The Workers Arts & Heritage Centre : A force of labour

The WAHC was founded by working people for working people – a rare entity in the world of museums.

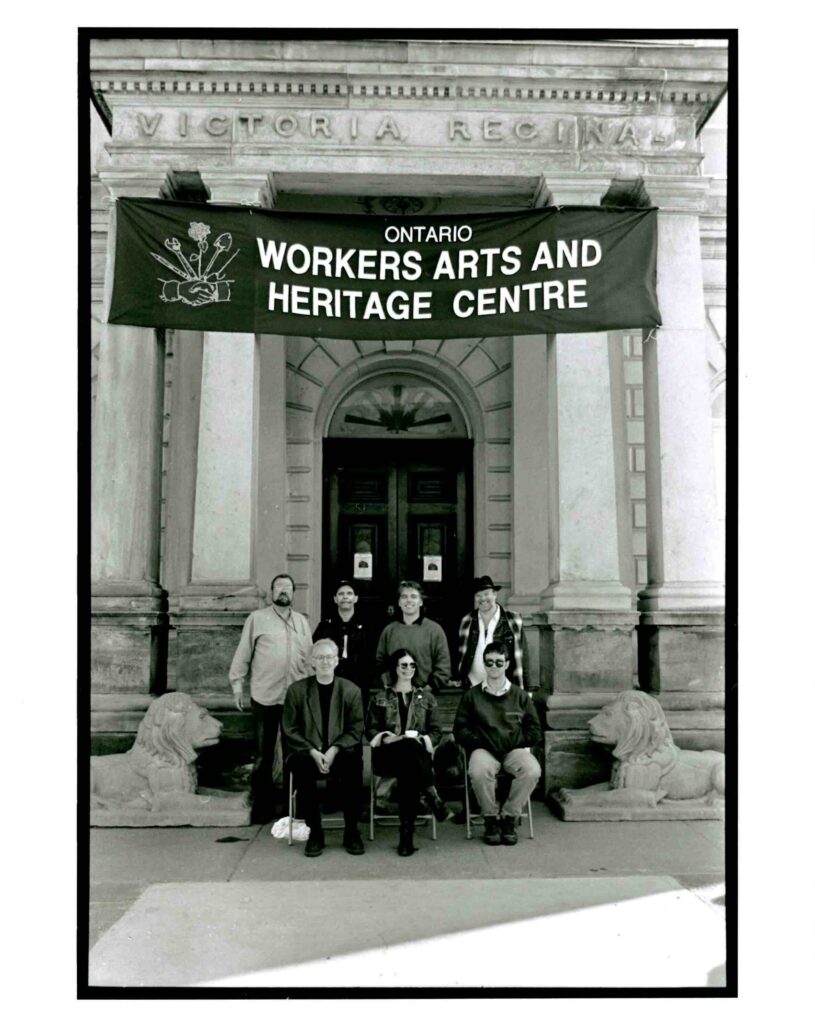

In the 30 years since its founding by a dynamic group of labour historians, artists, and union activists, the Workers Arts & Heritage Centre (WAHC) has transcended its first intentions of being a historical museum.

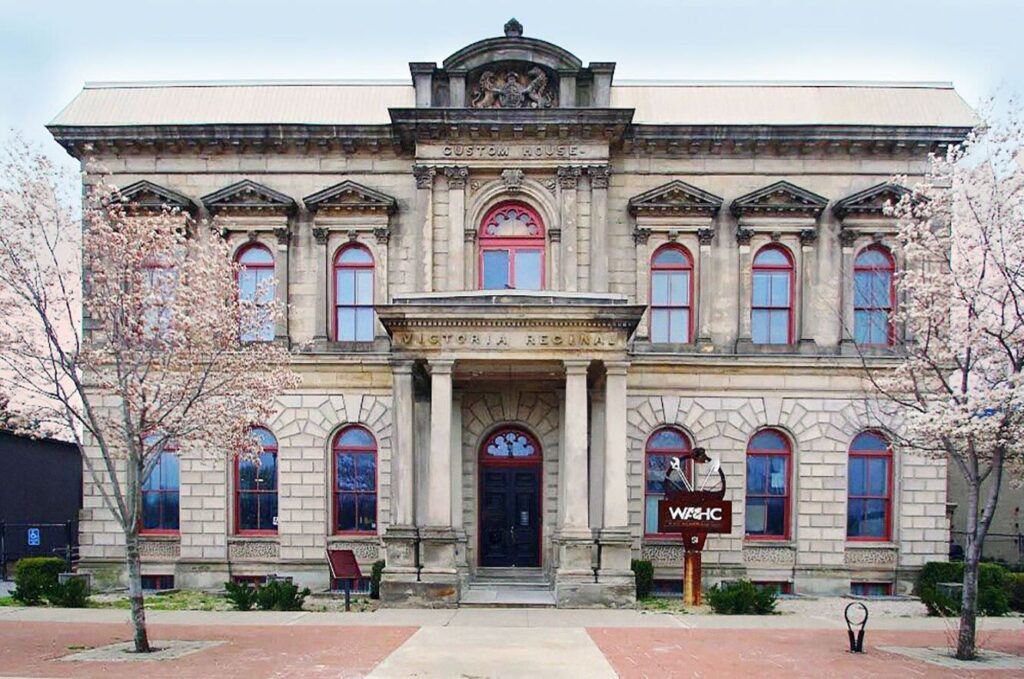

Today, it stands as a vibrant cultural centre activated by people-driven programs. “We’re kind of a hydra-headed beast now,” says executive director Tara Bursey. Beyond its exhibitions, this is a space built by communal gatherings and actions: workshops, performances, songwriting circles, and live wrestling have all found a home within the heritage halls of Hamilton’s former Custom House.

