The transformative potential of slower streets

Everyone wins when vehicles move at lower speeds and when pedestrian and cyclist safety is prioritized.

Sometimes transformative change comes from a major development or initiative. Few would argue the long-term potential something like light-rail transit will have on making Hamilton a more economically and environmentally sustainable city. However, transformative change can also come from smaller changes at a local level that, collectively, alter the nature of the city itself. This is the transformative potential of slow streets: the move to reduce traffic volume and speed so that people can walk and cycle more safely around their city. This global movement gained significant momentum during the pandemic, but some of the more notable initiatives, such as temporary street closures, were rolled back in recent years. This is unfortunate, as the benefits of slower streets are striking and worth considering as a fundamental part of community planning moving forward.

Why Speed Matters

In any talk of slowing streets down, the pursuit of safety is inevitably the instigator for change. In much of our work in community planning, speed is consistently cited as a top concern of residents for neighbourhood safety, and studies back this up. In 2012, Ontario’s chief coroner called for an overhaul of the province’s streets to bolster pedestrian safety, including suggesting many residential speed limits be lowered to 30 kilometres an hour. He made this recommendation after analyzing the circumstances of pedestrian deaths on Ontario roads. The review found that 67 per cent of the fatalities took place on streets with a posted speed limit above 50 km/h, while only five per cent occurred on roads with a lower limit. Similarly, an Edmonton study showed that at 50 km/h, 55 per cent of pedestrians will be killed, whereas, at 40 km/h, 25 per cent of pedestrians will be killed. Another study from the U.K. suggested that for every mile per hour reduction in average speed there is an eight per cent reduction in fatal injuries.

Researchers have dug deeper into this link between speed and safety and have found that vehicle speed impacts the driver’s ability to “see the road.” Essentially, peripheral vision narrows as speed increases. This link was illustrated through work by the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), which is an association of 96 major North American cities and transit agencies.

NACTO’s work showed that at 16 to 24 km/h, a driver’s vision is wide enough to see the full width of a streetscape, sidewalk to sidewalk. Full pedestrian activity is recognized, the distance required to stop a vehicle is about seven metres and the crash risk is 5 per cent. Increase speed to 32 to 40 km/h and things change. A driver’s peripheral vision is confined to the road itself, from curb to curb. This still enables recognition of pedestrians stepping off a sidewalk as they start to cross a road, as well as any flashing lights that might mark a pedestrian crossover. At this speed, stopping distance increases to 12 metres and the crash risk is 15 per cent. Moving to a speed of 48 to 56 km/h, a driver’s peripheral vision is further restricted. At this speed only the active driving lanes are fully recognized, which cuts off much of the surrounding activity/signals that would warn drivers of pedestrians. In addition, stopping distance almost doubles to 23 metres and the crash risk jumps to 55 per cent.

In a response to these studies, cities across Canada, including Hamilton, have started to lower speed limits to 40 km/h in some neighbourhoods. However, many arterial roads remain at 50 km/h, resulting in a variety of different speed zones that are not easily understood. We should follow the research and reduce speeds to the recommended limits in a consistent way so that everyone, no matter where they live, understands the rules – 30 km/h for neighbourhoods, 40 km/h everywhere else. In fact, Hamilton has already done this in the North End, so why not expand this to other neighbourhoods around the city?

Slower Streets Transform Neighbourhoods

Improved safety is not the only benefit of slower streets. When implemented at a neighbourhood scale, they have the potential to transform neighbourhoods and increase local quality of life. The ability to walk to local amenities, such as parks, stores, or schools becomes easier. This is good for physical health, as walking is an important activity for all ages and contributes to the ability to age in place. A neighbourhood study our firm Civicplan conducted a few years ago showed that the top location for neighbourhood physical activity was actually streets and sidewalks, ahead of local parks. This illustrated that rather than simply being routes to travel along, streets themselves are important public neighbourhood spaces alongside more formal recreational spaces.

