Artist Chris Myhr makes a Salient point

Hamilton artist's mid-career retrospective at the McMaster Museum of Art celebrates his ongoing fascination with water’s contradictory nature.

Chris Myhr thrives on contradictions: he is an artist whose methods look a lot like science, a digital photographer fascinated by the raw, earthly substances found beneath his feet. His sleek, precise images are shaped by the natural inclinations of land and water – especially water, which will always flow by its own will.

Salients, Myhr’s mid-career retrospective on view this winter at the McMaster Museum of Art, collects the clay pipes of seafarers and grotesque lumps of industrial waste washing up from the Great Lakes as evidence of our uneasy relationship with water. An experienced diver who recalls being hypnotized by Halifax’s harbour during grad school at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Myhr has a life-long fascination for water. This attraction took a dark turn with the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami – as the spouse of a Japanese person who once lived in that country, watching media coverage of “this dark column of water” carrying buildings and lives away hit horrifically close to home.

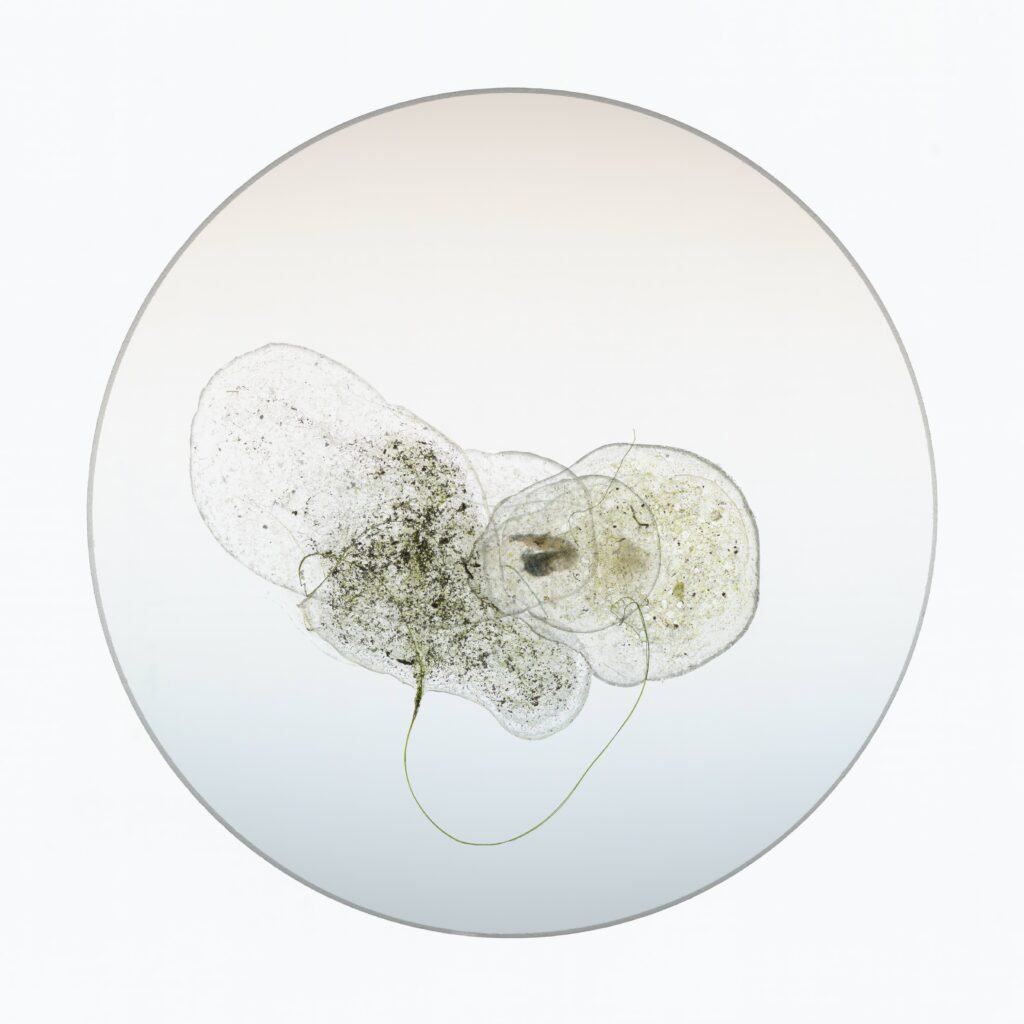

Suspensions (Untitled #9b) Photo: Chris Myhr

Suspensions (Untitled #10b) Photo: Chris Myhr

The tsunami was a revelation of water’s contradictory nature. Life cannot exist without it, yet water is also capable of unpredictable devastation. That tension is visible in Myhr’s Vessels: Undertone series, featuring glass vessels pulled from the Atlantic seafloor by Halifax diver Bob Chaulk. Startling blue chemical reactions and etched lines show the passage of deep time sunk in the sediment, while the once-exposed surfaces crawl with lively spores and shells.

While water can consume whole ships and reduce metal to dust, glass and ceramic are uncannily immune to decay. Salients includes many images of clay pipes gathered from a rusty bucket in Chaulk’s storeroom, each framed with the individual dignity of a portrait. As plentiful on the ocean floor as cigarette butts in a city gutter, these pipes are intimate remains of people long gone – a piece of smoke and breath that tumbled below the waves hundreds of years ago, only to be brought back up again.

Myhr also counts scientists among his collaborators, including Dr. Jane Kirk and Amber Gleason from the Canada Centre for Inland Waters in Burlington. Ab-solutes captures their test samples from the Athabasca River, a waterway that flows through protected parks and oilsands alike before emptying into the Arctic Ocean. Dark petroleum sediments are framed by a downward view into a sample pack that also recalls the contours of the camera’s lens.

Photo: Chris Myhr

