Think global, eat local

The pandemic exposed the failings of our global food system, writes Eugene Ellmen. Now, local food is having its moment, driven by a desire to eat better, support our farmers and fight global warming.

The COVID pandemic that gripped the world starting in winter 2020 was more than a public health crisis. It was also a food crisis.

Jars of tomato sauce and boxes of pasta normally overflowing from grocery store shelves were suddenly hard to get, along with basic food items like flour, canned goods and frozen meats and vegetables.

As global supply chains seized up, shortages sent many consumers into a panic, aggravating already long COVID lineups at supermarkets.

The experience shook many of us out of our food-buying complacency. A growing number of consumers now have an unsettled feeling that there is a better way to buy food than through multi-billion-dollar supermarket chains stocked with foods originating thousands of kilometres away.

“For the first time in a lot of people's lives, many of us had the experience of going into the grocery store and seeing bare shelves or some products not available,” says Tyson McMann, agri-food business consultant for the City of Hamilton. “I think it changed people's perception of where they get their food, how they get their food, and what that means.”

A recent McGill University study shows 77 per cent of consumers surveyed during the pandemic say they felt it has become more important to purchase food from local retailers than in 2019 before the pandemic. Sixty-five per cent of respondents also said they are purchasing more local food products than in 2019.

Sally Miller, manager of the Fair Finance Fund, a loan fund for Ontario farms and food businesses, says the pandemic accelerated an earlier trend for people to buy food online from grocery chains, small local grocers or direct from farms.

“I think what the pandemic did was to exponentially increase peoples’ tendency to buy online. And it’s really clear that’s a trend that’s going to go on happening.”

1,100 farms in Hamilton and Halton

For people who live in the Hamilton and Halton areas, the issue strikes close to home. A short drive from our downtowns and suburbs lies an agricultural region of more than 1,100 farms occupying about 190,000 acres. These lands are equal to about 140,000 football fields, and include some of the best farming land in southern Ontario.

This farmland is increasingly vulnerable to development pressure, an issue that has been in local headlines throughout 2022. It came to a head at the end of the year with the Ford government’s decision to open parts of protected Greenbelt lands to development, and to force the City of Hamilton and Halton Region to expand urban development on to formerly preserved agricultural land.

These decisions are expected to aggravate already huge recent losses of farmland. The Ontario Federation of Agriculture (OFA) estimates the province lost 319 acres of farmland a day in 2021 to urban development (up from 175 acres in 2016), the equivalent of nine family farms a week.

“Farmland is farmland,” says OFA vice president Drew Spoelstra, a farmer in the Binbrook area of Hamilton. “Once it’s lost to development, it’s gone forever.”

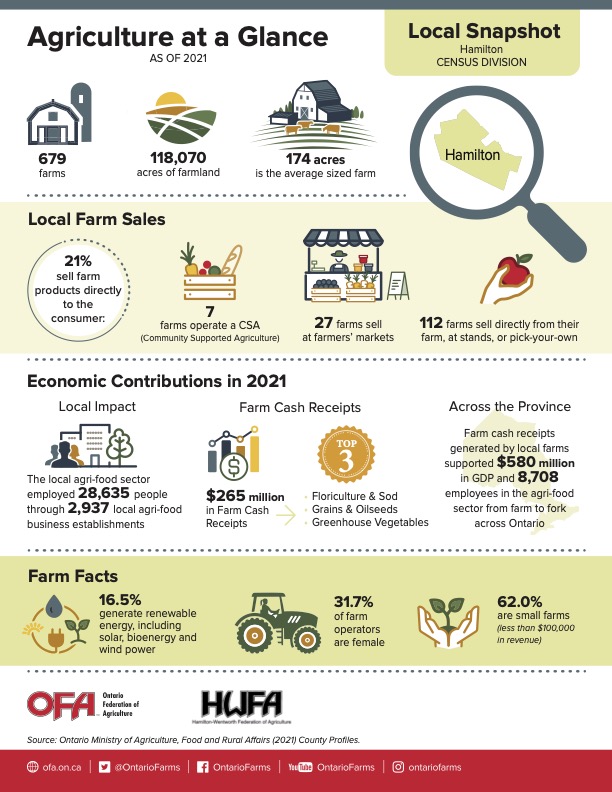

Along with the loss in farmland, farmers are also getting older, a sign of how hard it is for the next generation to enter the business. There were 679 farmers in Hamilton in 2021, down from 885 in 2011, according to the last census. In Halton, there were 431 farmers in 2021, down from 469 a decade earlier. The average age of Hamilton farmers is 58, up from 55 in 2006.

