Turn up the music

Music education can enhance brain function and development, and as neuroscience research shows, has a long list of positive benefits for young people. Yet, music (and the arts) has been relegated to the back of the line of what is and is not important to teach today.

Human beings intrinsically identify with music from birth. It soothes, stimulates and invigorates our emotions. It can make us happy, melancholy, excited, energetic.

Music is universal. It’s what we do. We sing, hum, play an instrument, listen to a record or the radio, we dance or exercise or watch a live performance. It can help us go to sleep or wake up. Music helps us communicate. Music helps us bond. It enhances our learning process and teaches us to be empathic, collaborative and much more. But most of all, music brings people together.

Music has been part of our history for tens of thousands of years – both Homo sapiens and Neanderthal humans were creating music 40,000 years ago. Music is a critical component of every culture and civilization on planet Earth – past and present. It’s front and centre at family events, heritage celebrations. Music has been a cornerstone of Hamilton’s cultural fabric since the city’s founding. And in school, until recently, music was an essential part of learning and the school curriculum. Not so anymore.

Music and arts education in Ontario and Canada in general have been on the decline for decades. Ontario’s Mike Harris government (1995-2002) launched the initial assault in the late ‘90s: dropping Grade 13, firing unionized teachers, changing the curriculum and creating a “crisis in education” as Harris’ minister of education boasted at the time. And a crisis was indeed created and continues today.

Ignoring an extensive body of neuroscience research that links music training to a range of learning and behavioral development, the curriculum overhaul sidelined the arts and humanities. Music education options remain, but they are few and for the few.

The days when most if not all schools offered music courses, and had bands, orchestras and choirs are long gone in Ontario. School dances and concerts, which were a staple of student life until the 1990s, are history. Students get little exposure to a live music experience. In short, high school has become a drag for many kids. While the focus has moved to STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, mathematics), many scholars and scientists will argue the arts are just as important as STEM and perhaps more important in the big learning and brain development picture. STEM should be STEAM.

