AGH celebrates 110 years with Directors Collect

The exhibition is a polyvocal mixtape that explores the priorities of the Art Gallery of Hamilton’s six directors and their contributions to the gallery’s collection. “Director’s Collect: 110 Years” runs until Jan. 5, 2025.

The Art Gallery of Hamilton began from a donation of paintings to Hamilton city council two years before the establishment of a public art gallery in Hamilton, which makes “Directors Collect: 110 Years” a somewhat tongue-in-cheek title for the AGH’s anniversary exhibition – this is, after all, a collection 112 years in the making and long predates the existence of any director.

While collections are guided in large part by the vision of an institution’s leader, they are built by many hands and shaped by any number of external influences, from a too-good-to-miss opportunity to the generosity of private donors.

Curator Tobi Bruce sums up this project in more succinct terms: “Institutions are human.” “Directors Collect: 110 Years” celebrates individuals and their stories by inviting the six directors who have sat at the helm of the AGH to share their personal selections of works acquired during their years at the helm.

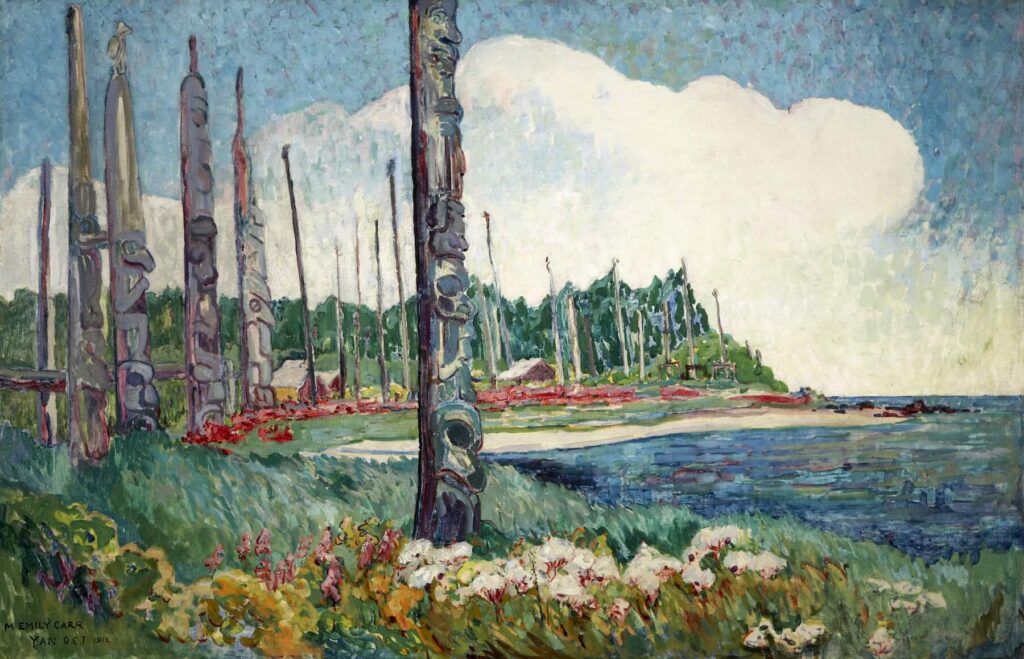

The first among these is Thomas Reid (T.R.) MacDonald, whose curatorial voice is represented by his daughter, the painter Katherine MacDonald. An artist himself who served as the AGH’s director and curator for its first 26 years, T.R. MacDonald built the foundations of a collection that would help establish a canon of Canadian art grounded in the Group of Seven and the Beaver Hall Group, while also collecting essential European artists of the 20th century and Japanese printmakers.