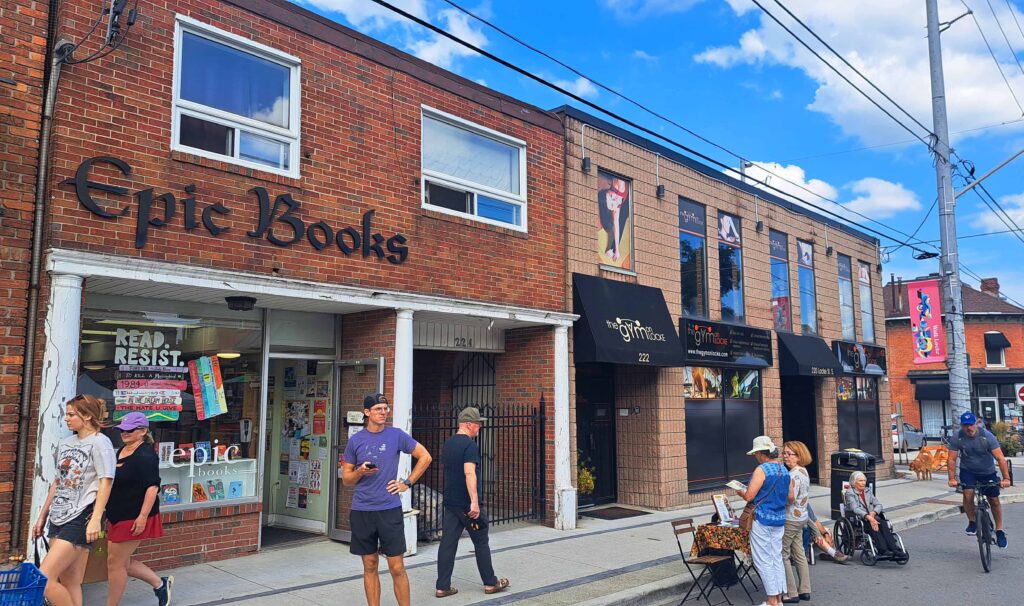

Walkability is also good for local businesses that depend on walk-in traffic. Just think of any vibrant commercial storefront clusters in your city and inevitably they are connected to customers by walkable neighbouring streets. In contrast, fast streets are rarely commercial destinations and are often underperforming economically.

Slower streets are even good for kids’ ability to learn since studies show walking to school has a positive relationship with school performance. Through the work of the Daily School Route (DSR), we know that the street environment has a major impact on walk-to-school rates across neighbourhoods and when surveyed, students and parents cite traffic safety as a major concern.

From a cycling perspective, many Dutch cities use slow streets as the foundation for their cycling networks. While higher capacity cycle tracks help people navigate busier streets, a slow neighbourhood street is the first or last step for cyclists to connect from home to nearby bike lanes.

Who Do We Build Our Streets For?

Embracing slower streets is really about asking some fundamental questions around city building. Specifically, who do we build our streets for?

For all the talk of “complete streets” and “walkability,” we still don’t view pedestrians on the same level as drivers when designing our transportation systems.

Consider the impressive level of thought around the design of the road network. It’s a complex environment with a myriad of interventions that help get vehicles safely in, through and around town. By comparison, pedestrians are a secondary concern, with less safe and efficient infrastructure.

For example, think of the last time you felt precarious while walking along a narrow sidewalk with a wall of vehicles rushing past you a few feet away. If a car were to approach a bridge, a guardrail would ensure it wouldn’t veer off the road. The guardrail is designed and built to keep cars safe. In contrast, pedestrian safety is ensured through a white line and/or a sidewalk curb. There is just no comparison. When you are on foot, you clearly get a sense of who the streets were built for. We are still at the point where a suggestion to reduce the number of traffic lanes to create a safer environment is met with pushback, even when it’s shown to have a negligible impact on vehicle travel time.

At best, vehicular convenience is treated on par with pedestrian safety and at worst it is prioritized. This is the fundamental roadblock to embracing the transformative potential of slower streets. However, if we can overcome this thinking, our neighbourhoods and our city will be collectively better for it.

Paul Shaker is a Hamilton-based urban planner and principal with Civicplan.