Neuroscience research

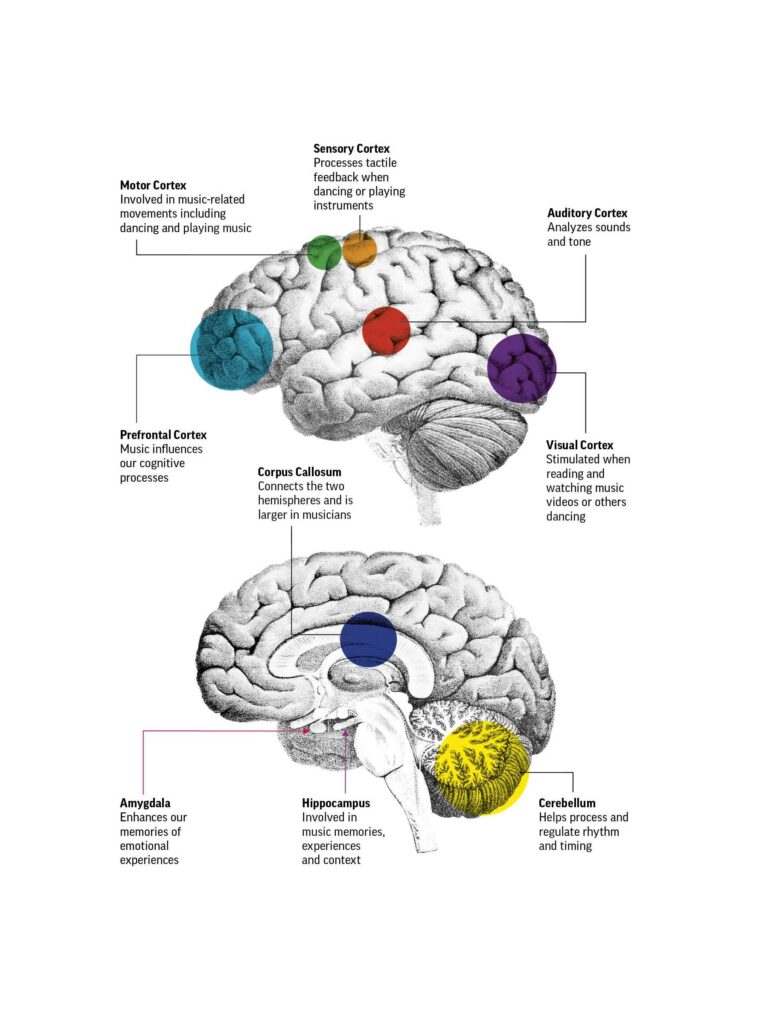

As one music lecturer put it, music is transformative, a super stimulant. Research on the relationship between music education and brain development has revealed a wealth of insights and important findings, adding to a growing body of evidence.

Neuroscience research has shown that music triggers and engages multiple regions of the brain simultaneously. Playing an instrument or singing stimulates areas responsible for motor skills, auditory processing and memory. Research at Northwestern University in Illinois revealed music improves the neural processing of speech, leading to enhanced language skills in children. A five-year study by University of Southern California neuroscientists reported music instruction appears to accelerate brain development in young children, particularly in the areas of the brain responsible for processing sound, language development, speech perception and reading skills.

“It’s the interaction of all the senses and the sensory motor interactions when you think about learning an instrument, it's very complicated,” says Dr. Laurel Trainor, professor in the Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour at McMaster University, and director of both the McMaster Institute for Music & the Mind (MIMM) and LIVELab. “You have to figure out all the motor movements. If you play violin, when and how do I move my bow? How do I control it to get a good sound? You have to listen to what you're doing. You have to be able to imagine in your head what you want the sound to sound like. It trains all kinds of things: executive function, memory, your motor system. And it makes your perception more acute.”

“Wellness, Well Played: The Power of a Playlist” by Jennifer Buchanan

Benefits of music education

Music education is shown to improve executive functions such as skills related to planning, decision-making, and self-control. Ontario’s People for Education, an organization founded to strengthen a universal public education system that graduates all young people with the skills and competencies they need, also identified the importance of an arts education in its 2018 report.

“Learning to play a musical instrument and the effects of music on critical thinking, spatial reasoning, and cognitive development; music helps build resilience, collaboration and a sense of community, and an education in the arts is a crucial component in the development of students’ cognitive, social, and emotional well-being.”

Trainor has been studying music’s impact on infants for about 30 years and points out that one of the most interesting things with psychology and neuroscience research is the role of music in infancy.

“Parents sing to their babies,” says Trainor. “The work shows that it's universal across every culture we've studied. Infants respond to music before they know any words. Parents use music to put them to sleep with the lullabies because they soothe. Studies show that music soothes and calms an upset infant. It focuses the infant's attention on the parent or caregiver’s face, on the sounds. It’s social engagement.”

Music brings people together socially – children, teenagers, adults. Often adolescents will express what social group they belong to through music.

“Music defines youth as people,” says Trainor. “It holds them together, bonds them as friends. They listen to the same music and are excited when something new comes out from an artist in the musical genre they like. I teach a course in the neuroscience of music, and when I ask the students in the course, ‘Why do you listen to music?’ The number one reason they report is they can feel emotionally connected. And I think the lack of arts and humanities and music in school has contributed to the growing mental challenges that kids have in high school today and going into college or university.”

Defunding the arts

The big challenges today for music education are funding and the positioning of the arts in the school curriculum. Budgets are as thin as they can be, and most schools have nothing to work with. Schools don’t have enough instruments, and many require repair and maintenance but there is no budget. According to Kristy Fletcher, president of MusiCounts, in 2023 Canadian schools on average received less than $500 a year for music programs – many have no money and must fundraise or go without.

Ron Palangio, retired instrumental music teacher and former head of arts at Cardinal Newman Catholic Secondary School, recalls the time when the school boards had a music consultant.

“That position was cut in the early ‘90s and music programs were left in the hands of local school principals. In the elementary schools, that meant there was often no one delivering music education other than schools which happened to have a music person willing to take it on. Budget was at the discretion of each principal. And I remember well the Mike Harris days when the war on education began … And that's exactly what he did. Students, teachers and schools are still suffering today from those horrible decisions.”

