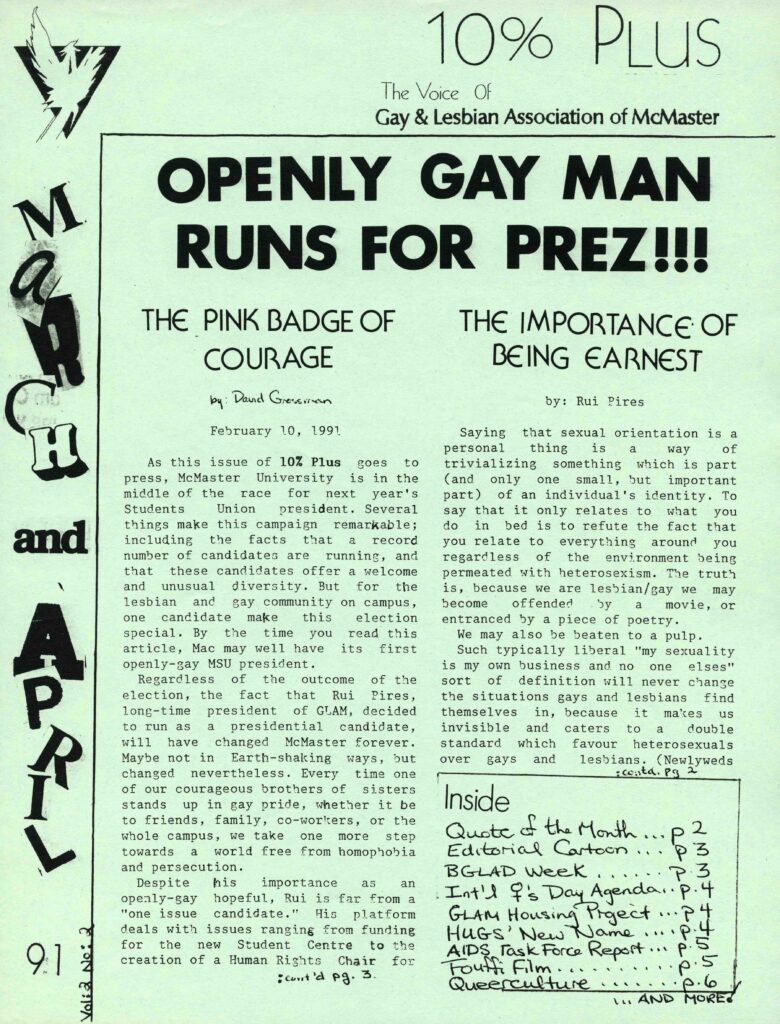

The estate of Michael Johnstone donated about 50 years’ and 50 boxes worth of materials to the Hamilton Public Library in 2018, including photos, meeting minutes, news clippings, newsletters and videos that he had collected, while “serving as a self-appointed archivist for a segment of the population that has long been marginalized,” says the HPL website.

HPL staff in Local History and Archives preserved and catalogued the materials to build the foundation of the Hamilton 2SLGBTQ+ Community Archives, which is giving researchers and the community the opportunity to learn more from decades’ worth of community-based activism and advocacy.

“What a visionary because after decades he still held on to all this material and then thought this needs to be preserved, and it needs to inform the future,” says Shelley McKay, manager of communications at HPL.

But the Michael Johnstone Collection is just the beginning. Many groups within the 2SLGBTQ+ community need to be better represented, according to researchers behind Building the Archives initiative.

“There has been much critique over the years for a tendency to archive histories and materials relevant to predominantly white gay (and to a lesser extent lesbian) lives, and for a subsequent lack of representation of more marginalized members of 2SLGBTQ+, including Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) 2SLGBTQ+, trans and gender non-conforming/non-binary community members, members who identify as mad or disabled, or those more recently added to the longer version of the LGBTQ+ acronym including intersex, two-spirit, and asexual community members.”

Image courtesy of Hamilton Public Library, Local History and Archives.

The goal is to learn from that struggle and to listen to marginalized communities in order to build an archive in Hamilton that is as diverse as possible, says Amber Dean, a professor of English and cultural studies at McMaster University.

“A big issue that has come up around gay and lesbian archives all across North America has been the fact that they’ve tended to centre around the records of white, gay men. And then, to some degree, white lesbians,” says Dean.

Johnstone was a graduate of both McMaster and Mohawk College who worked as a nurse at the Hamilton General Hospital for more than 25 years. Johnstone was heavily involved in the McMaster Homophile Association and the Gay & Lesbian Association at McMaster. He was also a founding member of the Hamilton United Gay Societies (HUGS) and heavily involved in the Hamilton AIDS Network for Dialogue and Support (HANDS) and the Hamilton Gay and Lesbian Alliance (HGALA) throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Johnstone died of lung cancer in 2018 at the age of 73. He signed papers making his donation official from a hospital bed.

“He had the brilliant memory of the things that happened 50 years ago,” says friend Cole Gately. “And he knew anybody who was anybody. And everyone knew Michael. He gathered all that history because he was a queer man in the community who took an interest and also got involved in organizing.”

The materials Johnstone amassed are now integral to a course created by Dean that examines the writings of Canadian lesbians and gay men, along with their art and activism from 1969 to 1989.

