Shining a light

At 62, Hamilton’s Tom Wilson is perhaps more in demand than ever before. Whether it’s books, films, music or painting, he’s determined to use his art to highlight Mohawk culture and combat the effects of colonialism.

UPDATE: 2024 has been a year of honours and new music for musician, author and painter Tom Wilson, who has also embraced his Mohawk name Tehoháhake. Here’s a rundown:

Shortlisted for Playwrights Guild of Canada’s Tom Hendry Awards

Wilson and collaborator Shaun Smyth have been shortlisted for the Playwrights Guild of Canada’s Tom Hendry Awards in the category of Outstanding Musical That Had Not Yet Had a Premiere Production for their work on Beautiful Scars. The awards ceremony will take place on Oct. 28 at the Elgin Winter Garden Theatre in Toronto.

Honorary doctorate from McMaster University

Wilson will receive an honorary Doctor of Laws from McMaster University in recognition of his contributions to the arts and his work advocating for Indigenous communities. The ceremony is Nov. 20 at FirstOntario Concert Hall in Hamilton.

Lifetime Achievement Award in Music – International Peace Festival

Wilson was honoured with the Lifetime Achievement Award in Music at the International Peace Festival on Sept. 28 at the King Edward Hotel in Toronto. This prestigious award highlights his career-long commitment to creating music that transcends boundaries and advocates for peace.

New Music Release – “Death Row Love Affair” (recital version)

Wilson has released a new version of his song “Death Row Love Affair,” an alternative take that serves as a preview of a forthcoming album. The song, which was a powerful closer in the stage musical Beautiful Scars, has been reimagined as a haunting, introspective track produced by Gary Furniss, with contributions from Thompson Wilson, Jesse O’Brien, and Aaron Goldstein.

Upcoming performances

Wilson will perform with Junkhouse at multiple venues across Ontario this fall, including Ottawa, Peterborough and Brockville, along with two nights at the legendary Horseshoe Tavern, Toronto, Dec. 6 & 7.

Art exhibitions

Wilson’s artwork will be showcased in two upcoming exhibitions:

RESPECT III – Group Indigenous exhibition at Beckett Fine Art, Hamilton, Sept. 28 to Oct. 19

Mohawk Warriors Hunters and Chiefs: The Art of Tom Wilson – solo exhibition at TAP Gallery, London, Ont., Nov. 14 to Dec. 16. On Dec. 3, TAP Gallery will also host a screening of the Beautiful Scars documentary, followed by a discussion with director Shane Belcourt and Wilson.

Putting his first memoir out into the world was a terrifying moment for Tom Wilson. So, of course, he’s writing another one.

Hamilton’s troubadour has been writing songs and performing since he was a teen lugging a guitar to coffee shops and pizza joints in downtown Hamilton.

But that’s a far cry from baring his soul in Beautiful Scars: Steeltown Secrets, Mohawk Skywalkers and the Road Home, the 2017 bestseller that told Wilson’s story of growing up in an insular home of hidden truths, his battle to overcome addiction and his journey to discovering his identity.

A documentary of the same name debuted at the Hot Docs festival in Toronto in May. Wilson says it took him four days to watch it after filmmaker Shane Belcourt sent it to him in advance of the premiere.

“It’s just so weird. It’s like showing your ass in public in a way. The camera is like a confessional. When you’re talking, you forget it’s being recorded.”

Wilson learned through a happenstance meeting with a stranger at the age of 53 – and after the death of both his parents – that he was adopted.

Rather than being the son of Irish-Canadian blind war veteran George Wilson and French-Canadian homemaker Bunny who made a home with him on Hamilton’s east Mountain, he was the son of Janie Lazare, a woman he believed to be his first cousin. He was also 75 per cent Mohawk.

Wilson always suspected his family didn’t add up, but was hushed any time he asked.

The intimate film, just like the book it comes from, is at turns shocking, funny, poignant and gritty. Featuring a soundtrack composed by Wilson and his son Thompson, the documentary is the perfect complement to Wilson’s memoir. The latter is told only in his voice, while the former hears from those deeply affected by Wilson’s story – namely his birth mother, his daughter and his half-sisters.

Viewers can’t help but be captured by Lazare’s strength and vulnerability and the understated way in which she talks about being allowed to be only on the periphery of her son’s life. Though Lazare was often present as Wilson grew up, Bunny did not allow her time alone with him.

Lazare, who is 82 and lives in Dundas, initially didn’t want to be in the documentary but Belcourt, an award-winning writer and director of Métis descent, convinced her to take part.

Lazare, a tiny, wise, white-haired woman, was told as a child in residential day school in Quebec that she was the “last of the Indians,” says Wilson.

