The Flip Side of Urban Sprawl

Preserving Hamilton’s rural character needs to be a high priority for economic and environmental reasons.

When we usually talk about city development and sustainability, too often we focus on the urban part of our city. We discuss how neighbourhoods are developing, where housing is being built, opportunities for intensification, downtown renewal, or the implementation of rapid transit, for instance.

However, this is an incomplete discussion. What about the rural part, where suburban housing ends and farming fields begin?

The very nature of urban sprawl looks awkward on the landscape because it typically abuts a rural landscape that couldn’t be more different. So when we talk about the city’s future, we should ask, what will be the impact of development on the rural character of the community? This is particularly important considering the urban boundary debate that sought to expand city development into rural land. While city council, backed by residents, called for a firm urban boundary, the Province of Ontario tried to force a massive expansion on Hamilton, before backtracking under intense public pressure.

So, what is at stake when we consider expanding the urban area at the expense of our rural landscape?

To begin with, we need to understand the nature of the area we are talking about. In Hamilton, this isn’t a small area, as rural land makes up the vast majority of land mass within city boundaries. According to City data, about 80 per cent of Hamilton’s land mass, close to 220,000 acres, is rural.

Within this massive area, communities are less dense than within the urban area, and services are sometimes delivered differently, or as with transit, not at all. Unsurprisingly, a major economic sector of rural Hamilton is agriculture. However, what is less well known, is the impact of this sector on the Hamilton economy.

A billion-dollar sector

A 2022/2023 economic snapshot released by the City of Hamilton paints a data-rich picture of this sector. Overall, agriculture is a billion-dollar sector, with a gross output impact of about $1.3 billion. This involves:

- A direct impact of about $240 million, which includes business activity occurring as the result of direct sales of goods from Hamilton's farm sector.

- An indirect impact of about $650 million, which includes business activity from farms to other businesses, including services at the retail, wholesale, and production level.

- An induced impact of about $445 million, which includes business activity that results in spending on food, clothing, shelter, and other consumer goods and services as a result of the workforce at the businesses that create the direct and indirect impact.

Agriculture represents thousands of acres and jobs

In terms of land mass, there are 118,070 acres of farmland within City boundaries. This represents approximately 13.2 per cent of the Golden Horseshoe's total farm area. In 2021, Hamiton had 679 farms with an average farm size of 174 acres and the farms (on average) were the most profitable in the Greater Golden Horseshoe. In terms of jobs, it is estimated that agriculture employs 2,207 people including full-time, part-time, and seasonal workers.

Where do farms do their business? The vast majority, 79 per cent, don’t sell directly to consumers. Of the 21 per cent that do sell directly, this includes 112 farms selling from their farm (e.g. at stands or pick-your-own), 45 delivering to consumers and 27 selling at farmers’ markets.