Farming has become more efficient and more technologically based, particularly for the export crops that dominate Ontario agriculture. About one-third of the farmers in Hamilton produce grains and oilseeds, grown mostly for export markets. The port in Hamilton is southern Ontario’s largest gateway for overseas exports of Ontario-grown corn, wheat and soybeans, handling more than a million tonnes of exports annually.

But a smaller contingent of farmers – about 140 or one in five Hamilton farmers – is striking out in a different direction. Rather than pursue national or global markets, they sell directly to consumers in the local area.

According to the 2021 census, more than 130 of these farmers operate on-site or off-site farm stores, stands, kiosks, U-pick or other farm-gate channels. About 45 make deliveries direct to consumers, and seven offer community supported agriculture baskets, which are bought by members who subscribe to the harvest of a farm or farms and receive baskets of produce throughout the season. Twenty-seven sell through farmers’ markets. Most sell through more than one system.

All these sales systems are expected to grow.

“I think there is an appetite for people to buy right from the farmer, pay a little bit more or sometimes pay the same amount,” says McMann.

The trend is partly due to the popularity of the 100 Mile Diet, the practice of eating foods produced within a short radius of where one lives. British Columbia writers Alisa Smith and J.B. MacKinnon wrote and published a book on the concept in 2007.

The diet offers health benefits by relying on whole fruits and vegetables rather than processed foods.

It also launched the idea of “food miles,” the concept that you can reduce your carbon footprint by eating food produced close to home. Some critics argue that CO2 is related more to food types than place of origin (with beef and pork much higher than poultry or plant-based proteins). Still, recent research bears out the importance of eating locally, with an estimated three billion tonnes of CO2 released annually in transporting food each year.

Miller expects local food production and distribution to become increasingly important, especially as arid regions like California struggle to maintain their agricultural exports in the face of dropping water levels, and droughts, and as wildfires and floods become more common.

“California agriculture is in crisis. Irrigation is drying up. Relying so much on exported food is really a model that is collapsing.”

Kierin Gorlitz, Gary Buttrum persevere at Hamilton Farmers’ Market

At its heyday in the 1920s, farm trucks, cars and horse-drawn wagons would jam bumper to bumper into an open lot at the Hamilton Farmers’ Market, the largest open-air market in Canada during the first half of the 20th century.

Among the regular vendors was Buttrum Family Farm, a founding family of the iconic market originally established in 1837.

The current farm owners – Gary Buttrum and Kierin Gorlitz – continue to keep at it and are still selling produce from their 15-acre farm at the market, making this an eight-generation family business.

Buttrums and Williams Brothers are the market’s mainstay farm vendors. Neither can survive selling their own produce exclusively, but their farms do supply the majority of inventory during the growing season.

The last couple of years have been tough as hybrid working arrangements have reduced the number of office employees downtown and customer traffic at the market has dropped.

Gorlitz and Gord Williams of Williams Brothers both believe the long-term future could be strong, however, as thousands of new residents move into nearby high-rise towers in coming years.

But the market needs to survive in the interim. For the next few years, Gorlitz believes the market should reduce the number of open days per week, so vendors can reduce their costs while supplying fresh high-quality goods at an affordable price.

“If you want convenience, you go to a grocery store or a convenience store, and then you compromise those other qualities. But the market has to be good. It has to be a special place.” hamiltonfarmersmarket.ca

Local-source grocery business Mrktbox growing quickly

A local-source Hamilton grocery business is growing fast through a combination of small neighbourhood stores and online delivery.

