Weird Science

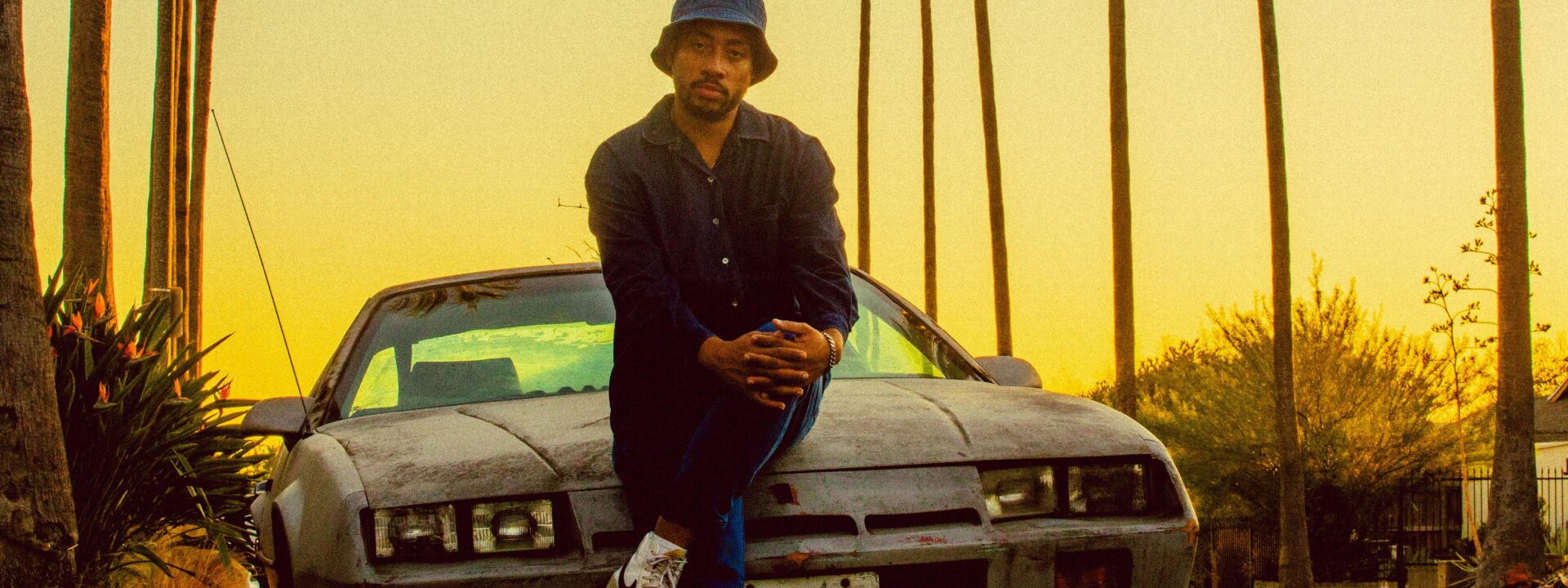

Rollie Pemberton, aka Cadence Weapon, has been turning heads in the rap game for years and recently moved from Edmonton to Hamilton. As Jamie Tennant discovers, when it comes to making music, the Polaris Prize-winning rapper can finally do what he wants, when he wants – and make it as weird as he wants.

Some people think Cadence Weapon is weird.

Back in the early 2000s, being a Black rapper from Edmonton was decidedly uncommon. Heck, anyone making hip-hop in Canada was, until recently, a bit of an outlier. A Canadian writing about hip-hop for Pitchfork? That was surprising. A hip-hop artist being named the Poet Laureate of Edmonton? Unheard of. Even Cadence Weapon’s music is unique – dynamic, ever-changing, influenced by a variety of sounds, often shot through with squiggly electronic brush strokes and eclectic vocal flows. Some people might think it sounds, well, weird.

Luckily, Canada is catching up to Cadence Weapon – or at least we’ve made great strides in that direction. There is plenty of great Canadian hip-hop. Young people have embraced stranger, more striking musical sounds. BIPOC artists are finally getting their due; in fact, in 2021, Cadence Weapon won the Polaris, one of the nation’s most important music prizes. Ultimately, he’s no longer all that strange.

So, he might just get weirder.

And why not? Cadence Weapon – real name Rollie Pemberton – has reached a point where he can do whatever he pleases. Not just because it will be accepted either, but because he’s in a mental and physical space where he seems to believe anything is possible. Which, of course, it is.