In 2021, the Coalition for Music Education released one of the most comprehensive national studies of music education in Canada. The report, “Everything is Connected: A Landscape of Music Education in Canada,” identified all the complex systems, structures, and elements that make up the current music education ecosystem. It documented official government policies affecting music education and surveyed the current reality of the administrators and K–12 music educators’ perspectives. Among the key findings were the inequalities in music education curriculum requirements across the country; and the inconsistent access to music education and resources including relevant and current curriculum, instruments, technology, equipment and materials.

The report painted a clear picture of the decline of music in schools. Out of a typical 1,500 minutes per week of instruction time, music education gets 4.4 per cent to 6.8 per cent of instructional time per week. The coalition’s report showed Ontario, Québec and Yukon are the only two provinces and territories without any mandatory music courses between Kindergarten and grade 12.

Ontario Music Educators’ Association expressed its concern about the dismal state of music education, and the steady and marked decline of identified music teachers in Ontario elementary schools. The numbers are beyond discouraging.

In 1998, only 58 per cent of Ontario schools reported having a designated music teacher. In 2007, the number of schools with a qualified music teacher declined to 48 per cent. By 2017, only 41 per cent of elementary schools had a specialist music teacher, either full- or part-time.

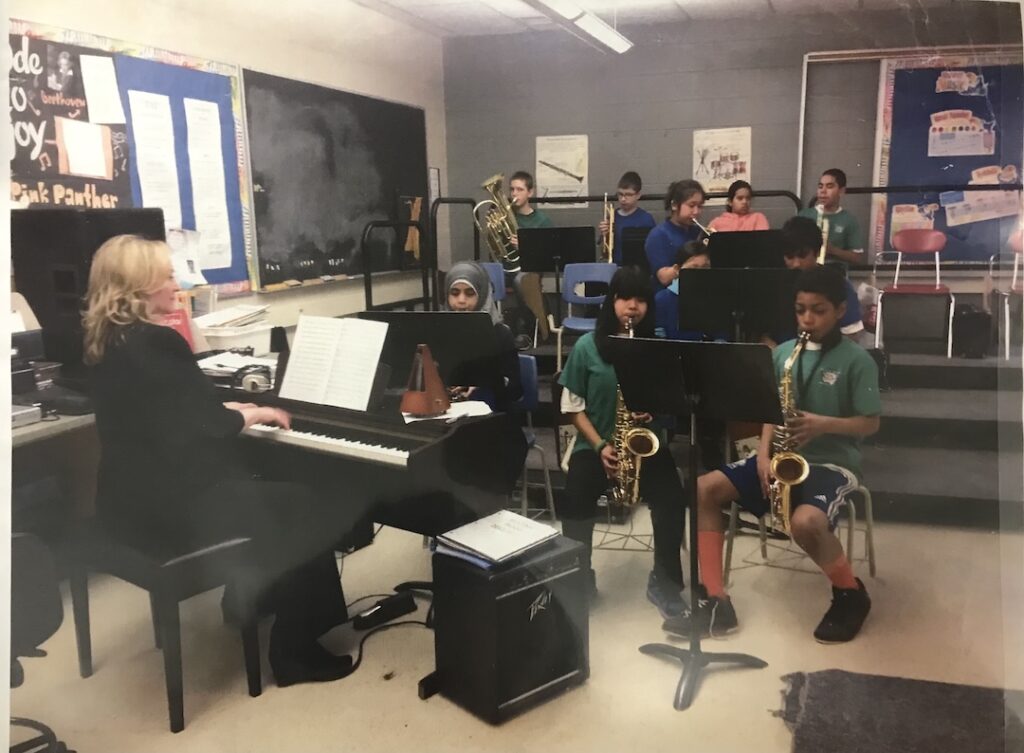

Nancy Minotti, an instrumental music teacher at Cathy Wever Elementary School, located in the lower city Gibson neighbourhood, recalls the days when music education was a vital component of the school curriculum.