Justin Abbiss and his father Roger own Mrktbox Inc., which operates the Dundurn Market, Ottawa Market and Strathcona Market and online delivery service Bikeables. The business was included in the list of the top 100 fastest-growing businesses in 2022 in Canada by Report on Business Magazine.

Roger says the philosophy of the business is captured in the European bumper sticker, Eat Your View.

“The idea is that when you go for a drive in the country and you see all those beautiful fields, those fields will become houses and suburbs if you don’t support local food.”

Successful in the telecommunications industry, Roger turned his attention to the coffee and food business in 2011, founding the fair trade coffee company Coffeecology and partnering to establish the Democracy, Mulberry, My Dog Joe and Station Street cafés.

With Justin as CEO, the company established Bikeables for coffee and groceries in 2016 and the Dundurn Market in 2018. They opened the Ottawa Market in 2021, aided with financing from the Fair Finance Fund. In 2022, they moved into the former premises of the Mustard Seed Food Co-op, establishing Strathcona Market.

Justin estimates 75 per cent of his vendors are within 100 kilometres of the stores. One – Russell Ohrt of Backyard Harvest – is within a city block of the Strathcona Market.

Mrktbox has also been certified under the B Corp (Benefit Corp) program, one of the world’s highest corporate social and environmental standards. mrktbox.com.

Bringing the Milkman Back to Hamilton

A family of milk farmers has an audacious plan to bring back a service that hasn’t been seen in Hamilton for decades – home delivery of milk direct from the dairy.

Jennifer Howe and Ben Loewith, part of the Loewith family, which has been raising milk cows for three generations, are launching Summit Station Dairy this year. The plan is to revive home milk delivery with milk from their own 1,000-cow herd from their farm west of Dundas.

The plan is aimed at bringing back the tradition of home milk delivery, common in Hamilton and other cities until the 1960s when dairies switched to selling through convenience stores and supermarkets.

The Loewiths believe there will be interest in the new service because consumers will know exactly where the milk comes from.

“We have control of the process, right from what the cows are eating in the fields to how the cows are treated because all the milk is coming from our own farm,” says Loewith.

The dairy will be housed in a 10,000-square-foot building with a large glass viewing area where customers can purchase milk, cheese and yogurt on-site and watch how they are made.

It will be named after the former Summit Station of the Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo railway.

The dairy building’s architectural features will be based on the original station, which once stood across Highway 52 from the farm.

Milk delivery is scheduled to start in June and the dairy is expected to be open to the public this fall. summitstationdairy.com

Dave Loewith (Ben's uncle), Ben Loewith, Jennifer Howe and Carl Loewith (Ben's father) of Summit Station Dairy.

The new dairy is named after Summit Station, which once stood across Highway 52 from the farm.

A Food Basket Based on Ecosystem Balance

Chris Krucker stands by his field in mid-winter, surveying the landscape in front of him, barren of the vegetables, cattle, pigs and chickens that will bring life to this patch of Manorun Farm when the warm weather returns.

“Some farmers grow one thing, some grow three things,” he says. “We grow 30 or 40 things. We have everything that people need to eat for a full diet.”

Chris and his spouse Denise Trigatti have farmed this land west of Dundas for 30 years, committed to regenerative agriculture. In 2014, together with their four children who are now in their 20s, they planted about 2,000 native trees and bushes on their 20-acre farm.

Called an oak savannah, the concept is to use the trees to anchor soil in place and provide shade for livestock, which also fertilize the land. The trees attract birds, which eat the insects. And rain is funneled through swales, improving moisture content in the soil, disbursing nutrients.

Krucker and Trigatti sell produce through community supported agriculture (CSA) baskets, distributed weekly during the growing season. They include a wide variety of vegetables, made possible by the rich biodiversity of the farm. Meat is sold through an on-farm store.

The model has worked well for Manorun. CSA sales increased by about 50 per cent during the pandemic and the oak savannah has increased the farm’s environmental resilience.

“In a hot year, our hot weather crops do great,” says Krucker. “In a cold year, our cold weather crops do great. We don’t have to worry about a particular type of environment or weather knocking us out completely.” manorun.com

Eugene Ellmen writes on sustainable business and finance. He is also a volunteer loan reviewer for the Fair Finance Fund.