“She is a survivor. And I’m a survivor and my kids are survivors,” says Wilson. “She’s really the star of the film, along with my daughter Madeleine. Janie was nervous about doing it and she was nervous about seeing it on the screen. But she shines in it.”

Wilson is now in the thick of writing his second book called Blood Memory, which contemplates ancestral and genetic connections to one’s culture and identity. It’s scheduled to come out next fall.

“There are things that resonate with us and we don’t know why. They are already part of us, already inside of us. That’s what this book explores.”

There is a lot to live up to after Beautiful Scars, a national bestseller that received glowing critical reviews and was named a finalist for the 2018 Kobo Emerging Writer Prize, a finalist for the Hamilton Literary Awards, and was named a CBC Best Book of 2017.

When Wilson met renowned book editor Martha Kanya-Forstner to discuss his first book, he thought someone else would do the writing after he spilled his tale.

“She was both amused and insulted. She told me I had to go through the physical process of writing it myself. She was right. I had to go through that painful, hard work.”

He half-jokes that writing the book saved him hundreds of thousands of dollars on therapy.

“The first time I sat down to write, I wrote with such a black heart and anger about being lied to my entire life. But when I started to write about Bunny and George, I felt as if I was three years old again. They were the centre of my world. I once couldn’t imagine the universe without them. That black edge started to break up.”

After crossing that bridge, his goal now is to “bring honour and shine the light on Mohawk culture and the effects of colonialization on Indigenous communities. I’m telling my story for that reason.”

The writing of Blood Memory comes in fits and starts. There are stretches where he is fully immersed in the book, but then either creative pulls or looming deadlines lure him back into painting, song writing or recording.

His favourite creation is the one rolling around in his head.

“There is excitement in the unknown. Artists are explorers and risk-takers. Artists have told us what the moon was like or what was on the ocean floor long before any explorer or scientist got there.”

From his solo work in Lee Harvey Osmond to his painting, Wilson continues to grieve for the absence of his Mohawk identity in the first half-century of his life.

His installation called Fading Memories of Home, featured at the Stratford Festival this summer, hauntingly symbolizes the loss of family, culture and identity that Indigenous children suffered at the hands of governments and churches. As viewers move past nine rebuilt residential school desks, projected images of families disappear.

Wilson’s art was also featured in an 18-piece exhibition entitled Echoes Of The Flame: Art Inspired By The Lyrics Of The Tragically Hip.

Wilson’s eight-foot piece is that of a shrouded, blood-spattered nun whose robes are inscribed with the names of more than 1,000 children found buried at Canada’s residential schools.

The lyrics from The Hip’s scathing “Now The Struggle Has A Name”, a protest song about Canada’s treatment of Indigenous people and the generational pain it has created, are also included in the painting: “It doesn't fade, it hasn't changed/ I still feel the same/ Now the struggle has a name.”

It’s telling that for all the drugs and bar fights of his rock ‘n’ roll life, Wilson’s first and only arrest came when he visited the disputed McKenzie Meadows housing development site in Caledonia to deliver food to protesters and perform for families in October 2020.

He was charged with mischief and disobeying a court order. He wishes he could have stood alongside his siblings in land battles long before now.

“I want to be part of creating a world that no longer needs the word reconciliation and that doesn’t need to apologize to our grandchildren for what we were. But only love changes the world.”

So in that vein, Wilson established the Tom Wilson Scholarship in Honour of Bunny Wilson at McMaster University in 2020. It will support first-year Indigenous students from anywhere in Ontario in any faculty.

The scholarship is supported by a range of contributors, including a $100,000 donation by McMaster.

