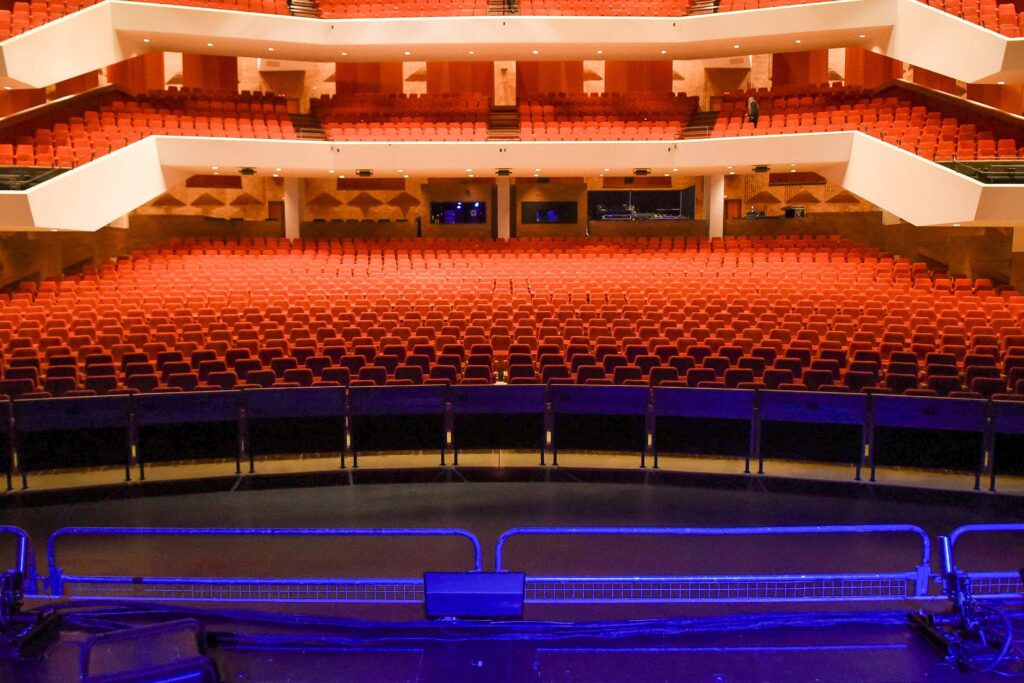

The marvellous Hamilton Place is 50

Yes, we know it’s officially called the FirstOntario Concert Hall, but its original name endures, as does its acoustical excellence, its musical legacy and its importance to Hamiltonians.

You might call it FirstOntario Concert Hall, because that’s what its sign says it is.

You might have called it the Ron V. Joyce Centre for the Performing Arts at Hamilton Place, though at 17 syllables, that’s a mouthful of a name.

Odds are, though, that you call it by its “maiden name.”

“If you've lived in Hamilton for more than five years, you still call it Hamilton Place,” says Andrew Nash, general manager of Core Entertainment. He’s right, of course.

For Hamiltonians, Hamilton Place is iconic. That’s only partially due to its unique concrete construction and 1970s appeal, with an exterior like an accidental retro-futurist/brutalist mash-up. It’s also because, from the start, Hamilton Place represented the city itself; the physical manifestation of our city’s long-beloved underdog-to-upset narrative.

As far back as 1912, Hamiltonians wanted a new, state-of-the-art, multi-use theatre, but it took us until the 1960s to make it a reality. That’s when a downtown development plan emerged, with a centrepiece originally envisioned as a theatre, athletic centre, space planetarium and national science and tech centre.

Hamilton Place was to be its cornerstone.

When both the provincial and federal governments declined to fund the project, Hamiltonians fought back by digging deep. The money came from City coffers, corporate donors, and donations from individuals. Hamiltonians made 16,000 to 18,000 individual contributions, raising over $3 million. The final cost was $10.8 million (over $75 million by today’s reckoning).

On Sept. 22, 1973, the 2,200-seat concert hall opened to the public. Inside, the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by the late Boris Brott, performed a piece penned for the occasion by Galt McDermot (the creator of the musical Hair). The late singer Salome Bey performed with the 64-voice Ontario Youth Choir. Outside, another 20,000 people partied to the sounds of Hamilton’s Crowbar and celebrated with fireworks.

Hamilton Place was, and to this day remains, a marvel of acoustical engineering, thanks to architect Trevor Garwood-Jones and acoustical consultant Russell Johnson. The theatre’s free-floating balconies were a key design feature, and most of the aesthetic choices – the cedar-clad acoustical shell, the depressed pyramid configuration of the bricks, the tapestries – are actually critical acoustic elements.

“The room would have been designed with pencil and paper,” says Michael Stewart. “We didn't have CAD programs back then. Here's a pencil, do the math, and give us the results. And they nailed it.”