“When I first started teaching, a group of music teachers from schools across the city would meet once a month after school. Someone would take charge of organizing the middle-school band, the festivals, the scholarships and the choir festival. We did that on top of our regular teaching jobs. And we didn't complain about that at all. It was all about the students. While the boards continue to support music in the schools today, budgets have remained unchanged for 30-plus years despite the rising costs of running an essential curriculum-based program.”

Not-for-profit organizations

To fill the funding void, schools have had to reach out to community and not-for-profit organizations for help with regular music programming, workshops and presentations. Volunteers have stepped in and tried to fill the arts and music void. Among the bigger players are Hamilton Children’s Choir, Hamilton Conservatory for the Arts, Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Hamilton Music Collective (HMC) through its An Instrument for Every Child (AIFEC) music education program.

HMC started working with schools in 2010 and has since engaged with 16 schools – more than 9,000 kids have gone through its programs. Success comes from the synergy between a professional artist or musician as instructors in the classroom and a teacher who can manage the class.

“Our program was always by word of mouth,” says Astrid Hepner, HMC program director and CEO. “We’d start in one school, then a principal in another school heard about our program and wanted it at their school. Ideally, I want to work with those schools where the principal makes an effort and is supportive.”

Hepner says it’s not about teaching a specific genre of music but getting an instrument in kids’ hands.

“When I was doing research for the program, I found there were a lot of instruments sitting in the schools, broken and not maintained, and that no one had the resources to fix them. There’s nothing more frustrating than an instrument that doesn't work properly. It defeats the purpose.”

Despite the challenges and lack of funding in music education, Hamilton is one of the most talented cities of musicality that he’s ever witnessed, says Tom Oliver, co-founder and president of the Hamilton Music Festival and Voice Concepts Private Studio.

“There are still pockets of music education excellence in Hamilton. Hillfield Strathallan has one of the best instrumental programs,” says Oliver. “Westmount and Westdale have music programs. And then there’s Glendale Secondary, which has the Program of the Arts.”

Glendale: Beacon of light

Glendale Secondary is a beacon of light for the arts and music in Hamilton. The public district school board’s Programs of the Arts at the east-end school includes an orchestral strings program open to all students in the city, a specialist high skills major in arts and culture, and an audition-based Program of the Arts. Altogether, the programs see roughly 300 students coming from all over the city and beyond. Half of Glendale’s 1,200 students are taking arts courses.

“In music, the program offers not only a concert band, but also an orchestra, stage band or rock band class,” says Paul Borsc, HWDSB Programs of the Arts coordinator at Glendale and head of music. “We have pop music majors. Students are not just taking them once, but rather take it in their subject area all four years. They might be playing a guitar and taking pop music as well as playing violin and learning how to play the flute. It’s diverse, challenging and fulfilling. We see our students walking away with a sense of accomplishment when they're done.”

The Glendale program reflects many of the options once available to students in high schools across Ontario. And while most middle and secondary schools struggle to get a single part-time music teacher, let alone someone full-time and qualified, Glendale is hiring its fourth full-time music teacher next year. It is the only school that has gone to a popular music focus.

“The range of private music study options is also growing all the time in Hamilton as there are more than 70 private studios in Hamilton teaching voice and instruments, and most are incredible,” says Oliver. “The lower the priority colleges and universities make music, the greater the demand for private teachers. The private studios are not cheap so the average family likely cannot afford it, so their kids lose out. And that is what we’ve seen happen as music was dropped from or minimized in the curriculum.”

Post-secondary offerings

The local music community has expressed great disappointment in two recent developments: Mohawk’s suspension of its three-year applied music program in late 2023 and McMaster University’s suspension of its music degrees this year. Despite McMaster’s music department’s notable history and past role in the city’s music community, prospective applicants will now apply for a bachelor of arts in music via the Department of Humanities and with no required auditions, suggesting the program will not include a performance element. Mohawk stated that its program was not financially viable due to increasing costs and declining enrollment, the latter likely a result of COVID’s impact on secondary school music programs.