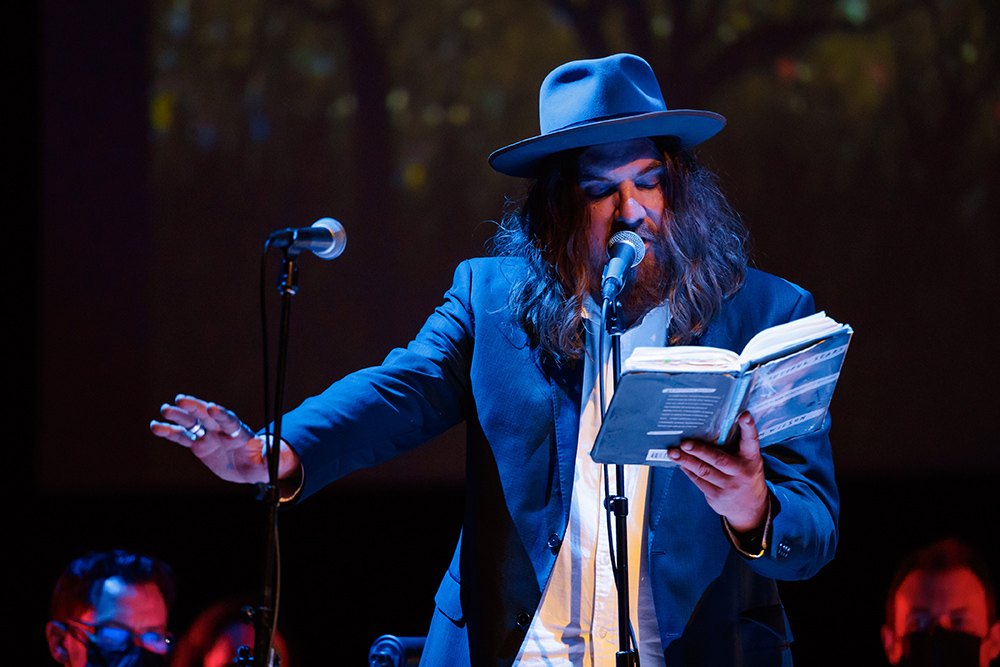

Two fundraising concerts finally performed in May after two years of pandemic postponements included a small orchestra led by Darcy Hepner, Wilson’s son Thompson Wilson, long-time Blackie and the Rodeo Kings bandmate Colin Linden, Indigenous musician Phil Davis, and Hamilton singer-songwriter Terra Lightfoot.

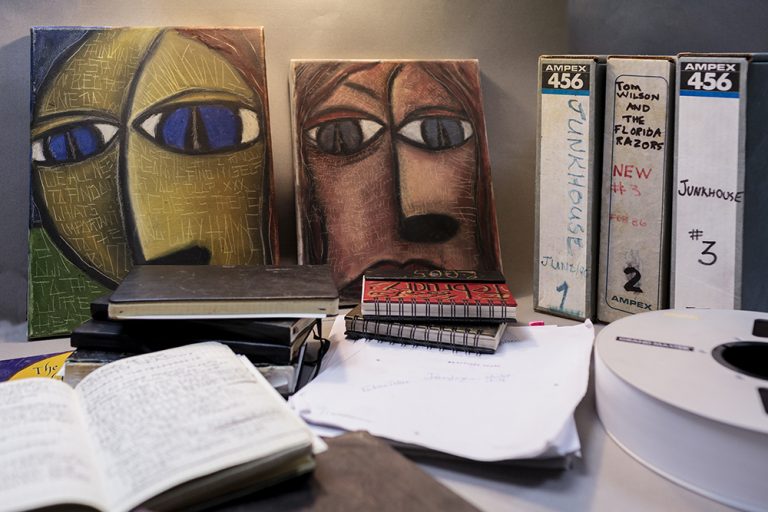

Wilson also recently donated his archives to the McMaster University Library, joining other musical luminaries such as Bruce Cockburn, and Hamiltonians Ian Thomas, Valerie Tyron, Jackie Washington and Boris Brott, and writers Farley Mowat, Margaret Laurence, Pierre Berton and Stuart McLean.

Wilson’s archive contributions include notebooks filled with thoughts, song ideas, and lyrics, vinyl recordings and photographs, notes and annotated galley proofs of his memoir and some paintings.

“I had no chance of ever being accepted here. I wasn’t built for that kind of learning. As a young man, I only had a burning desire to create art,” Wilson said during the dedication of his archives at McMaster in May.

“We are all trying to do the very best we can. But I don’t know what I’m doing. I never have. Ask my manager, ask my family, ask my teachers in high school.”

For someone who doesn’t know what he’s doing, Wilson sure is busy doing it.

In addition to a new album, O Glory, from Blackie and the Rodeo Kings, Wilson’s year has also included an album collaboration with fellow Indigenous singer and former Hamilton resident Iskwē, with songs co-written and produced by Serena Ryder.

Blackie and the Rodeo Kings formed in 1996 for what was supposed to be a one-off tribute album to the music of Canadian great Willie P. Bennett. It has grown into a genre-blending supertrio that includes Colin Linden and Stephen Fearing, blending southern-style rock, blues, country, Americana and folk.

Things were clicking in early 2020 – the band’s 25th anniversary – with the release of King of This Town, a new major label deal with Warner Music Canada, and a tour that included debuts at the venerable Grand Ole Opry and Bluebird Café in Nashville.

Of course, it all ground to a halt in March of that year. And Wilson readily admits he happily found a routine that included staying close to home.

On a beautiful June morning at his Kirkendale home, Wilson says he’s not looking forward to the long tour for O Glory running from July through December (including a stop on Dec. 10 at Hamilton’s FirstOntario Concert Hall.)

As a 62-year-old grandfather of three who’s perhaps more in demand than ever before, who can blame him?

The pandemic offered him a chance at a new perspective, says Wilson.

“I do feel exhausted. By 8 p.m., I’m ready to put my feet up. But I know adrenaline will kick in on the stage.”

