Vital Signs: A call to action on housing affordability

Homelessness is at crisis levels but there are plenty of solutions if we just have the political will to fight for them, Hamilton Community Foundation panel argues.

Homelessness is a choice, an affordable housing panel discussion hosted by the Hamilton Community Foundation heard on Wednesday.

But that choice isn’t being made by those living in tents in encampments or sleeping on the street, says Justin Marchand, CEO of Ontario Aboriginal Housing Services. It’s being made by policymakers and governments.

“Decisions are being made about who is important and who isn’t important.”

The Hamilton Community Foundation released an affordable housing report this week, the latest in its Vital Signs series.

“This is the first time we’ve taken a singular focus on an issue at crisis level proportions across the country,” said Terry Cooke, president and CEO of HCF in opening the evening’s well-attended discussion at the Hamilton Public Library’s central branch.

He said the housing crisis evident in small towns and big cities right across Canada has been a “slow-rolling catastrophe of abandonment by upper levels of government.”

An expert panel delivered a healthy dose of alarming reality when it comes to the dire state of affordability in housing in Hamilton but also some insights into the reasons for hope that exist.

Where homelessness at one time might have been about untreated addiction and mental health issues, it has now become an economic issue, said Steve Pomeroy, a Carleton University professor who is widely recognized as one of the leading housing policy experts in Canada.

Those with low incomes are “collateral damage in a dysfunctional housing system” in which many young people can’t afford to buy a house as that demographic has in the past, said Pomeroy.

The result is that they stay in rental units, which bumps out others.

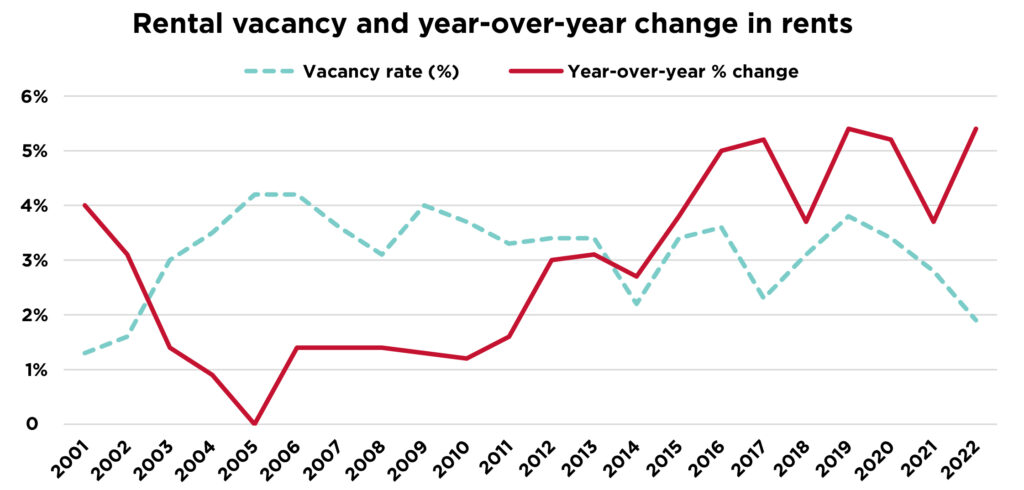

Hamilton has been particularly susceptible to rising house prices. Between 2020 and 2022, the city had the highest indexed rate of house price increase in the country. And that upward pressure has shifted to the rental market, too.

At the same time, Hamilton isn’t building as much rental housing as other cities. Just 1,200 units were completed in 2022, but they came on the market at a 44 per cent premium over average rents.

“What’s being built is not affordable," said Pomeroy.