“I was a champion for the music program at Mohawk mostly because I love music,” says the college’s past president Rob MacIsaac.

“The music program at Mohawk felt to me like one the most special parts of the school and I was always proud of the instructors and students. The fact that I had performed in a garage band with a bunch of my closest friends also played a role in my belief that actively engaging in music is a tremendously enriching experience. I started getting together with friends in a band relatively late in my life, but it taught me a lot about what an amazing experience it is to make music. I believe retaining and enhancing music programs in our education system is vital to creating well rounded, high functioning graduates.”

While Hamilton loses its post-secondary music options, several universities and colleges across southern Ontario are doing quite the opposite – expanding or launching new music and arts programs.

The University of Guelph launched a new bachelor of creative arts, health and wellness, bridging the fields of music, art and theatre with health care. In London, Fanshawe College offers a music industry arts program, focused on the business of music. At the University of Waterloo, many students taking music classes or participating in ensembles come from across the campus to complement their studies in math, engineering, health, environment, science, or other arts.

“Sheridan’s new bachelor of music theatre performance is the only one of its kind in the world,” says Oliver. “It offers theoretical and practical training in the core disciplines of acting, singing and dancing. We worked over eight and a half years to get the Ministry of Education to finally acknowledge and get the music theatre degree accredited. Sheridan is one of the most famous music theatre schools because of its live performance.”

The arts require a measured, increasingly nostalgic approach to learning, says Bob Shields, who taught music at Mohawk for 27 years and McMaster University for more than 20 years.

“They put relationship building first, which is a slow process. This type of learning has always been successful in the arts, but slow learning, face-to-face learning, relationship building, trust building, are secondary in this new transactional, high-speed, short-term education landscape. Education is increasingly about quick turnover, course compression, core skills and nothing else. So, if you’re an administrator and must make a decision: ‘Who’s going to get the space?’ ‘Who’s going to get the extra funding?’ With all the funding cuts, it’s a real-world bottom-line issue administrators have to make, and you can’t blame them for this. It’s the drastic funding cuts at Queen’s Park that started decades ago.”

But this shouldn’t be an either-or discussion. History shows that some of our greatest scientific minds were both artists and scientists. Louis Pasteur was a painter. Albert Einstein was an accomplished musician. Leonardo da Vinci was also an engineer, scientist and theorist.

Back to the future

Tom Shea, head of English at Saltfleet District High School, believes the problem for our society is we don't value arts and culture anymore except as consumers.

“Music has been, like so many other things, commodified,” says Shea. “We don’t value empathy, introspection or wellbeing. They’re not commodities and you can’t put a price tag on them. Sure, we can fiddle around with funding models and stuff, but until we, as a society, decide that the measure of a human is not tied strictly to their economic value, we're never really going to fix our education system.”

So, what can be done to reverse decades of ill-considered political decisions about music and arts education? Students have lost the chance to do better in their studies and their day-to-day lives, as neuroscientists have repeatedly found. They’ve lost opportunities that could’ve helped them manage the stress and turmoil of being a teenager in the 21st century and to help them better cope with the mental health issues plaguing young people today. There’s no doubt that reinstating funding of the arts is the starting point. And perhaps it’s time the arts be granted an equal seat at the STEM table when it comes to prioritizing and funding education.

Technology cannot replace creativity and imagination. Social media, online classes and the pandemic only fuelled the youth mental health crisis. Education must have some fun or school is simply a drag and kids will continue to turn to social media to fill the void.

In Northern Ireland, music is a statutory part of the arts curriculum until the age of 14. \

“If money wasn’t an issue or if funding could be re-routed, kids need to be taking music in elementary school,” says Borsc at Glendale. “It needs to be part of the curriculum. And it needs to be taught by people with a music degree, not someone signing a letter of agreement because they sang in choir or know how to play guitar. Music teachers must be qualified with recognized music education and music experience.”

Music education is a vital component of reaching adulthood, says Shea.

“Music in high schools teaches people how to be good citizens, knowing how to collaborate, co-operate and listen. They understand how to get along as they get opportunities to do collaborative and non-competitive group work, which is crucial to growing up.”

