Artist Ravinder Ruprai is taking on trauma

She explores her own cancer diagnosis, loss of loved ones, racism, pain, and global migration through her fibre and fabric art works.

I visited Ravinder Ruprai’s short-term studio nestled in an idyllic Strathcona garden where two massive box frames awaited their transformation. One loomed over us on its easel, while the other lay flat like a patient awaiting surgery. The solid wood gold-leafed frames are dramatically scaled up from the more intimate Gold Box works she began at the peak of the pandemic, and are almost impossibly heavy with an overwhelming physicality that Ruprai clearly relishes.

“We can only do so many absurd things as artists, right?”

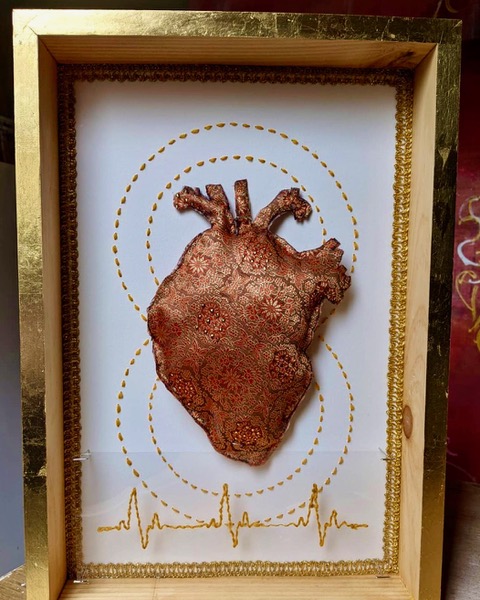

Within these frames, Ruprai is nestling soft sculptures that could imply the comfort of a child’s toy, but seethe instead with the suggestion of swollen bodies, of secret organs exposed to reveal the under-acknowledged pains and ailments that female bodies are often made to bear. A heart made from the exquisitely embroidered blue cloth of her mother’s clothing is scaled to fit a box nested within one of the two large frames – the first piece of a puzzle underway during our conversation, and one that resonates with memories of family members lost to heart conditions.

Her parents, Sikhs from the Punjab region who moved to England along with their first child in the early 1960s, gave birth to six of their seven children in Birmingham including Ravinder before moving to Canada in 1975. Her family established a textile factory in Cambridge that was the backdrop to her childhood and would influence Ruprai’s recurring use of fibre and fabric in her work.

An economic downturn in Cambridge sent the family to Brantford where Ruprai credits her excellent high school art teachers for supporting her application to McMaster’s studio art program, where she immediately fell in love with the small scale of its studio community. She moved to Hamilton at the end of her third year, and has remained here ever since.

Ruprai graduated from McMaster in 1993 and, alongside her musician boyfriend and eventual husband and technical assistant Jamie Oakes, lived “a real rock and roll lifestyle” in Hamilton’s art scene. Her depth of community involvement led to a job at the Art Gallery of Hamilton that combined exhibitions coordination and public programs before her position was abruptly made redundant during a major restructuring in 1999.

The downsizing was deeply demoralizing. Finding a lack of reassurance among her peers, Ruprai quietly withdrew from the art scene; the difficulties of exhibiting at the Toronto Outdoor Art Fair while pregnant further convinced her that art’s demands were incompatible with her own well-being. Ideas and inspirations remained quietly tucked away while Ruprai gave birth to two more children and focused on her young family instead.

The shockwave of a cancer diagnosis in 2012 as well as the tragic news of her former professor and friend Graham Todd’s death from cancer in 2013 pushed Ruprai back towards art with renewed determination.

“I don’t want to run out of time this time.” While her cancer and family history contribute much to her growing body of work, Ruprai’s explorations of migration and trauma are global in nature; one work in her temporary studio features a meandering red line that mimics the Radcliffe Line of Partition, a dark period lived by Ruprai’s parents yet seldom mentioned in her family. She evokes the trauma of the earth as much as the individual body, tracing genocides and their scars with subtle sensitivity.

She began her Gold Box series of mixed media works in 2021 while undergoing trauma counselling. With three children in remote schooling during the peak of the pandemic, it was a risky and vulnerable time to unpack the aftershocks of her cancer experience – “scary as shit,” as she puts it – with a blunt edge that Graham Todd would have appreciated.

The contents of these box frames contain the traces of what transpired in her body during her stomach cancer, and forge the links between mind, body and spirit that emerge through disease and healing. In her hands, the textiles of her childhood become skin and organs for the body and its betrayals of self, with needlework as a means of suturing wounds. The box itself carries its own symbolic weight – think Pandora – while recalling a scientific habit of compartmentalizing knowledge into parts to be studied like butterflies pinned for display.

Braiding is used to tie together the three-fold forces of past, present and future while speaking to the sacred status of hair in Sikh culture and many others in which women have shared wisdom while braiding each other’s hair. Entangled here, too, is the racism faced by her male relatives who were compelled to remove their turbans and cut their hair to gain employment in Canada, as well as Ravinder’s own hair loss during her cancer treatment.

Everything within Ruprai’s creative language is similarly weighted with meaning. The rug hooking that serves as a backdrop for some of her Gold Box works is a traditional craft that evokes something of mindless factory labour yet opens a pathway to meditative transcendence in the making. In her lavish use of gold leaf, Ruprai enthusiastically embraces a self-professed Indian love of gold while drawing from western art history in which gold embellished portraits of saints and summoned the Holy Spirit to earth.

Underscoring it all is a search for transformation, and recognition of the self that can surpass its trauma. As Ravinder’s journey has shown, a shining future can always be found after pain and loss.