We must target the ‘ready, fire, aim’ approach

Our municipal officials in Hamilton, and beyond, are prone to hiding behind endless studies and never getting anything done. But it’s time to take action on pressing social issues like homelessness.

One of the highlights of the Democratic National Convention (DNC) in the United States in August was a spellbinding address by former First Lady Michelle Obama, quoting the mother of Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris in her repeated exhortation to “do something” in the face of difficulty.

It’s a message we would do well to embrace in Hamilton, where our municipal leaders have raised not doing something to an art form.

It’s not just Hamilton, of course. Across Canadian cities, as urban advocate Gil Penalosa likes to argue, planners and city leaders are prone to an attitude of “ready, aim, aim, aim…” without ever carrying out a plan.

An urban planner and former parks commissioner for Bogota, Colombia, Penalosa addressed the dearth of public parkland in that city by expanding and popularizing a weekly street closure to transform public rights of way into a city-wide linear park network.

He moved to Canada in 1998 and founded 8-80 Cities, a non-profit promoting the design of public space to be inclusive and accessible.

Sounding a lot like Michelle Obama, he insists that in public policy, “Everything is about focusing on doing” rather than hiding behind endless studies. He says leaders should adopt a “ready, fire, aim” approach in which you launch quickly with a pilot project, get feedback, assess how it’s working, and make adjustments as more information comes in.

Meanwhile, Hamilton councillors got a staff report in August proposing that a City-sanctioned encampment for unhoused residents with security and washroom facilities would cost $112,000 per resident. The response from Mayor Andrea Horwath was … to ask staff to prepare yet another report.

(This reminds me of the time – true story – when the City hired a walkability consultant to help implement policy and the consultant came back with a recommendation to do more consulting.)

Staff also reported that the City is spending $170 million out of its annual budget this year on homelessness supports, of which 70 per cent or $119 million is being covered by the local tax base. We’re spending so much money and yet we’re spinning our wheels when it comes to addressing the root causes of homelessness.

My son recently introduced me to the idea of thinking in terms of “pencil projects” vs “pen projects.” A pencil project is something that easily can be revised or even removed if it turns out to be a bad idea, whereas a pen project is more permanent and needs to be planned more thoroughly.

It seems to me that, while permanent housing for everyone is definitely a “pen project,” our approach to providing temporary and transitional housing for unhoused people would make a lot more sense as a “pencil project” and therefore ideally suited for the “ready, fire, aim” approach in which we – say it with me – “do something” in order to try out ideas and determine what works.

Of course, for that to work we also need to abandon the can’t-do attitude that clobbers every proposal with a litany of reasons it could not possibly work.

For example, when the Hamilton Alliance for Tiny Shelters proposed doing something – specifically, building a pilot project on the grounds of Sir John A. MacDonald school – staff rejected it because the school building is water-damaged and will have to be demolished at some point.

That decision was made in February 2022, and the school building is still standing today. The site could have provided transitional housing – and important data gathering for policymakers – for the past two and a half years. Instead, we did nothing but produce studies.