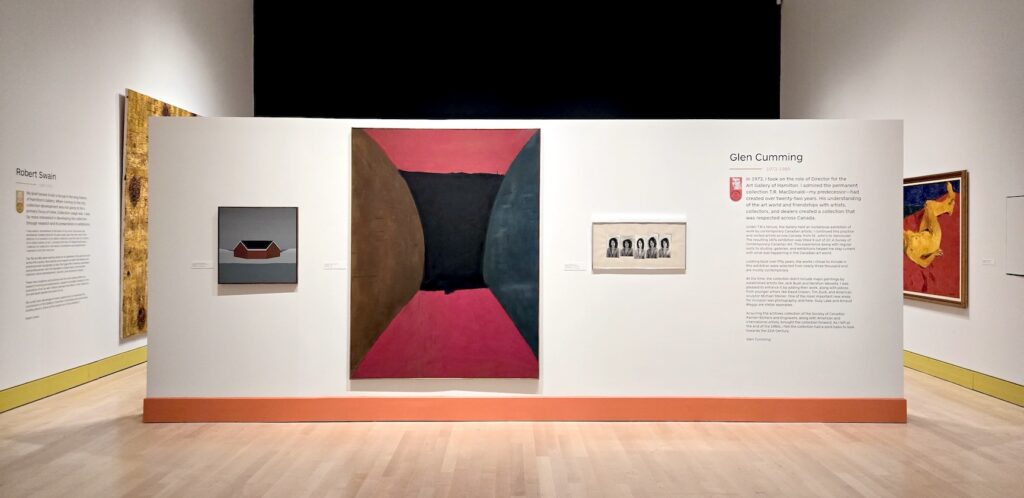

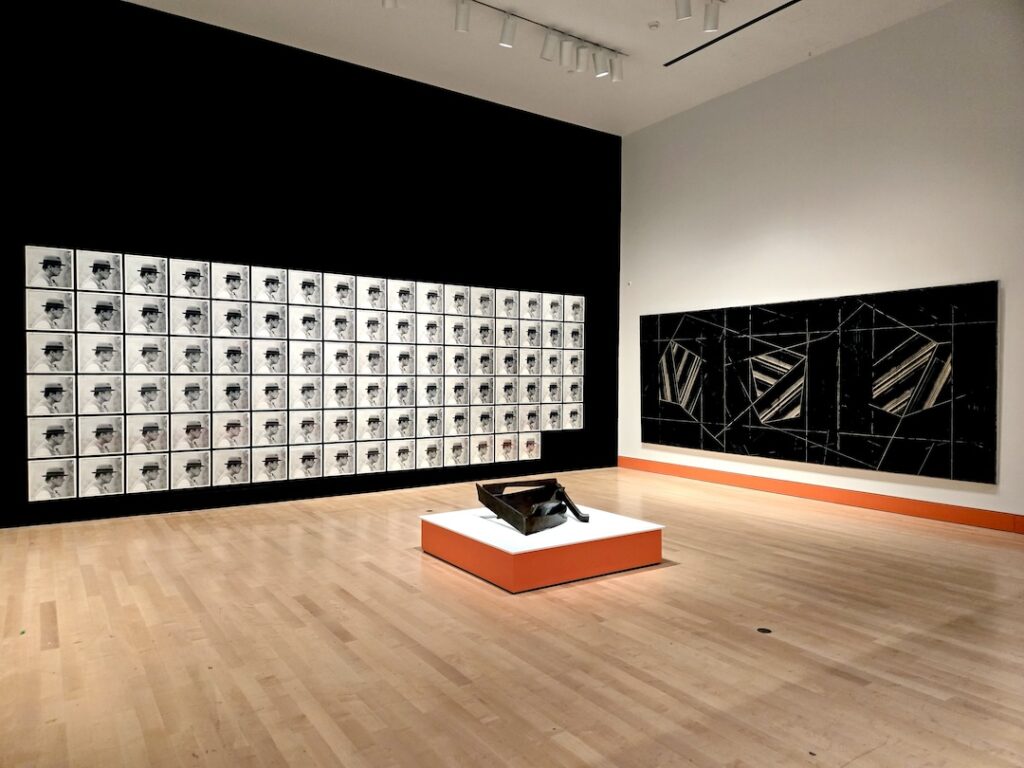

In his successor Glen Cumming, the collection took a contemporary turn towards the leading artists of his day such as Arnaud Maggs and Suzy Lake, who recalls Cumming as among the first to place her work in a public collection. Robert Swain’s relatively short tenure from 1990-1991 receives recognition here with exclusively Canadian selections including Lynn Donoghue’s totemic Four Tradesmen, and marks the end of the hyphenate role of curator for AGH directors.