This work lends visibility to the sometimes-obscure work of environmental scientists, with whom he continues to collaborate on research into mercury contamination in the Canadian North. As the son of a geologist, Myhr has long learned to reject the opposition of science and art that was so prevalent in his art school days. Both artists and scientists, he has observed, share a common interest in discovering new perspectives on our world. “I’ve realized that they’re really creative people doing very important work.”

Born in Calgary and widely travelled since, Myhr has proudly made his home in Hamilton’s North End since joining the faculty at McMaster University in 2014. His attraction to this place is closely tied to its waterways, which he often explores by foot, bike and kayak. He first noticed a thick green sludge floating on the water during a paddle some eight or nine years ago. He shared his snapshots with colleagues at McMaster, one of whom pointed him to reports of the blue-green algae bloom afflicting the harbour.

As with much of Myhr’s work, this first-hand encounter was a starting point for deeper research into cause and effect. With advice from colleagues at McMaster, Myhr evaporated droplets of the contaminated water onto small, thin sheets of glass. These slides, precariously stacked on a digital film scanner, resulted in his Suspensions series – large ghostly photographs of bacteria drawn from our local lake. These images reveal suspended fragments of microbial life in fluid traces that come close to breaching their circular frames, highlighting the uncontrollable quality of his subject.

Myhr has long observed an uneven patchwork of stewardship and abuse surrounding the Great Lakes. While communities like Toledo have fought to enshrine the rights of water in law, Lake Erie is also home to heavy industry, fracking and dumping. A walk with a friend along the western shoreline of Point Pelee introduced Myhr to dark, rubbery chunks of hydrocarbon sediment washing up from Lake Erie’s various industries. Samples of this deathly black substance are displayed in the exhibition and enlarged in photographs that nearly obscure each individual rock against its own darkness. More recently, after Salients opened, Myhr found similar fragments on the pier near the Skyway Bridge, washed up from Lake Ontario by a recent storm.

His love of Hamilton’s waterways remains deeply troubled by the reality of a municipal bureaucracy that has allowed sewage to be dumped into the lake, even with full knowledge of the consequences. “Someone had to sign off on that – someone that does not have a direct connection with the city, the land, the water, the people.” He recalls the many people who flocked to the waterfront during the darkest days of the pandemic to boost their physical and mental well-being – people who, in turn, found their own emotional connection to the water and have learned to care for its survival.

Myhr’s singular lens insists that we look closely to our water and understand how its health and ours are intertwined. Without that connection, disaster soon follows.