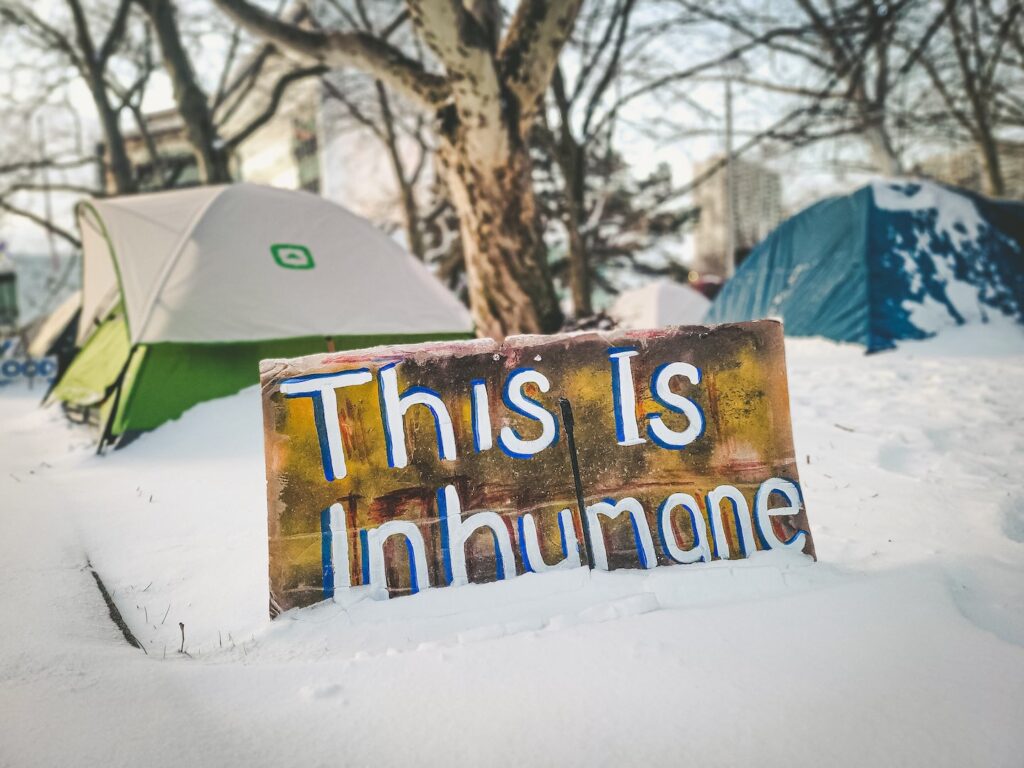

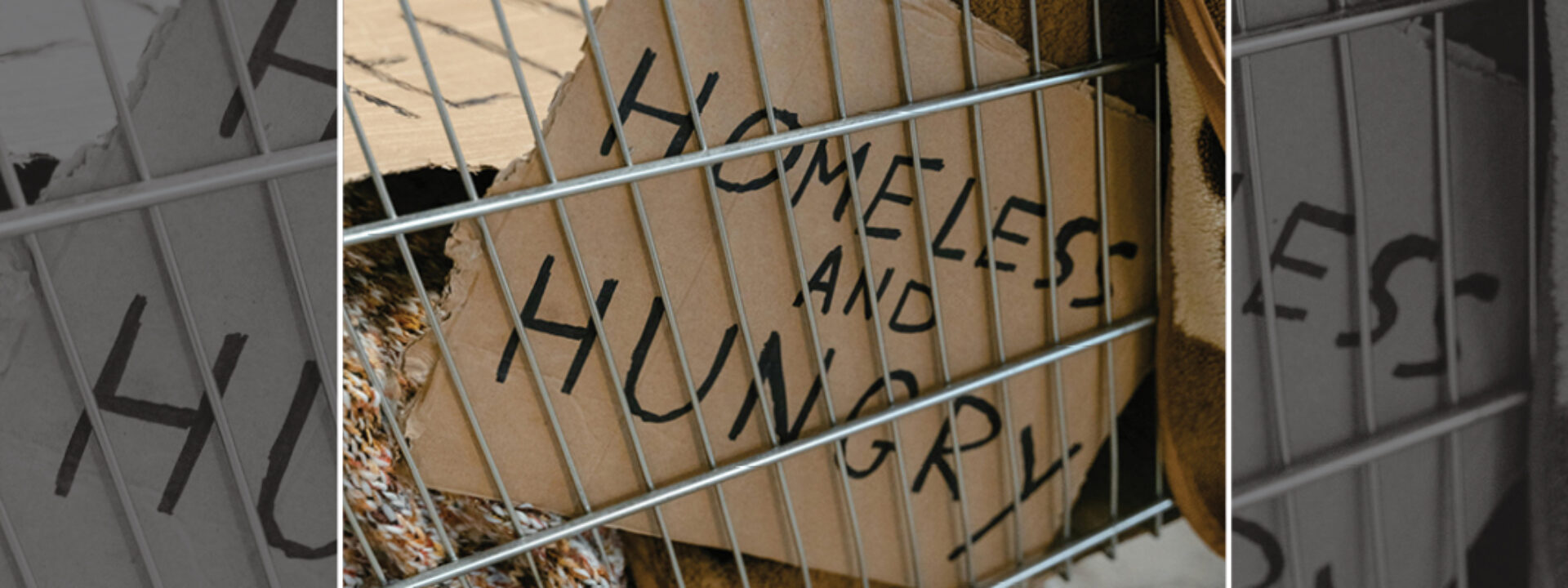

Photos: Jack Soule/Human Beings of Hamilton

I opened this essay with a reference to American politics because that country casts an outsized shadow across the world, and particularly in Canada, where American political tendencies tend to radiate across the border.

In addition to the sense of urgency around taking action, another trend in evidence at the DNC was the mainstreaming of what is sometimes called supply-side liberalism: the idea that an important way to ensure everyone has access to a public good is to produce more of it.

If you want, say, housing to be more available, it makes sense to build more housing. From a policy perspective, you can work backwards from the desired outcome, an increased supply of housing, to understand what the barriers are and act to clear them.

Amid the enthusiasm about Kamala Harris’ selection of Minnesota Governor Tim Walz as her running mate, a less-remarked detail of his political story is that when Minnesota passed a law mandating 100 per cent renewable energy statewide by 2040, state leaders recognized that the status quo regulatory framework would make this goal impossible.

So they also passed a comprehensive permitting reform bill that dramatically accelerates the approval process for new renewable energy projects. That’s right: liberals and progressives are coming around on the idea, long conservative-coded, that there is a need to cut red tape and bureaucracy, as long as it’s for socially beneficial projects.

Now that is an American idea I would love to see cross the border. Ontario cities like Hamilton are mired in decades-old zoning regulations that limit density and restrict mixed land use, combined with painfully slow and cumbersome permitting and approvals processes. Add in the ample opportunities for NIMBY opposition to infill development, and new projects can drag on for years before groundbreaking. Too often, the development proponent eventually just gives up.

The provincial government could fix the regulatory approval process in every city through changes to the legislation that governs municipalities, but aside from allowing up to three units per residential property as-of-right and encouraging higher densities along transit corridors, Premier Doug Ford’s primary focus has been on making it easier for developers to keep building single-family sprawl.