Pemberton grew up in Edmonton and knew early on that writing was one of his gifts. He excelled in English class, and he collected music and videogame magazines. “I’d read all the reviews,” he says. “Then I’d write my own and put them in the high school newspaper.”

When he began to make music, Pemberton took the lyrics as seriously as the beats. While he began to appear on stages in his hometown, he also began writing for local magazines, as well as the globally renowned website Pitchfork. He began making albums in 2005, toured frequently, and built a name for himself across platforms. Eventually, he relocated to Montreal where he became a sought-after DJ. In a way, he followed in the footsteps of his father, a hip-hop radio DJ in Edmonton for about 20 years. “I grew up in a library of music,” he says. “Hip-hop, funk and soul, R&B, rock music, everything.”

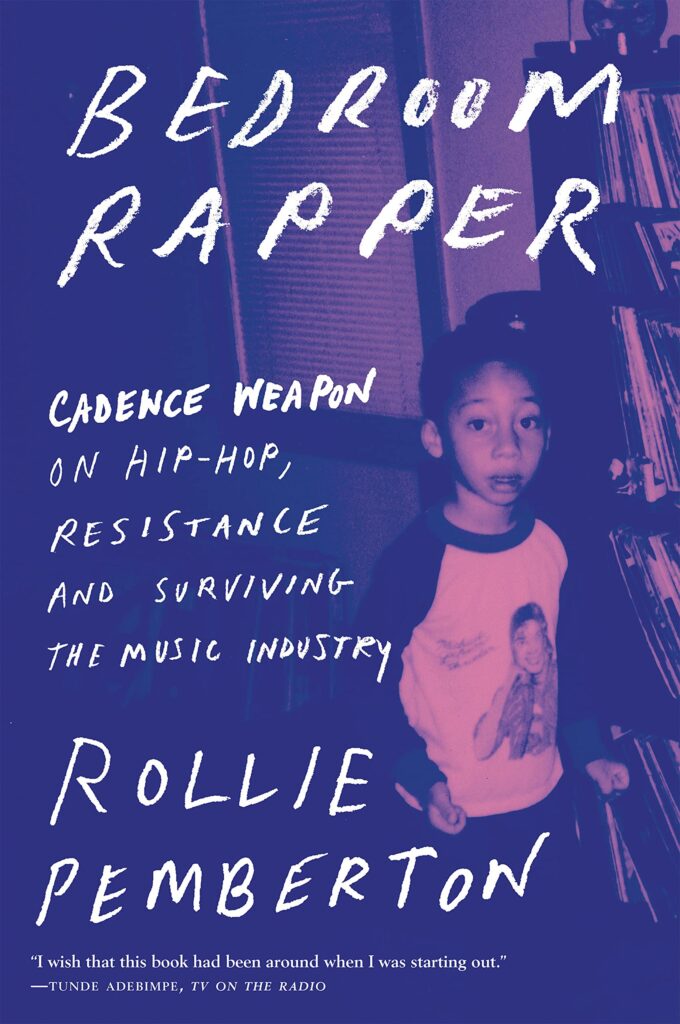

Years later, Pemberton relocated again, this time to Toronto, where he added “author” to his list of designations. In his memoir Bedroom Rapper, Pemberton covers a lot of ground, writing about his life, the history of certain genres of hip-hop, journalism, and his time as Poet Laureate of Edmonton, among other things. Naturally, he discusses his music career in depth and does not shy away from some of his most unfortunate experiences. In the book, Pemberton describes his struggles with his former label and management, which signed him to a deal that saw them take almost every penny the artist earned – even income that had nothing to do with music, like his Poet Laureate earnings – for years.

“Reliving that was the hardest part of writing the book,” Pemberton says. “(It was a) time when I was outwardly perceived as this successful person, but not getting any money from shows, no money from records sales… being exploited and feeling really trapped.”

Writing about those events was cathartic, he believes; putting it on paper took away the power of those difficult memories. Today, he has a new label, new management, and even a new city. In late 2022, Pemberton and his spouse relocated to the east end of Hamilton.

“Over the pandemic we were somewhat obsessed with the idea of moving to Hamilton,” Pemberton remembers. “We would come here, stay in an Airbnb, and pretend we lived here for weekends. It felt so hip and interesting here. I think it really suits us. We’re very working-class people, and it reminds me of Edmonton. I like being in places that have that emerging energy.