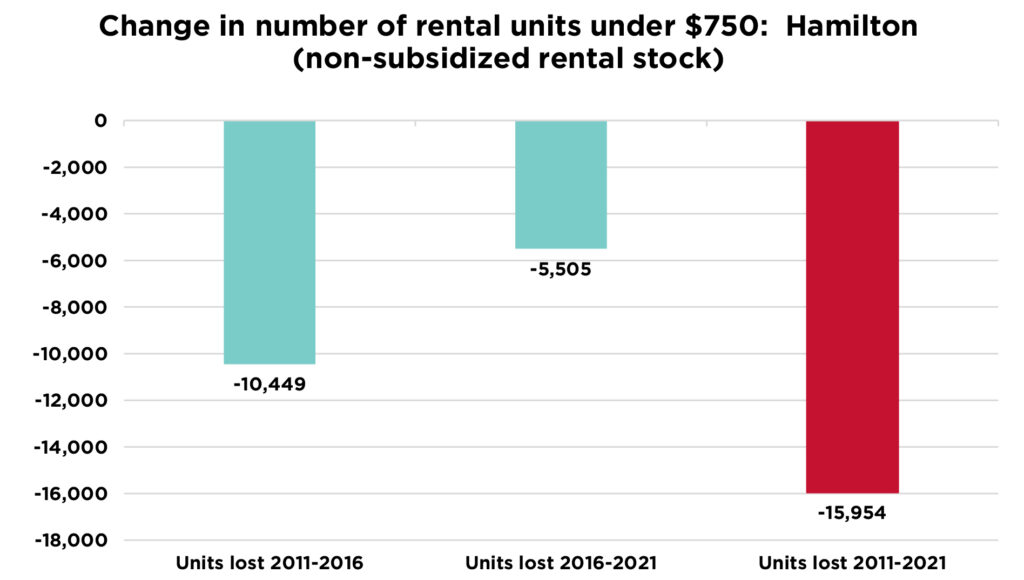

In fact, the city is losing ground on affordability in the private market, losing 23 affordable rental units for every one such unit built over the past decade.

Adding to the short supply, social assistance benefits have remained static while rents have soared. The average rent for a bachelor unit is now $900 while the rent allowance under Ontario Works or for those on disability supports is just $390, says Jeff Wingard, project manager of Vital Signs and a senior manager with the Greater Hamilton Health Network.

“And that average rent is for all units. When you account for only for actual available units, the average for a bachelor is $1,470 and $1,900 for a one-bedroom. The system is entirely wishful thinking and the reason for the rise in homelessness.”

And as migration into Hamilton has more than doubled to about 14,000 people a year since 2016, the housing shortage just gets worse.

But building more homes alone won’t influence affordability, says Pomeroy.

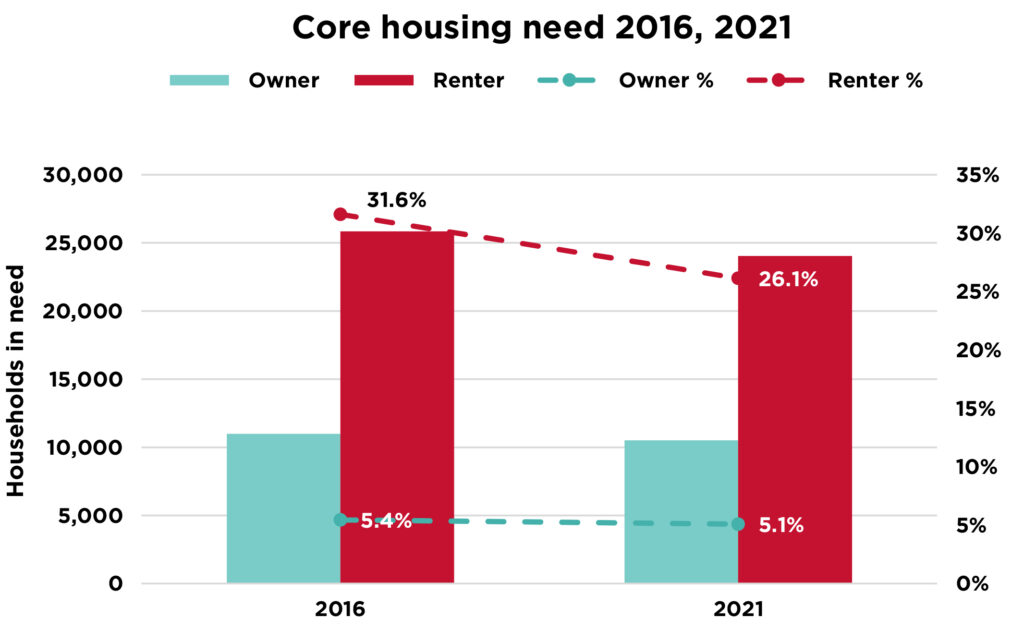

What it will take is a focus on incomes and the pandemic proved that to be true. In 2021, core housing need (which accounts for unaffordable, inadequate and overcrowded conditions) actually dropped in Hamilton. That was because of the influence of the Canadian Emergency Relief Benefit (CERB).