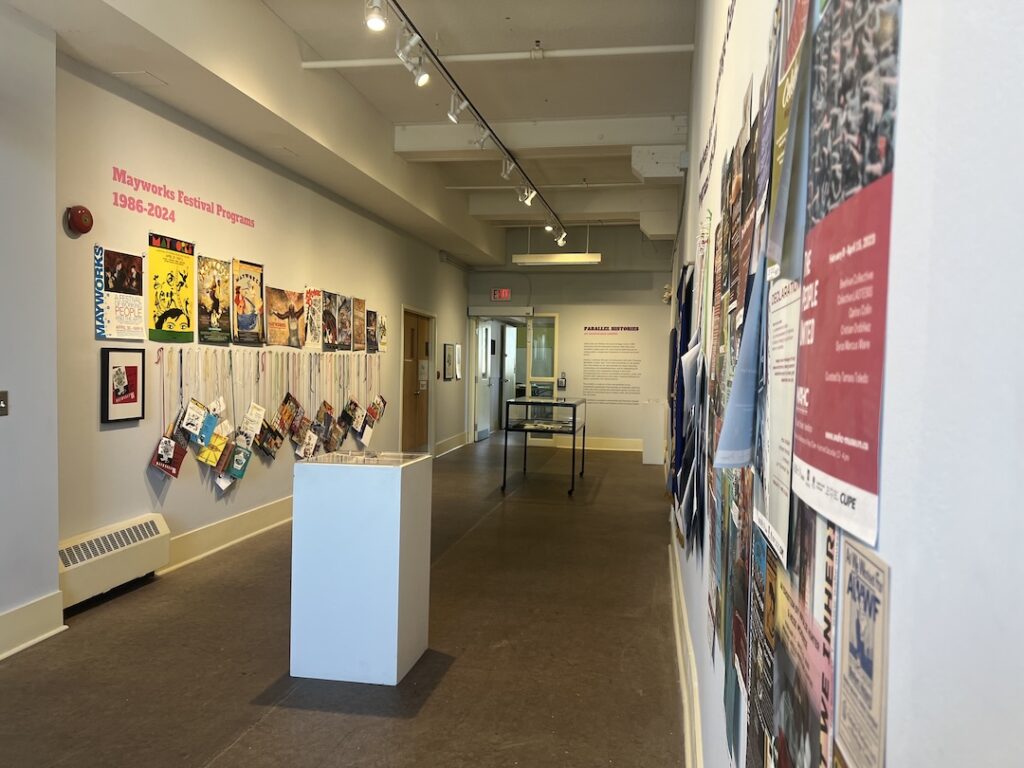

Parallel Histories: An Anniversary Exhibition, curated by previous executive director Florencia Berinstein, is a small yet powerful exhibition in the second-floor Community Gallery that celebrates the anniversaries of both WAHC and Toronto’s Mayworks Festival, a like-minded labour arts organization marking its 40th year. Posters and programs drawn from both institutional archives emphasize a shared legacy of community engaged art-making and an early commitment to centring equity-deserving groups of workers in labour arts. Many pamphlets are dangling on strings in an open invitation to browse their pages: a deliberately unprecious gesture of trust in the community that helped build and sustain this space.

The Workers Arts & Heritage Centre launched on May 7, 1995 as part of a day honouring the anniversary of the Nine-Hour March in 1872 when Hamilton workers marched through the downtown core in a general strike that marked Canada’s first organized demonstration for labour rights. In the poster marking this event and the other materials on view in Parallel Histories, the artist’s hand and voice are ever-present in the work of organizing these movements. Their posters, banners and buttons have built a visual language of protest and solidarity that resonates today.