Fellow activist Mary Cahill, who began a friendship with Johnstone in 1975, says he was shy and reserved but unreservedly dedicated to justice and human rights. He lamented that he didn’t find the time to catalogue all the materials he had gathered and retained over the years.

“His big concern while he was dying was who was going to take care of it all so that the community could look back on its roots and the city could reflect on this part of its municipality history.”

Learning from the archive

Dean had been taking students for a couple of years to the ArQuives, the national LGBTQ2+ archives in Toronto, to research gender, sexuality, activism and resisting violence. When her friend Cole Gately got involved in the archives donation in Hamilton, Dean was so excited to have a local archive that she developed a new course that was offered for the first time in 2020.

“It’s basically a course on queer archiving. So the students read about theories behind queer archiving and why they matter as well as some of the LGBT history in Canada. We look roughly from 1969 to 1989 in the course. Which is great because it covers most of the period that Michael was collecting materials.”

Working with the archives has been eye-opening for students, says Dean, in terms of the number of queer spaces that existed in Hamilton in the ’70s and ’80s.

“There were more bars, more organizations and more overt political organizing than what exists now. there was a lot of challenging of police and policing of the community going on then. And there's evidence of that in the archives,” she says.

“Michael was a meticulous record keeper. And so he kept all of their correspondence and meeting minutes and things like that, of some of the early organization like HUGS, the Hamilton United Gay Societies. And so my students find that evidence and they're like, ‘Wow, stuff was really happening in those past decades. So it can be very eye opening for them.”

Among the many pieces of history is an open letter to police from a meeting of HUGS on April 1, 1981.

“What other reasons are there for special police attention to Dundurn Park or Jackson Street, aside from the fact that gay people sometimes get beat up there?” it reads. “Does the department invite representatives of a minority community to address officer cadets? ... If not, why not?”

Dean has her students write a reflection paper at the end of the course and many of them talk about the value of being aware of the history of queer and trans life in Hamilton “because they don't see a lot of visible queer and trans stuff happening in Hamilton in their present lives. And so it's both a surprise and a very affirming thing for them to discover this history.”

Image courtesy of Hamilton Public Library, Local History and Archives.

HUGS at one time owned a house that served as a community centre and ran a hotline from there called the Gayline. It was a evening phone line staffed by volunteers. All of the logs of that hotline are included in the archives.

“People who called in were really suffering and distressed. They wanted to know how to meet others or come out to their parents,” says Cahill. “We didn’t take community for granted because there was none. We had to build it for ourselves. We only had each other.”

Dean says students are amazed that resources such as these existed thanks to ordinary people making things happen.

“It just gives a really interesting look into that past and what was possible.”

The archives resonate in the present and can point the way to means to protect and advance rights today, says Dean.

“Archives are really useful for us in figuring out strategies, both what to do and what not to do. We can learn from the struggles that people had in the past and what causes organizations to fizzle out and things like that. I do find that sometimes young queer activists think that their generation is the first to have challenged the police scene of the community or the police involvement in community. And then it's very eye-opening for them to see that, oh, in the ’70s people were protesting in the police station or going to meetings and asking questions of police about why they’re harassing people around Dundurn Castle.”

The Michael Johnstone Collection is open to the public but it does mean a trip to the downtown branch of the HPL. The materials are not digitized.

A call for more voices

A series of virtual events in 2021 and a community workshop in 2022 started conversations about addressing the need to bring more diversity into the archive and more representation of marginalized voices.

Work is happening to set up an advisory committee that will reflect the diversity of the 2SLGBTQ+ community and to engage directly with trans people and BIPOC people in the queer community, says Dean.

“I'm hopeful that that helps keep the momentum going in terms of making sure that what ends up in the archives is actually representative of some of the diversity of our community.”

Those with a story to tell, can visit Tell a Story to submit information or a request that archives organizers get in touch with you. You can also contact Local History and Archives at HPL directly for more information about contributing material.

Another important part of the project is a series of oral history interviews attached to the archive. There have been 10 recorded so far. The hope is to expand that initiative, says Dean.

But another challenge is complexity around making these resources, along with student projects stemming from the archives, public and accessible while protecting participants from online harassment in a climate of growing intolerance and hate, says Dean.

Image courtesy of Hamilton Public Library, Local History and Archives.

Informing the future

Archives document the past but also play a big role in understanding the present and the future, says Gately.

“I am definitely a student of history. And I think it's very important. When I came out in the early ’90s, I started going to the Women’s Bookstop and I made friends with all these women who were older than me by maybe 15 or 20 years. And I basically sat at their feet, listening to them, listening to them telling stories, and I learned about the women's shelters and all the stress they were going through in the early ’90s. I learned about feminism, I learned about women's rights and about lesbians.”

Gately says there isn’t enough appreciation today for the battles of the past and how they can inform the future.

“Bad things happen when history isn’t understood.”

Cahill agrees. All the rights and freedoms enjoyed by the 2SLGBTQ community were hard-won and can be lost if they aren’t vigilantly protected. Queer history continues to be written and the archives needs to be a living, growing organism that reflects that.

“The one word that can never be in our vocabulary is complacent.”