The quality of Hamilton’s farmland

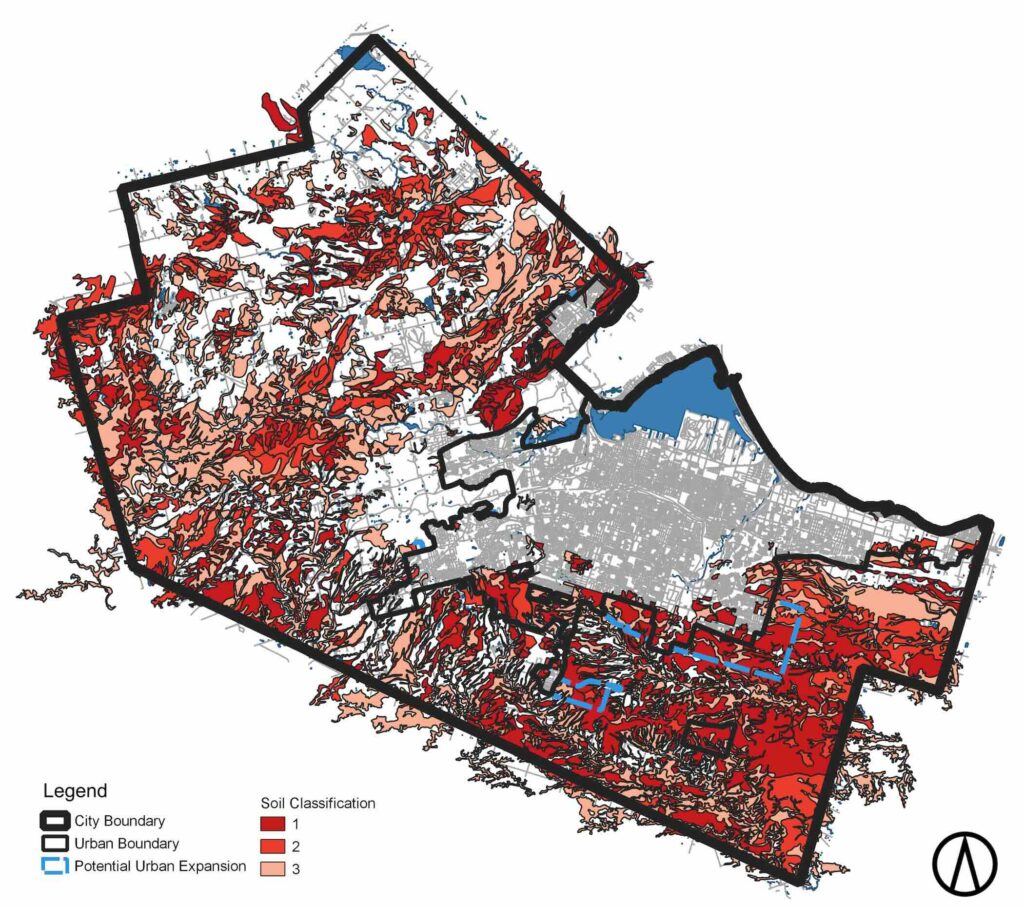

Aside from the economic snapshot, the other part of understanding the agricultural sector is to gain insight into the quality of the farmland itself. To do this, the Canada Land Inventory (CLI) is useful. There are seven classes used to rate agricultural land capability. Class 1 lands have the highest and Class 7 lands the lowest capability to support agricultural land uses. While there are other ways to rank the quality of land, the CLI is used to inform many jurisdictions for land use planning purposes.

It is important to note that prime agricultural lands, Classes 1, 2, and 3, are a very limited resource in Canada. Only 5 per cent of the Canadian land mass is made up of prime land, and only 0.5 per cent of this prime land is Class 1. The Greater Golden Horseshoe contains a significant portion of this very limited resource.

The accompanying map illustrates the quality of farmland in Hamilton. The thick black line is the city boundary, whereas the thin black line is the urban boundary where city development is allowed. The areas in the three shades of red represent Classes 1, 2, and 3 of farmland. What this map shows is that Hamilton has a significant amount of prime agricultural land within its city boundary, especially the south-eastern part of the city.

Agriculture versus urban sprawl

This is particularly important in the context of the current urban boundary debate. Back in 2021, after a large public mobilization, city council voted to freeze the urban boundary and accommodate growth within the current built-up area. In 2022, the province unilaterally decided to override council’s decision (along with other municipalities) and forced an expansion into rural lands. Looking at the map, the areas of forced expansion are indicated by the blue dotted line. It is clear that the proposed areas for urban expansion were at the expense of mainly Class 1 agricultural land, some of the best in Canada.

Fortunately, in 2023, the province reversed its decision on forced expansions, giving Hamilton the opportunity to return to a firm urban boundary and preserve the areas of prime agricultural land. In short, the ball is back in Hamilton’s court. Knowing what we know now about the importance of farmland to food security and environmental sustainability, why would anyone destroy a tier one resource? We can’t manufacture this quality of land and we need to elevate its protection in our planning and economic development.

This is made even more clear as we simply can’t afford the alternative: urban sprawl. Sprawl is expensive. The City of Ottawa actually put a cost on sprawl and revealed that it costs $465 per person each year to serve new low-density homes built on undeveloped land. On the other hand, higher-density infill development pays for itself and leaves the City with an extra $606 per capita each year. It is not unreasonable to assume these numbers are similar for Hamilton.

So on the one hand, we have a billion-dollar economic sector made possible by a local land resource that is only found on 5 per cent of all the land in Canada. On the other hand, we have potential development that eliminates a valuable resource and is a net drain on local coffers.

That’s the choice.

Put another way, why would any city destroy a major economic asset and replace it with something that is unsustainable from both an environmental and economic perspective?

No clear thinking community would make that choice, and neither should Hamilton.

Paul Shaker is a Hamilton-based urban planner and principal with Civicplan.