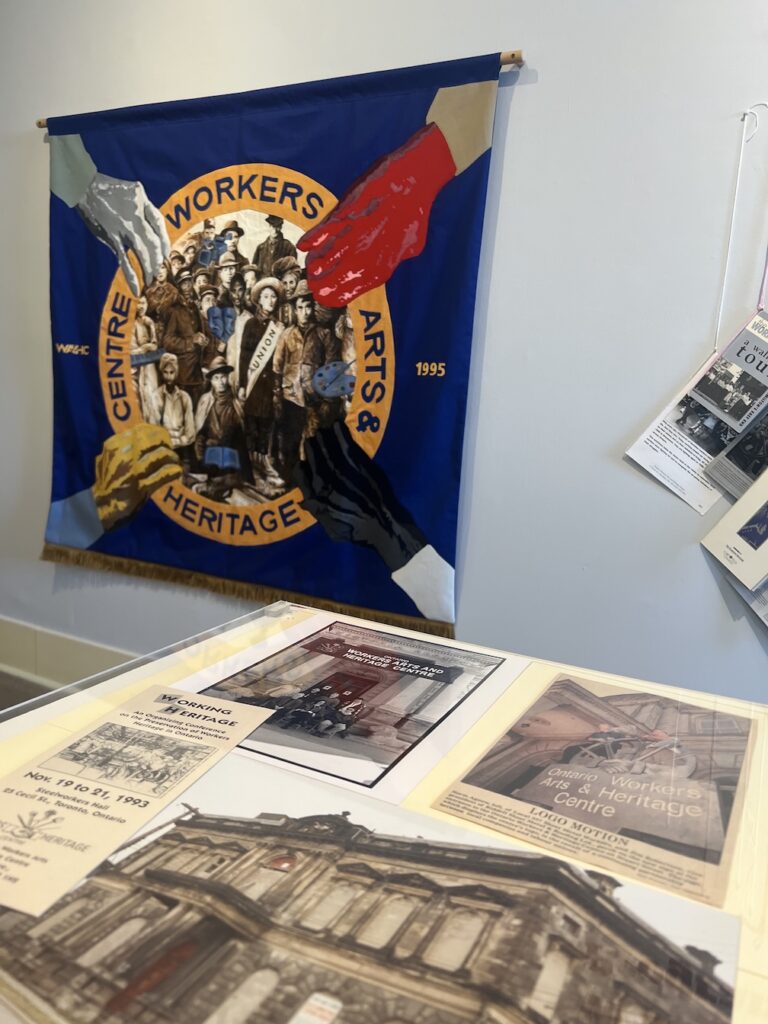

WAHC’s 30th anniversary follows soon after the passing of Carole Condé, a widely respected and influential labour artist who worked most frequently alongside her partner in art and life, WAHC co-founder Karl Beveridge. Her presence is deeply felt throughout WAHC’s history, and is on display in Parallel Histories through a banner she created in the museum’s honour – a lovingly executed creation that combines painting and textiles to depict a diverse group of workers bearing the traditional instruments and tools of the arts.

Bursey was humbled when Beveridge gifted more than 500 objects to WAHC’s collection in Condé’s name. Accessioning this archive of labour arts history was an act of mourning and healing that also foregrounded the intergenerational dialogue that has shaped WAHC’s anniversary program. The collaboration that grew between senior artist Beveridge, Bursey’s mid-career perspective, and the 20-something museum worker hired through Young Canada Works to support the accessioning process was an opportunity to understand the refreshed relevances of these objects, and how the struggles of our elders in the history of work can convey insight and tactics into the hands of a new generation.

WAHC opened its anniversary year with What We Inherit, a two-person exhibition that invited Hamilton artist Natalie Hunter, alongside Heidi McKenzie, to produce new work on her family’s steelworking legacy in Hamilton. This exhibition opened in the early days of trade and tariff disputes with the United States, which continue to cast a dark shadow over our city’s steel industry. In this context, Hunter’s project reveals a circular history of labour threatened by boom-bust cycles that visit their impacts most severely on working people. This resulting artwork also gives a localized, humanizing voice to global strife and its anxieties.

What We Inherit: Steelworker Legacies was a community-sourced complement to this exhibition that invited Hamilton steelworkers to share mementos of their working lives, which were documented following museum standards by members of WAHC’s youth council. Among the expected hard hats and coveralls were objects of great personal value and sentiment, many gifted in recognition for decades of service. To Bursey, these awards convey a tradition of camaraderie once embedded in labour’s rituals – acts of heartfelt respect now largely unknown to the contemporary worker. By engaging youth in the project of documenting these objects, WAHC created space to ask how these traditions have been lost, and whether their return might be possible.

The role of WAHC’s youth council as an incubator for cultural growth cannot be underestimated. The current exhibition, In the Wake of Work: Asian Diasporas, Labour, and Living Memory, was curated by Jojo Chooi-Harley, a former youth council member who has since trained as a social worker and psychotherapist, and now draws upon that professional lens to share the entanglements of family and work within Canada’s Asian communities. By bringing together Holly Chang’s quilted archival photographs, VALU CO-OP’s (Vancouver Artists Labour Union Cooperative) oral histories and an evocative installation and performance by mihyun maria kim, Chooi-Harley reveals the heartbreaking labour of building new lives in an unfamiliar place while honouring ancestral memory.

The Workers Arts & Heritage Centre is a rare entity in the world of museums. Founded by working people for working people, its aesthetics are shaped by the austerity under which it has often operated. This place brings exceptional visibility to the physical and emotional work of preserving the past, in no small part by engaging community as co-authors in the creation of its exhibitions.

Now more than ever, we know that history tends to repeat itself. By sharing the stories of workers’ efforts in the past to create better conditions for the present, this chorus of echoes can provide much needed lessons for creating a just and equitable future.