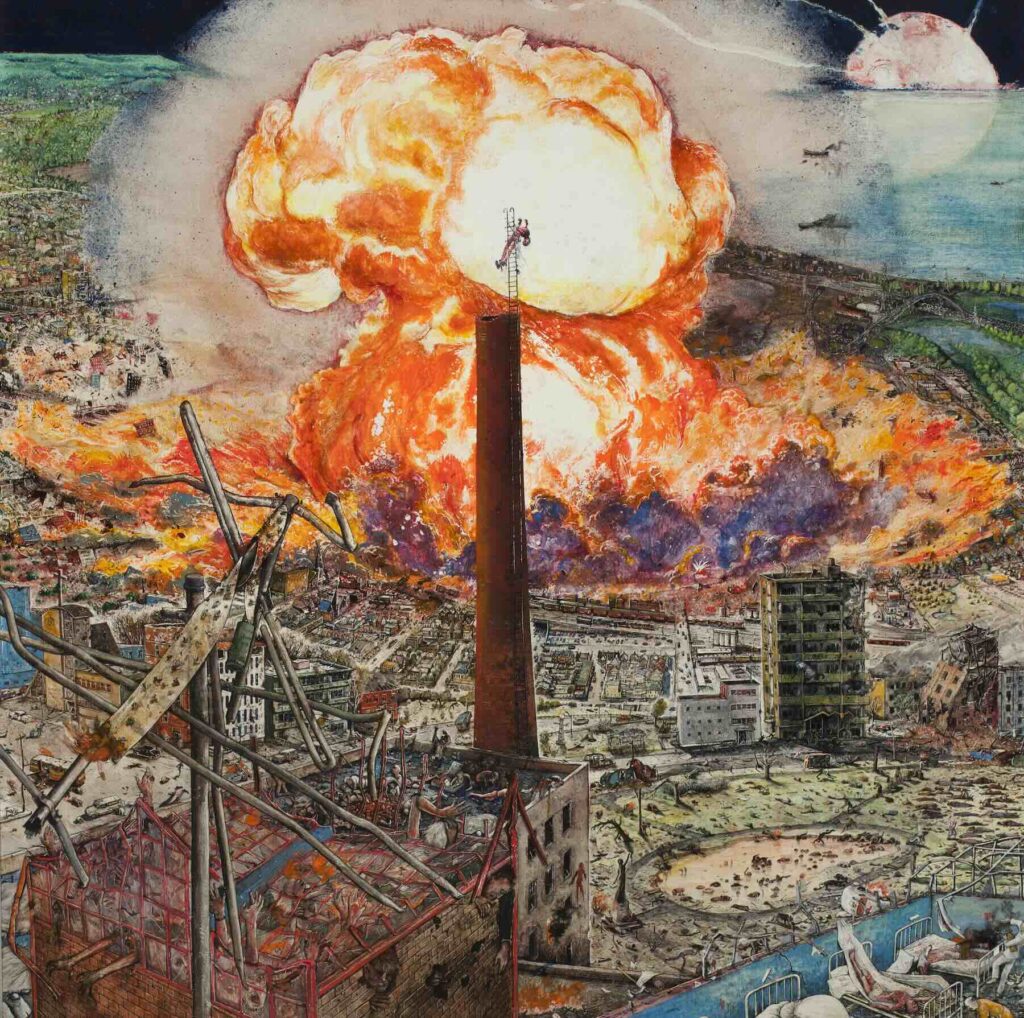

Ted Pietrzak became director at a time when the AGH was facing more challenging economic times. Working alongside then-curator Ihor Holubizky, Pietrzak focused on building strength in the contemporary collection with iconic works by John Scott, William Kurelek, and the flashing lights of Micah Lexier’s Self-Help, a work that is among the first installations acquired by the AGH. The arrival of Louise Dompierre in 1998 marked an era of renewal seen in a large-scale renovation in 2005 and the remarkable donation of the Tanenbaum collection of European paintings and sculptures. Dompierre’s selections emphasize the virtuosity and beauty found in this gift with masterworks that clash deliciously with the brash gestures of Pietrzak’s selections in the same gallery.

