Restless creation

Shelley Niro produces art through painting, photography, beadwork and filmmaking and her retrospective exhibition ‘500 Year Itch’ at the Art Gallery of Hamilton pays homage to her prolific work and its hope for the future.

Huddled in a coffee shop on the first properly cold day of winter, Shelley Niro and I thumb through the glitter-encrusted catalogue of her retrospective exhibition “500 Year Itch.” She is looking for Cherry Picker, a painting of a young 1960s-era woman gathering cherries in the looming presence of an astronaut. In the cosmos beyond them both, small white shapes fly on tails of fire.

“Are those spaceships?” I ask, squinting closer. Shelley’s grin is kind yet mischievous.

“No, burning bras.”

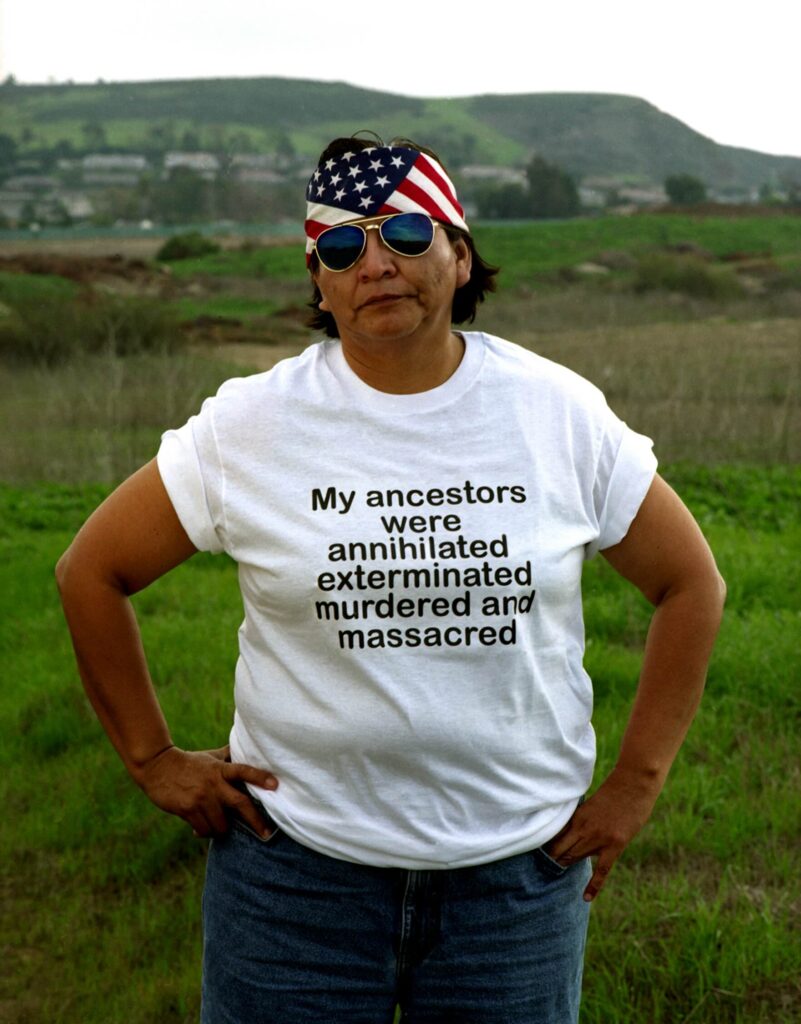

This is characteristic of Shelley Niro’s art – the dreamlike visions that soar on the heels of a lived-in feminism, the political stakes that tug one firmly back to Mother Earth. Her humour gentles the harsh realities exposed in sharp-tongued works like The Shirt – a photographic calling-out of land theft and genocide spelled out on a series of T-shirts that lands on the punchline of “And all’s I get is this shirt” – before the shirt, too, is snatched away. Niro recalls being driven away from her first location choice by a California park ranger threatening fines for using her large-format camera rather than a “family camera,” adding a ridiculous layer of irony to this now-iconic work by one of Canada’s most prolific artists.

Following its debut last year at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in New York City, “500 Year Itch” is now on view at the Art Gallery of Hamilton before embarking on a national tour. Occupying the vast majority of the AGH’s first floor, this is the largest exhibition in the gallery’s history, and an intimate tribute to the Mohawk artist whose decades of practice are deeply interwoven into Hamilton’s cultural fabric.