The advice and counsel of scholars, scientists and teachers are in unison. The arts, and music in particular, are important to a well-rounded education. And although the music and the message are playing loud and clear, bureaucrats and politicians are just not listening.

Community voices: Let the music play

Music can make a lasting impact on people’s lives – emotionally, psychologically and/or intellectually. Sometimes music can be life changing, other times it’s there to simply make you feel good. And the consensus on music education in Hamilton’s music community: music is vital for young people’s wellbeing, for their social development and coming of age, and vital for a balanced, stimulating education.

Lou Molinaro: Music promoter/talent buyer; instructor, venue management & talent buying, Durham College and Harris Institute; (and King of Fun!)

“Even though students can easily identify with music, it's much harder for them to participate today. Exposure is what’s missing. I noticed a change right away when they stopped hosting concerts at colleges and universities. And when I was in high school, we had dances and concerts with live bands, and many of them you’d recognize from listening to the radio. Schools had six, seven or eight live acts a year – that’s a lot of opportunities for local and regional bands to play and make some money. It helped us structure our social life too. So, when Mohawk announced it was closing its music program, it was a personal blow to me because at This Ain’t Hollywood, we’d host Mohawk music students to do live concerts. It gave them the opportunity to know the experience of performing live with an audience. And the shows were well attended. We need to bring back music programs at all levels, but also consider bringing live bands – dances and concerts – back into our high schools.”

Tim Potocic: Owner & president, Sonic Unyon Records

“I think music is critical to the development of being human. I think it's sad that it's been removed to the level it has been in the schools. I think the years from kindergarten to grade eight are the big development years. It's critical that music be put back into the school curriculum. It's ridiculous what has happened. Our administrators, government bureaucrats and politicians are completely missing the mark.

Some people in town are doing some amazing things in music education. The Hamilton Conservatory of the Arts, Hamilton Children’s Choir, Hamilton Music Collective. It’s fortunate there's people who are passionate about making sure kids get an education in music because the Ministry and school boards are not. As a city of music, we should do everything we can to bring that next level of artists up through the ranks. And that includes established artists in our community who need to outreach to young artists, and make sure we continue to nurture emerging artists because that is the lifeblood of the music community. And this is something we strive for very much in Hamilton.”

Alyssa LeClair: Actress/singer; graduate of NYU Steinhardt master of music program in vocal performance, music theatre

“It was the Hamilton Children's Choir that got me interested in music. In high school, at St. Jean de Brébeuf, we had an orchestra, a choir and musicals every year. And wonderful, musically trained teachers who were as invested in the music as they were invested in of getting us interested in it. I think the biggest thing about my music education is it's taken me so many places. In high school, I got to go to Spain, Poland and Sweden, and meet so many kids who are on the same level. Music builds compassion, community. It builds dreaming and pushes people to explore. I don't think I would've ever dreamed of going to New York University if not for having opportunities as a young person to sing in school. If I didn't get those opportunities or the encouragement, it never would've happened. I think requiring one arts course a semester should be as important as the required science or math per semesters to start. We have to re-start allowing school to be fun, to shape their brain, create higher brain function, to create connection and community. Just because a program doesn't have a specific ROI, doesn't mean that it’s not important to the bigger learning experience.”

Calvin Mulder: 3rd year student, Mohawk College applied music program, contemporary guitar stream

“I believe music had a lot to do with my improved performance in other subjects in school. The only factor that changed in the world around me was I started playing guitar. I was so obsessed with it and learning how to develop a skill and I was always learning. I'd come home and play for four or five hours every night. And it did something to me, and my grades went up from Cs and Ds to As and Bs. Music gave me a very clear sense of direction and purpose very early. I kind of knew what I wanted to do when I was 13 or so. And hey, if it isn’t a career in music, psychology or social science studies could be my back-up.”