“All the business bullshit went away and I got to do what I want, which is create. I wrote songs for Black and Rodeo Kings. I came to the studio and painted.”

There were no airports. No waking up in hotel rooms.

“That life might sound glamorous but after all these years, I could not do that again and be OK with it,” he says.

“I’ve been on the stage my whole life now. I didn’t think this was the break I needed, but it was. There is no retirement in this business but I found out that I wasn’t at a loss without performing when I had to give it up.”

Wilson has been married to his second wife Margo for seven years and his daughter Madeline, her partner Ryan McMillan and their three youngsters live just two blocks away from Wilson’s English cottage-style house on a beautiful street off Queen Street just before it climbs up the escarpment.

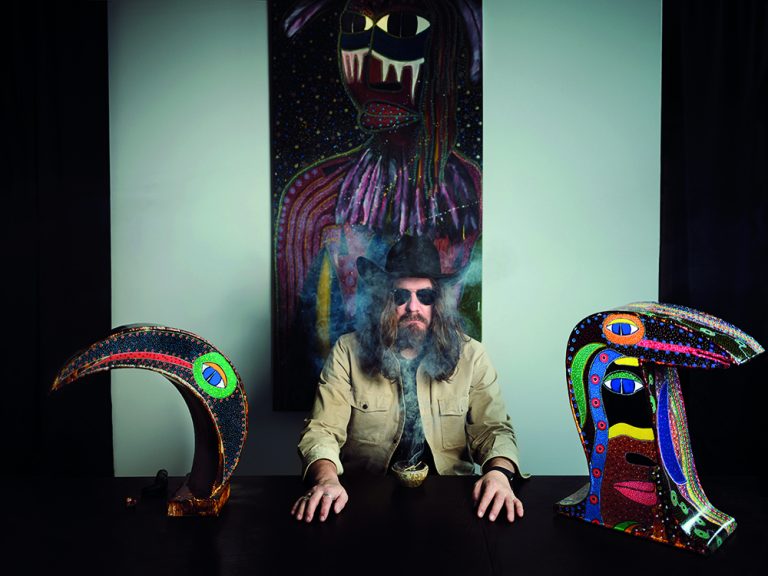

He is tall, with a booming baritone, intense eyes and strong features that would make a wood carver eager to get started on his likeness. His signature style – long hair and beard, boots and hat would look far too intentionally “authentic” on most anyone else.

Though he looks badass, no one can be intimidating who is out shepherding his grandsons to school or taking his mom for groceries.

But throughout Beautiful Scars are glimpses of the hard edges of the Hamilton Wilson grew up in – a violent, gritty, survival-of-the-fittest type place where kids weren’t protected or coddled. They were toughened up for a cold, cruel world.

Wilson’s clean, bare bones style of writing stares you right in the eye. He refuses to depict himself as a hero or even with much sympathy. His accomplishments he diminishes and his weaknesses he flaunts. He writes unflinchingly about the heartbreaking end of his first marriage and the loneliness of his stint in rehab.

He watches RuPaul’s Drag Race a lot these days (he says his wife likes it.) At the end of each episode they show a picture of the drag queen contestant at eight or nine.

“They ask them what they would say to that kid and it’s so moving and emotional because it’s such a universal feeling to look back and wish you could tell yourself something. I was a devil,” he says.

“There is regret you live with. You can’t shake it. You might change and clean up and live a better life but the people you f*cked up are still f*cked up and you can’t shake that. I’ve hurt people and I have to live with that.”

Whenever he can, he finds time to be in his studio space at the Cotton Factory on Sherman Avenue North. On this day, he’s adding “10,000 dots into the sky” of a large canvas that takes up most of a wall. It’s unlikely he’s actually calculated that number, but it doesn’t seem an exaggeration given his highly detailed, mesmerizing work.

As Wilson toils, Lucy, his spunky, sweet border collie/Australian shepherd/German shepherd mix is never far from his side.

Wilson started painting when he quit drinking in the early 1990s. It was an outlet, a way to fill his time and to be productive. He started out giving them away.

But that’s certainly not the case anymore when a Tom Wilson painting captures tens of thousands.

But the outlet is the same.

“There is a mindfulness to it. I can lose myself for hours in it. It centres me.”

Wilson says it might be easy to think an artist spends a lot of time in contemplation, searching for inspiration.

“That’s not it. It’s hard work. It’s discipline. Sometimes you come up empty… I had to learn that when I got caught up in trying to control the reception or trying to write the hit or writing for an audience you hope exists, it’s trouble.”

Humans are born to create, he says. Kids sing and drum and dance and make up stories but many lose that instinct as they grow up.

“I never say I’m an artist. I’m working every day to become one. And when you’re working as an artist, you are really trying to be a three-year-old version of yourself.”