“That shows that there are solutions and it’s not just about housing but about income assistance and security and then training people for well-paying jobs,” said Pomeroy.

“Income assistance is housing assistance.”

Other policy solutions, he says, include limiting the rent increases property owners can impose when old tenants leave and new tenants arrive, requiring the replacement of any affordable units during the redevelopment of a property, and ensuring that displaced tenants have the right to return at the same rent.

Wingard says Hamilton’s non-profit sector has stepped up to provide 318 new supportive housing units since 2021 and 414 new rent-geared-to-income units. More are slated for 2024. As well, CityHousing Hamilton has renovated 476 rent-geared-to-income units that had been offline.

City policies allowing accessory units in dwellings (600 have come on the market so far), preventing so-called renovictions, and cracking down on short-term, Airbnb-style rentals will also have a positive effect, he says.

“There is a myth out there that the housing crisis is too massive, too complex and too costly to solve,” said Jeff Nevin, CEO of Indwell, which has built supportive, affordable housing for 1,111 tenants and has close to 700 more units under construction or in pre-development.

“The problem is finite. We know the names of the people in the tents. We are ready to go in Hamilton. The solutions are out there, but we need the federal and province governments to come forward, too.”

Hamilton’s light-rail transit project is a critical opportunity to ensure affordable housing is built along the corridor, says Brian Doucet, a University of Waterloo professor who holds a Canada Research Chair in Urban Change and Social Inclusion.

“Higher order rapid transit makes for more desirable and attractive neighbourhoods but that has meant more expensive and more exclusive.”

Hamilton must learn from Waterloo and not just build LRT and let the market dictate development around it. He pointed to the example of Burnaby, B.C. which requires that the makeup of every development be at least 20 per cent affordable. It has also enacted strong protections for tenants displaced by new developments.

Cooke said Hamilton has already faltered by selling the former Delta high school property to a private developer for $15 million. The Hamilton Community Foundation had backed a $4.75 million proposal from Indwell that matched market value.

“That property is on the transit corridor. We can’t make that mistake again.”

But there are people stepping forward to help, says Cooke, including a local faith group that is offering a redundant church to a non-profit housing provider for 50 per cent of market value.

Marchand pointed out that 22 per cent of those experiencing homelessness are Indigenous, while making up only 2 per cent of the population. He said the City of Hamilton is the only municipality in Canada that has allocated 20 per cent of its homelessness services budget directly to a coalition of Indigenous non-profits to use as they see fit.

A man in the audience who identified himself as a low-income resident of a rental property on Main Street East that went without water for nearly three months says he “sees things from the bottom up. The Landlord and Tenant Board has turned into an eviction factory that operates with very little compassion.”

Marchand responded that his organization is always looking to buy rental properties.

“Our motivation is to look after tenants, not make money.”

All the panellists urged the audience to turn up the heat on politicians at all levels of government and demand that the federal government return to funding social housing.

“One-third of us are renters and that’s a huge constituency,” said Pomeroy. “What we need is a renters’ revolt in this country.”

It’s about changing public mindsets, too, says Cooke. When neighbours fight affordable housing developments because they will change the area’s character or bring “undesirables,” local politicians must have the courage to stay the course.

HCF has promised to release its comprehensive affordable housing strategy this winter – a 10-year, $50 million commitment called SCAFFOLD: Supporting Affordable Housing Efforts.

So far, HCF has funded supportive housing and affordable home ownership programs, advocated for policy changes, supported property acquisition and preservation for affordable housing, and funded and shared research.

The foundation, which manages assets of $250 million, has partnered with non-profit supportive housing providers including Indwell, Hamilton East Kiwanis and Sacajawea.

Mayor Andrea Horwath had been scheduled to kick off the evening with an interview about various aspects of the housing situation, including the Greenbelt and the urban boundary, housing policy, encampments and the tiny homes debate. But she tested positive for COVID on the weekend. She’s committed to a future event, Cooke said.