These contrasts are very much the point of “Directors Collect,” which heightens the aesthetic differences between its six directors in sometimes pointed ways to reveal the human heart of collections and make visible the global shifts in art and ideas that have unfolded in the past century. In addition to resisting the impulse to maximize the number of works on display, this polyvocal mixtape of an exhibition allows the tensions between its authors to speak to priorities and perspectives that have evolved over time. The role of directors, in current director Shelley Falconer’s view, is not to disavow disagreements with history but to build a tent large enough to hold these conversations: “You don’t learn at all if you don’t understand history.”

With Falconer’s selections, “Directors Collect” enters the 21st century in both its artists and ethics. Contemporary Indigenous artists like Carl Beam and Meryl McMaster are powerfully represented here, as are works by Hamilton artists Kareem Anthony Ferreira and Nathan Eugene Carson. Edward Burtynsky, whose large-scale photographs of staggering industrial scars on the land had their foundations in the steel mills of Hamilton and Niagara, is included here as well in further recognition of the local stories found within the collection.

Raising awareness of the AGH’s collection is central to Falconer’s current mission, and rightly so. This is a vast cultural asset of more than 11,200 works of art held in the public trust that are widely respected on the national stage yet seldom thought about by the average Hamiltonian. Falconer has been determined to connect Hamilton to its collection since taking the helm in 2014, first by encouraging local school boards to schedule more field trips to the AGH rather than Toronto galleries and museums so young people in the city can build an early familiarity with the exceptional art held in their own civic collection.

Another of Falconer’s selections for “Directors Collect” comes from the Chedoke Collection of soapstone carvings by Inuit tuberculosis patients who created these works while hospitalized in the former Mountain Sanatorium from 1953-1963. These carvings are a testament not only to Inuit ingenuity but Hamilton’s role in treating a major epidemic of the mid-20th century. Shown here alongside three photographs from Barry Pottle’s Awareness series of “Eskimo identification tags” issued by the Canadian government to Inuit community members as mandatory identification numbers, this dual display provides further insights into a complex history that the AGH collection is uniquely able to illuminate.

The purchase of the Chedoke Collection was made possible by an anonymous donor who stepped in to ensure these historically significant works would remain in public hands. This is one example among many of the people beyond these six directors who built Hamilton’s collection. Behind every acquisition is an unseen team of advocates, carers, and donors who move mountains to keep art accessible for present and future generations. The passions of those individuals reverberate through the collection in ways that capture something deeper than their names.

As Falconer notes: “It speaks to the history of Hamilton.”