“It feels like people like it the way it is,” Pemberton continues. “They know what’s special about it here, and they wanna fight for it. They don’t wanna be Toronto. Developers see cities as an opportunity to make more money instead of seeing an opportunity to make life easier for people who live there. That’s the way it used to be but it hasn’t been that way for a long time. Hamilton reminds me of Toronto 15 years ago.”

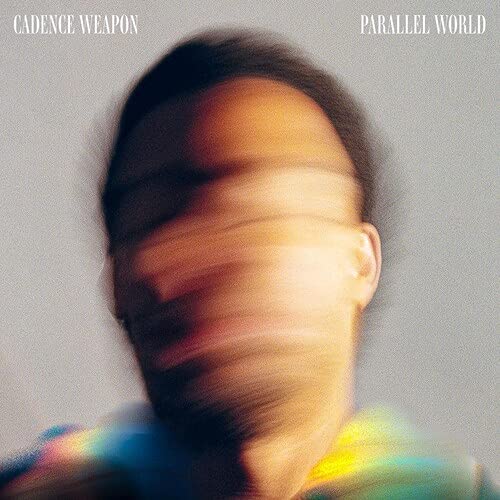

Pemberton addressed the situation in Toronto on the track “Skyline” from Parallel World. Indeed, politics and activism are common in his music. Not just his music, though – also in the rest of his life. Consider last autumn’s Toronto Life article, which went viral, in which he explores the difficulties artists face in today’s climate.

“I noticed musicians everywhere were cancelling tours,” Pemberton recalls. “I played a bunch of festivals this summer and it went very well, but I couldn’t believe how expensive things had become and artist fees weren’t balancing it out. I got hit hard with merch cuts. So the Animal Collective or Little Simz cancel tours. Little Simz can’t do an American tour? The most accomplished, successful artist in England? When we’re in a position where our most talented and successful artists can’t afford to play shows, there’s something wrong with the system.”

Pemberton took action on one issue in particular. He joined forces with the Featured Artists Coalition (FAC) and the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW) for the #MyMerch campaign. Merch cuts – where some venues demand a percentage of merchandise sales at each show – can make the difference between a successful tour and one that actually costs the artist money.

“I just want it to be as equitable for everyone,” he says, “and I don’t want the artist to be the one that suffers the most.”

Today, Pemberton’s artistic career is no longer hemmed in by bad-faith business deals, no longer stymied by an anxiety-inducing city, no longer side-eyed by people who haven’t a clue where he’s coming from. Mind you, there has always been respect for his work in certain circles. Every Cadence Weapon album to date has at least been long-listed for the Polaris Prize. He did not win, however, until he won for Parallel World. “Sometimes I felt like I wouldn’t win because I wasn’t a white indie rocker,” Pemberton says. “Now we’re into this wave where it’s a lot more diverse.”

The Polaris was more than just a cash infusion, although the $50,000 prize was greatly appreciated after Pemberton’s prior business tribulations. The Polaris means much more to him than that.

“Now my name’s up on that list,” he says. “Me and Buffy Ste. Marie and all these legendary artists. I’m a part of history and it feels good. I love to be in a position to just make what I want. I can get as weird as I want.”

What You Need to Know

NAME: Rollie Pemberton aka Cadence Weapon

BORN: February 1986 in Edmonton, AB

KNOWN AS: emcee, producer, journalist, author, poet

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Bedroom Rapper: Cadence Weapon on Hip-Hop, Resistance and Surviving the Music Industry

ON WRITING BEDROOM RAPPER: Initially, writing a memoir was not part of Pemberton’s plans. “I was writing a work of fiction inspired by my experience being a DJ in Montreal,” he says. “I read a chapter of it at this festival in Edmonton, and my friend said ‘Oh, that was really great but why don’t you just write about your career?’ And I was like damn, maybe I should.”

ON HIS INFLUENCES: In Bedroom Rapper, Pemberton delves deep into his musical influences and elucidates on genres that were formative for him, such as trap and grime. Hip-hop, however, is far from the only genre that influenced him. “I never thought, ‘Oh I’m Black, so I can’t listen to Gary Numan,’” Pemberton says. “People would be shocked to know some of favourite stuff is Depeche Mode, Pet Shop Boys … that’s what’s really influencing my next album. All this ’80s synth pop. People wouldn’t assume that I’m into that. In this day and age, we ought to get beyond those preconceived notions of what people listen to.”

DISCOGRAPHY: Breaking Kayfabe (2005), Afterparty Babies (2008), Hope in Dirt City (2012), Cadence Weapon (2018), Parallel World (2021)