Photo: National Gallery of Canada

Tobi Bruce and Melissa Bennett of the AGH pitched the idea of a retrospective to Shelley Niro in 2017, the same year that she won both the Scotiabank Photography Award and the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts. They soon welcomed Greg Hill, then-curator at the National Gallery of Canada, and David W. Penney of the Smithsonian to contribute their respective knowledge of Niro’s work to a curatorial endeavour that has been years in the making.

Even with three curators and an unprecedented commitment of space, Bennett acknowledges the difficulty of paring down Niro’s vast body of work while honouring the many diverse forms in which she creates, from painting and photography to beadwork and filmmaking. The process of revisiting all her creative accomplishments, many of which remain in the artist’s studio and are deeply autobiographical, was an emotionally vulnerable experience for Niro as well.

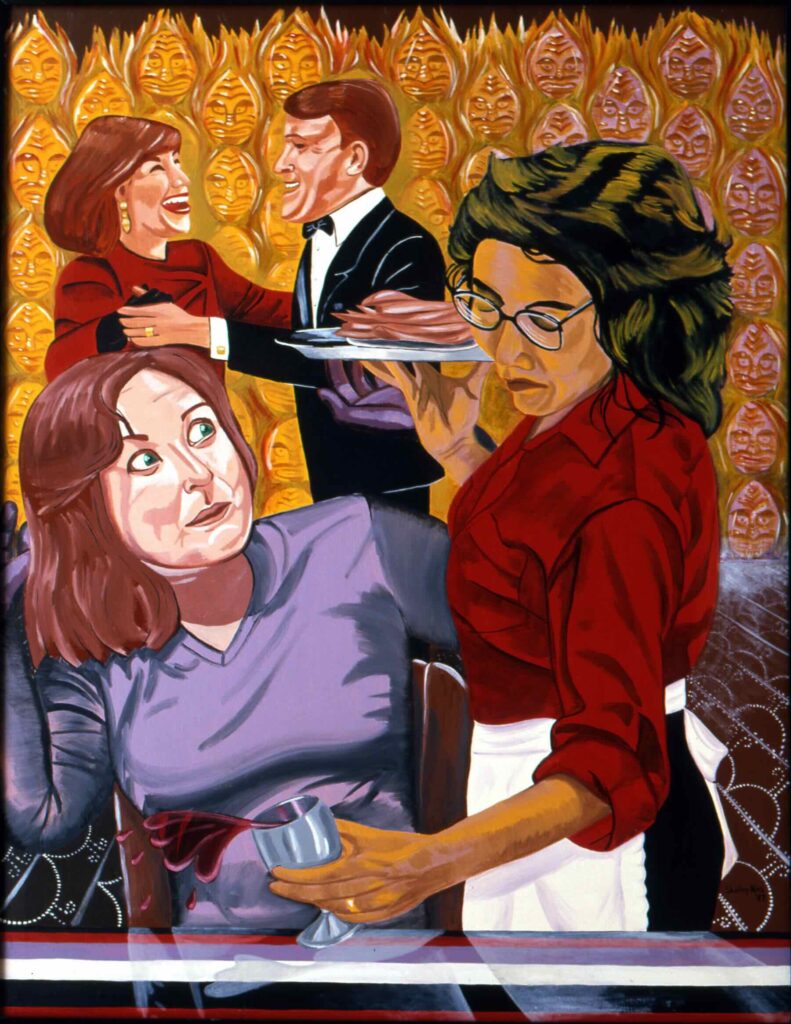

When asked which works were essential to this retrospective, Niro cites Mohawks in Beehives, a series of hand-coloured gelatin silver prints created in the wake of the Kanehsatà:ke Resistance at Oka that depict the artist’s sisters dressed up for a girl’s day out that defies the heaviness of the world, gazing into Niro’s lens with confrontational beauty. This was a foundational first step towards Niro’s many performances for the camera that continue in This Land is Mime Land, a series that strings together sepia-toned childhood photos with performances of popular figures from Santa Claus and Marilyn Monroe to the gold uniform of a Star Trek character. While the women of her family, herself included, are recurring subjects in her work, men appear far less often and, as Niro acknowledges with a cheeky smile, are frequently shirtless. She found it “more interesting and necessary to show depictions of women” to re-assert the matriarchal traditions of her forebears, long overwritten by colonization.