Ash Hill: medic; music aficionado

“My only music experience playing in a band was middle school at Ryerson Middle School. I played in junior, senior and jazz bands. We were small, but we were good. Our music teacher was amazing. He had an ear for instruments, it was ridiculous. I was a trombone player in the band. We travelled for competitions and once played at Canada's Wonderland, which was so cool. I tried a few instruments, first the guitar but I found out I wasn't very guitar prone. I did some drums twice a week with Jack Pedler and tried the saxophone in music class. My teacher suggested I try something on a bass clef. ‘How about the trombone,’ and I just took off with it. It was fantastic. I loved it. There was no real finger action as all the muscle memory was in a spot. When we moved my new high school had no music program, so I turned my attention to lacrosse and volleyball.

Music gave me structure because I’d show up on time for band practice and go home practice more and more, on top of what you're already doing in school, whether it was homework or a school project. And regardless of whether you thought you’re going to be a musician or not, learning the instrument was just as important. Knowing that I'm not going to be a trombone player, but I still wanted to do it. And music is a big one when it comes to helping with stress. It doesn't matter what kind of music, whether it's classical or jazz, rock or blues, whatever it is, it helps you.”

Dr. Bob Shields: Professor of music at Mohawk College & McMaster University

“Shaped by the constraints of the current economy, music education, traditionally focused on music performance, is becoming increasingly focused on schooling students on producing music through the use of digital technology. The goal here is that the product can be exchanged for monetary gain, which aligns with the most college mandates centered on education for jobs, which in turn are shaped by the wider economic-educational imperatives of neoliberal governments. Among other things, this represents a linear deterministic approach to education and a transactional approach to relationships for learners. This current focus has had music programs scrambling to reimagine traditional performance and theory based post-secondary music education, requiring individual instrument lessons, music ensembles, and theory classes, etc. in response. However, maintaining a performance aspect to music education is a costly endeavour and requires physical space, which comes at a premium, and which has come under increased scrutiny.”

Ron Palangio, former head of arts at Cardinal Newman Catholic Secondary School

“At St. Thomas More, the school gave us a budget for music for the year, but both our principal and the superintendent at the time really wanted a music program. So, I was able to start a jazz band. I always did the choir and school plays. I supervised dances, judged student talent shows and fashion shows. I was involved in a lot of things in the school and just saw that as part of my job. I was at the school every night until six. But the government funding cuts domino-ed. With no music in the elementary schools and all the cuts, we had grade nine students who had little or no music at all in elementary school. The playing level diminished within two or three years. I saw a decline in quality and preparedness in music once they cut just a simple vocal music program in the elementaries. Before the funding cuts and the lowering of required credits in the arts, by grade 13, students were quite accomplished and if they were serious about music, they'd be prepared to go into post-secondary music. Not anymore.”

Tom Shea, Head of English at Saltfleet District High School

“I see kids trying to deal with existential dread. They see the world's going to be on fire by the time they’ve grown up. The economy's going to collapse. There's not going to be trees left. The wars and pollution and climate change, oceans are rising. That's a huge thing for a teenager or 20-something to carry around. And then there’s the cell phones and social media. They think they're connected because they're texting their friends but it’s not what human beings do. It’s just technology alienation. We've to also look at how the general social concept of education has changed. I got a master's degree in English because I just liked English. I just wanted to learn something. But now education is transactional, not relational.”

Malcolm Munoz Saravia, Mohawk Applied Music program student

“I decided to pursue music as a career when I realized three things: music heals, music unites and music shares. Music changed my life. It made me a better person, helped me cope with my problems and my unfortunate events. It made me connect with people better, made me learn more about the world, made me appreciate the “unimportant” things in life. It made me humbler.

Why is music so important to me? Just look at Powwow, look at national anthems, look at “Alright” by Kendrick Lamar, look at wedding dances, look at “Happy Birthday,” look at “Redemption Song” by Bob Marley, look at the Star Wars Soundtrack, look at Bollywood, look at “A Change is Gonna Come” by Sam Cooke, look at “Imagine” by John Lennon, look at workout music. If you look and then listen, you can understand why music is so important to me: Because it has been crucial to the world. Taking the [Mohawk] music program away may seem like a droplet to an ocean, but the seas have been getting dryer for the past years.”