Directors Collect: A sampling

Emily Carr, Yan Q.C.I., 1912. Photo: Mike Lalich

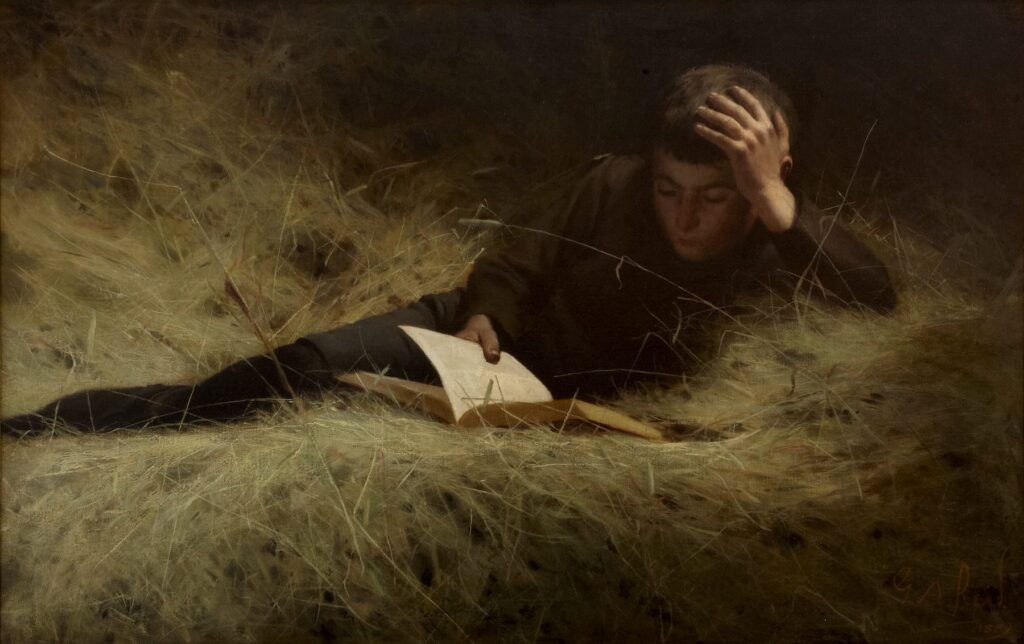

George Agnew Reid, Forbidden Fruit. Photo: Mike Lalich

Edward Burtynsky, Nickel Tailings #36, Sudbury. Photo: Courtesy of the artist

Lawren Harris, Ice House. Photo: Mike Lalich.