Stewart’s father, Don, was the original head of audio at Hamilton Place. Today, Michael holds that title. To say he grew up at Hamilton Place is not much of an exaggeration.

“The building has pretty much stayed the same,” Stewart says. “It is built like a tank. There have been technical updates since I've been here – the new sound system, the line array, new consoles – but the fundamental acoustics still hold their own as some of the best. Roy Thomson Hall was designed and built years later, yet they've had nothing but issues with their acoustics.”

The HPO has been a resident of Hamilton Place since it opened. Music director Gemma New has worked in concert halls around the globe, and she, too, recognizes the distinctive qualities of their home base.

“There's enough space around you that you can be in your own moment but also have that profound collective experience, which is why we go to watch a live concert,” says New. “I love the space. I really think it's one of the best halls in the world.”

For New, it’s not simply the audience that benefits from Hamilton Place’s design. “For us as players on stage, it's such a beautiful place to make music,” she says. “In many other halls there are ‘dead spots’ where people can't hear other players on stage. We don't have that in Hamilton. People can hear each other, so they can play together more freely and comfortably, and we find these very intimate moments because of that.”

Back in 1973, word of Hamilton Place spread quickly among bookers, community groups, companies and entertainers. Inaugural GM George MacPherson worked along with the City and a board of directors to make the first season count, and though everyone expected it to run a deficit, the hall made a profit. Those pro-Hamilton articles appearing in Toronto newspapers over the last decade? They appeared in 1974, too, and Hamilton Place was always mentioned as one of the reasons Hamilton was on the ascent.

Photo: Lauren Kell Photography

The honeymoon was, naturally, short-lived. Problems and challenges – real, imagined, and invented for the purpose of creating a political football – began to arise. Ushers went on strike. Scandals abounded. Rental costs grew too high for community groups. The list goes on. As early as 1979, The Hamilton Spectator wanted to know: “Why isn’t it working out with Hamilton Place?”

In other words, Hamilton Place was just like any other concert hall, civic project, or business in Western civilization. Anyone who expected more was being unrealistic.

What hasn’t changed – even after hirings, firings, name changes and the eventual shift from public to private operation – is that Hamilton Place is still as impressive as it was on day one. Many of us, probably most of us, have been there in our lifetimes.

“It's been a meeting place for Hamiltonians since it opened,” says Nash, who became the GM of CORE in 2019 – just in time to struggle with the COVID-19 pandemic. The excitement of returning to the room, despite masks, bans on food service and the like, was palpable for him, the staff and the public alike.

“You can't replace that feeling of sitting in your seat and the lights going down,” says Nash. “The excitement building for the main act to hit the stage. Streaming, drive-in shows, they helped bridge the gap, but you can’t replace the live experience.”

Hamilton Place has hosted musical heroes, comedy legends, television programs, award-winning musicals, Netflix specials, fundraisers, and so many other things that compiling a list would be a pointless endeavour. What has set it apart, for Nash and many others, is the other stuff we take for granted, like dance competitions, recitals, graduation ceremonies. When we celebrated the life of Teenage Head’s Gordie Lewis, we did it at Hamilton Place. It is where we come together to be entertained, to entertain one another, to talk to one another, to take part in that profound collective experience that Gemma New talks about. There are few places like it and 50 years on, it’s still part of our collective experience.

No matter what we call it.

Hamilton Place celebrates 50 years almost to the day with the HPO’s Gemma New leading the orchestra in a celebratory season-opener “Gemma Conducts Schumann & Mendelssohn” on Sept. 23.

Memories of Hamilton Place

Graham Rockingham (former music editor with The Hamilton Spectator): “I’ve seen many great shows at Hamilton Place. Leonard Cohen before he took his comeback tour to stadium-sized venues. The Tragically Hip chose to perform back-to-back concerts there when they could easily have sold out Copps Coliseum. Wilco, Wynton Marsalis, Dianna Krall, the list goes on. Hamilton Place was always a gem, as good as anything Toronto could offer.”

Gemma New: “I always enjoy those Holly Jolly Sing-Alongs, where we bring up the lights. That has always been a really joyous occasion, singing at the top of our lungs at the holiday season. There was Holst’s ‘The Planets,’ and Mozart ‘Requiem’ with the Bach Elgar Choir and the Kitchener Waterloo Choir. There’s so many memories.”

Michael Stewart: “Gordon Lightfoot. Just to see him, it was so magical. My first show (as staff) was Henry Rollins doing spoken word. I remember doing soundcheck, how loud the monitors were. My knees buckled when I went up and tested his mic. I said Henry, ‘Are you deaf?’ And he kinda said, ‘Well, I played with a band called Black Flag, and I'm like, oh, right.”