Beadwork is another custom with deep roots in Niro’s childhood, when the craft was widely practised in her family as a means of earning a living. While complicated by the memory of those tourist trinkets, Niro employs beadwork and its patterns with loving patience to elevate her photography and objects with a beauty rooted in Iroquois design traditions that are always evolving. Every ancestral design, Niro notes, was a work of contemporary art at its inception; this awareness has encouraged her to innovate freely upon these traditions.

Niro’s photography has also tested the limits of the medium from the darkroom processes she learned as a student to the onset of digital photography. When photo chemistry became scarce at the turn of the millennium, Niro pivoted to digital methods that she continues to refine with each technological shift in the medium. Her most recent experiments have attempted to capture the moon and stars of the night sky with a powerful telephoto lens. Pandemic Moon is the most successful of these experiments to date, a lightbox-mounted photograph that welcomes visitors to this retrospective and gestures at the forward momentum of Niro’s restless creation.

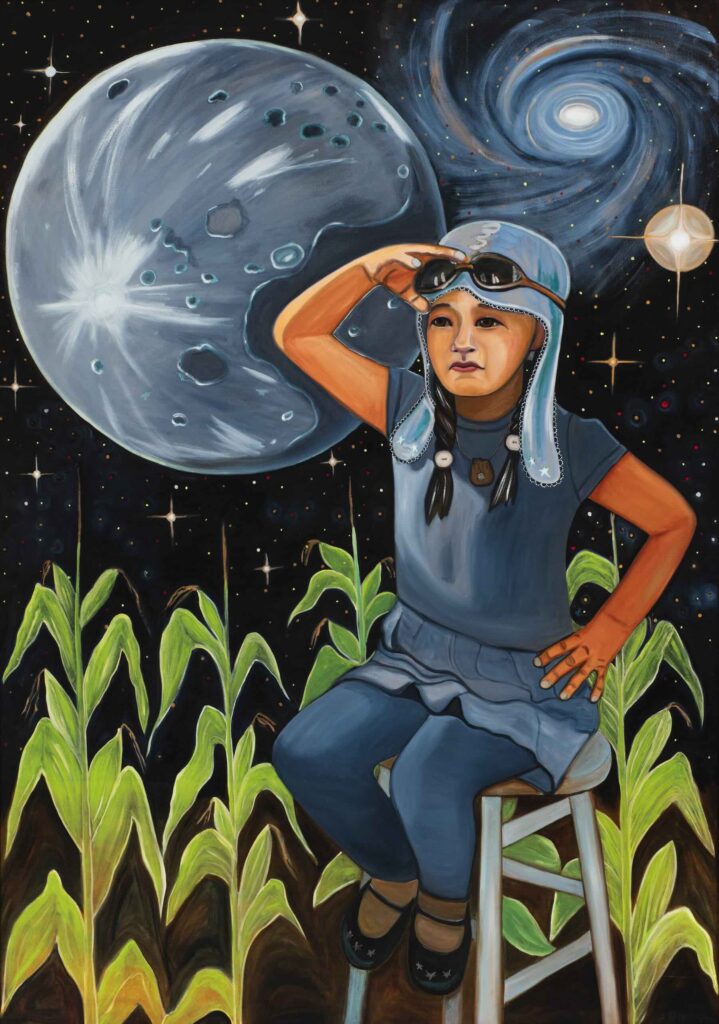

While the past is an ever-present companion, the future burns bright in Niro’s practice. Recent paintings like Black Whole reflect the artist’s anxieties around the fate of satellites and other “space junk” that has been shot into orbit with no plan for its safe retrieval. Raven’s World is a more optimistic portrait of Niro’s granddaughter among the corn stalks of her ancestors, peering into her future from beneath the aviator’s cap that Niro has adopted as a symbol for Sky Woman’s flight from her celestial origins towards the creation of Turtle Island.

In a landmark retrospective layered with knowledge of all that has come before, this exhibition, which runs until May 26, radiates defiant joy and hope for her youngest descendent and all who will walk alongside her into tomorrow.

Art Gallery of Hamilton. Gift of the Women’s Art Association of Hamilton, 2018 Photo: Joseph Hartman

Pandemic Moon (Post-Industrial / Pre-Colonized) 2023. Duratrans in circular lightbox. Edition of six. Co-published with Barr Gilmore, The MORE (or less) Farm, Algonquin Highlands, Ont.

Shelley Niro, The Rebel, 1987/reprinted 2022, hand tinted gelatin silver print Collection of the Artist.