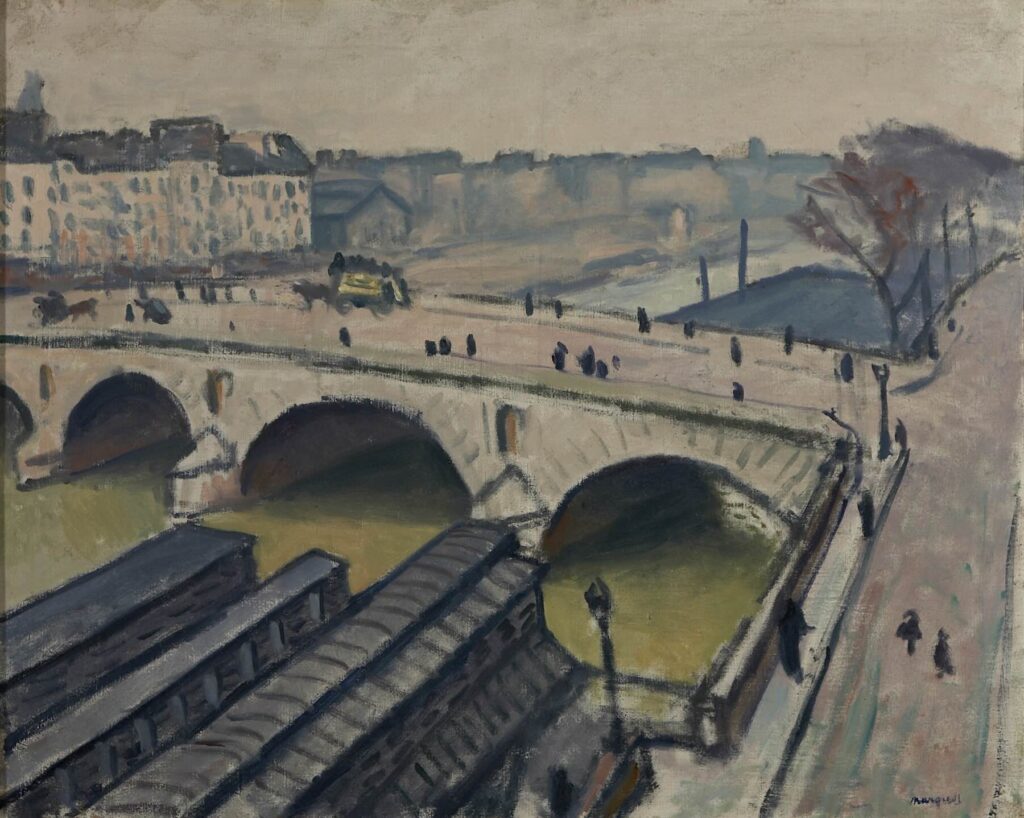

Albert Marquet, Le Pont Marie vu du quai Bourbon. Mike Lalich

Julian Ruggles Seavey, Raspberries. Photo: Mike Lalich

Bertram Brooker, Symphonic Forms. Photo: Mike Lalich

Luca Giordano, The Massacre of the Children of Niobe. Photo: WaveLength

William Kurelek, This is the Nemesis. Photo: Robert McNair

Kenojuak Ashevak, The Owl. Photo: Mike Lalich

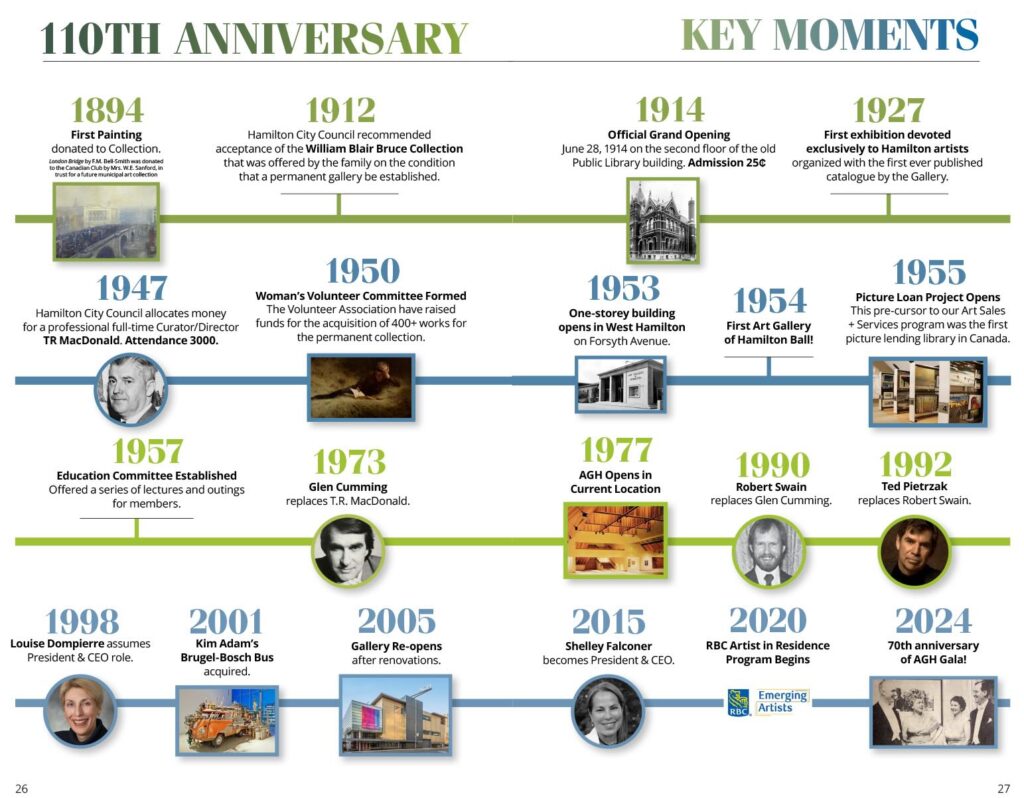

AGH: The history

On Jan. 31, 1914, the Municipal Gallery of Hamilton was incorporated with an annual budget of $1,000 for its operation, maintenance and collection. It officially opened its doors in June of that year with an inaugural exhibition of paintings donated by the widow of Hamilton-born artist William Blair Bruce (1859-1906). The donation came with the proviso that an “appropriate venue” be found to house the works.

The AGH was initially located in five rooms of the Hamilton Museum that was housed in the disused Hamilton Public Library Building on Main Street, just west of James Street. It wasn’t until 1947 that the City allocated enough money to pay the salary of the first staff member. That was Thomas Reid (T.R.) MacDonald, the AGH’s first curator-director and he served in that role until 1973.

The AGH moved into its second home on Royal Botanical Gardens land near the Sunken Gardens in west Hamilton in 1953. It was a one-storey Art Deco-style building with exhibition space totalling 10,000 square feet.

Then in 1969, architect Trevor Garwood-Jones was commissioned to design a building for the AGH that would be part of the downtown urban renewal project called the Civic Square. That building, at 123 King St. W., opened in 1977 and was extensively refurbished 20 years ago.